When you come back from an injury or surgery, you have a few options: resting the area, avoiding movements that cause pain or taking certain medications to ease discomfort. But what happens when you’re in pain for months — even years — after the area has healed?

Researchers at Brown’s Carney Institute for Brain Science developed SOMA, an app that allows users to track and monitor pain to better understand chronic pain and eventually help create intervention tactics.

The team aims to build a platform that immediately helps patients and researches better treatments, said Frederike Petzschner, assistant professor of psychiatry and human behavior and director of the Carney Brainstorm Program. “Because, right now, chronic pain is very hard to treat.”

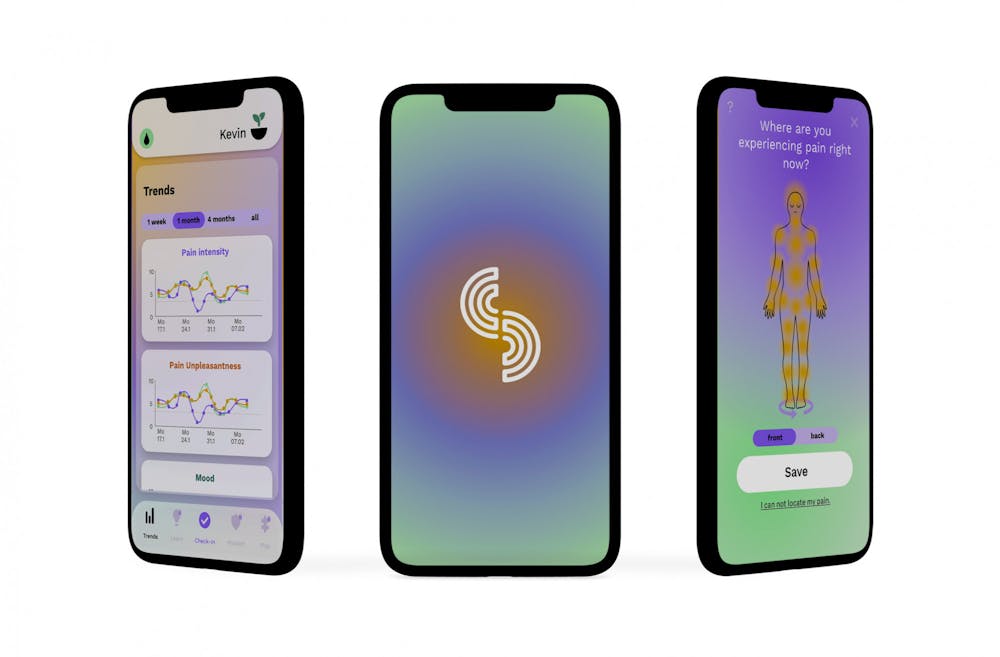

The team behind SOMA plans to release the app in late October, according to Petzschner. It will include daily and nightly check-ins for users, which will ask them about their mood, their activities from the day, how pain interfered with their day and if they took any intervention measures such as medication.

An additional screen will eventually show users trends across past weeks and months, aggregating their personal data on the frequency that they experienced pain and how the pain has affected their mood and activities, Petzschner added.

The second release of the app, scheduled for 2023, will focus on intervention measures, Petzschner said. It will provide patients with cognitive-behavioral approaches to treat pain that are informed by many existing therapies, such as breathing and attentional exercises. The second release aims to educate people about pain and the warning signs for it.

The team hopes to build new interventions based on user data collected following the first release of the app. Those interventions may combine various therapies in a more personalized approach to pain reduction.

Acute pain vs. chronic pain

One reason neuroscientists are interested in studying pain is because of the elusive mechanism of chronic pain.

There are entirely different brain areas involved in acute pain, which may occur after an injury or surgery, compared to chronic pain, which lasts at least three to six months after the tissue has healed. According to Petzschner, certain forms of chronic pain may be a form of “learned pain,” where the brain has learned a fear response over a continuous period of time, even in the absence of tissue damage once an injury has healed.

In other words, while acute pain may be thought of as a warning of existing or potential tissue damage, chronic pain may emerge from the continued aversion to certain movements that previously triggered pain during the original tissue damage.

“That gives us a hint that there are top-down processes that can cause pain, even if there's no signal coming from the body,” Petzschner said.

Chronic pain may also be partially linked to degeneration, such as in the back, knees and hips. According to Petzschner, over 50% of people over 30 experience disk degeneration in the back, yet only some experience chronic pain — perhaps a result of the brain misinterpreting or overreacting to signals coming from the body.

A multidisciplinary project

A team of scientists, clinicians, software engineers and designers started working on the project in February 2021.

The project embodies the tension between science and good user design, said Bradford Roarr, lead research software engineer at Brown’s Center for Computation and Visualization and lead software engineer for SOMA.

One challenge of the app is trying to temper the needs of research to facilitate the user experience and making compromises to reduce bias in user response, he added.

Initially, users were prompted to use a slider to indicate their pain on a range with a smiling face, neutral face and frowning face, Roarr said. The researchers brought up concerns that users would be primed to associate their pain with a smiling face, so, instead, the team replaced the faces with an orb of light that grows bigger or smaller depending on how much pain a user has — a more “value neutral” tool which still gives users visual feedback.

“It's not very technically different (from) building another app,” Roarr said. “What makes this app exciting is the domain that it's in — the fact that this is an application that aims to serve a population of people who are suffering. I think it’s a really cool, noble thing to do.”

Anonymized data from the app will be used for research to improve the prevention and treatment of chronic pain, said Petzschner. Some users may also track and log their pain in the app as a part of data collection for specific scientific studies outside of the SOMA project itself.

Petzschner said the team prioritizes user privacy — for users who do not want to participate in a specific research study, the app asks only for emails without any other identifying information. Data is stored on secure Brown servers to protect user privacy.

The app also allows other researchers access to the existing anonymous data upon request. “The idea is not just to do this for us — there's too much knowledge to be gained,” Petzschner said. She emphasized how users will “directly profit” from using the app, as researchers will be able to use data from a broad audience for further research.

During the first few months, Louis Rakovich, who graduated this year from RISD’s MFA program in design, worked with the team as a volunteer to design the visual aspects of the app — such as branding, layout and the logo — and to provide a visual framework for the app that could be expanded later in its development.

“It's an unexpected combination of disciplines,” Rakovich said, but “really, it's a combination that makes a lot of sense.”

“Ultimately, design and visual communication is all about perception,” Rakovich said. “How do we make sense of our world? How do we navigate our environment? How do we perceive the world around us? And to a large extent, that's also what SOMA is about — just the power of the brain to affect our physical sense of being.”

Haley Sandlow is a contributing editor covering science and research. She is a junior from Chicago, Illinois studying English and French.