On April 2, UNESCO confirmed damage to at least 53 Ukrainian cultural sites since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of the country on Feb. 24. In a statement released six days later, UNESCO Director-General Audrey Azoulay expressed the need to protect Ukrainian culture “as a testimony of the past but also as a vector of peace for the future.”

The Herald spoke with four Ukrainian and Ukrainian American artists based in the Northeast and overseas about their work and the invasion’s impact on their practices.

Anna Scherbyna — a Kyiv-based multidisciplinary artist — spoke to The Herald from Germany, having left Ukraine after the Russian invasion by crossing the Polish border. Despite her interest in contemporary art, her education in fine arts in Kyiv was classical. She recalled that “educational programs were quite strict” since they were developed during the Soviet era that promoted social attitudes of “making workers out of people.”

As a contemporary artist and cultural activist, Scherbyna finds the past “interesting,” specifically Ukraine’s historical connection with Russian imperialism, since Ukrainian society has only begun to “find a way to deal with the past” in recent years, she said.

Her most recent work, a multimedia installation titled “Where Did It Happen?” (2021), portrayed the destructive effects of war. Scherbyna collaborated with Austrian artist Christina Werver to address Babyn Yar, a Kyiv Holocaust site marking where Nazis murdered over 33,000 Ukrainian Jews. The historical site is one of the 53 cultural sites damaged by Russian attacks.

The project superimposes modern and archival images to interrogate the “potentiality of inhumane actors,” Scherbyna said. Reflecting on her political engagement, she added that “art is always political because it changes positions in space.”

In a video piece called “Untitled” (2013-2014), Scherbyna — who lived in Kyiv during the Euromaidan protests, which ousted Ukraine’s Kremlin-friendly government during late 2013 and early 2014 — filmed herself walking through the crowd, muttering “Glory to Ukraine, Glory to Heroes,” a chant that became popular during the Ukrainian War of Independence. Scherbyna recently rewatched the piece as she prepared it for a contemporary exhibition. She recalled difficulties finding her voice “there because the rhetoric became so nationalistic.” Thinking about the phrase “Glory to Ukraine, Glory to Heroes,” Scherbyna added, “the heroes are the victims. … Now this slogan is not so bad for me.”

Pavlo Grazhdanskij, a New York-based artist from Kharkiv, wrote in an email to The Herald that art involves “creating a space for dialogue.”

“I was living in Russia for a year already, and I watched (Euromaidan) through the screen in St. Petersburg,” Grazhdanskij wrote. “There is no freedom of speech in Russia, art is no exception,” he added, noting that his “work as an artist is to identify contradictions and change the attitude toward phenomena in the visual space.”

Since the annexation of Crimea in 2014, “this war has only strengthened the (Ukrainian) national identity and truly rallied people,” Grazhdanskij wrote, adding that a Ukrainian identity “includes representatives of various nations, as well as Russian-speaking people” and that “what unites them is the idea of a free country, the ability to be yourself at home.”

This sense of national pride is also shared by some Ukrainian American artists. Lesia Sochor, a Maine-based Ukrainian American artist, paid homage to her cultural heritage with a series of paintings depicting pysanky — hand-painted eggs which are a part of an ancient Ukrainian spring tradition. The pysanka “ensures good health, abundance, fertility, protection,” said Sochor, who grew up decorating the eggs with her mother and continues the tradition with her children. Dedicating a decade to exploring the egg’s historical symbology, Sochor sought to interpret the egg’s “allegorical magic” as a historical object with contemporary significance.

The purpose of her artwork ranges from cultural expression to a “political vent,” Sochor said. Sochor’s three-piece painting series, “Babushka” — part of her current installation at the Museum of Russian Icons in Clinton, Mass. — was created in response first to Euromaidan, then to the Russian invasion. The third and most recent piece, “Freedom,” created in response to the invasion, depicts a white babushka as “a symbol of peace.” Within the blank, faceless oval, Sochor wrote “freedom” in the Ukrainian Cyrillic alphabet.

Born to parents who fled Ukraine during World War II, Sochor recalled that she was always told there is a “definite separation” between being Ukrainian and Russian. “Even though there are similarities,” Sochor said, “the distinctions are profound.” The two nations each have their own alphabet, language and cultural traditions, she added.

Sochor decided to incorporate the pysanka into her paintings — eventually completing the series, “Pysanka: Symbol of Renewal,” which was re-staged at the Museum of Russian Icons after the invasion began. This creative expression helped create a “huge connection to my roots, my ancestors,” Sochor said.

Ilona Sochynsky, another Ukrainian American artist and a RISD alum, also highlighted the importance of her Ukrainian cultural heritage.

“As a first-generation Ukrainian American, I treasure my Ukrainian cultural heritage, but I also very much identify as an American, having absorbed this culture as well,” Sochynsky wrote in an email to The Herald.

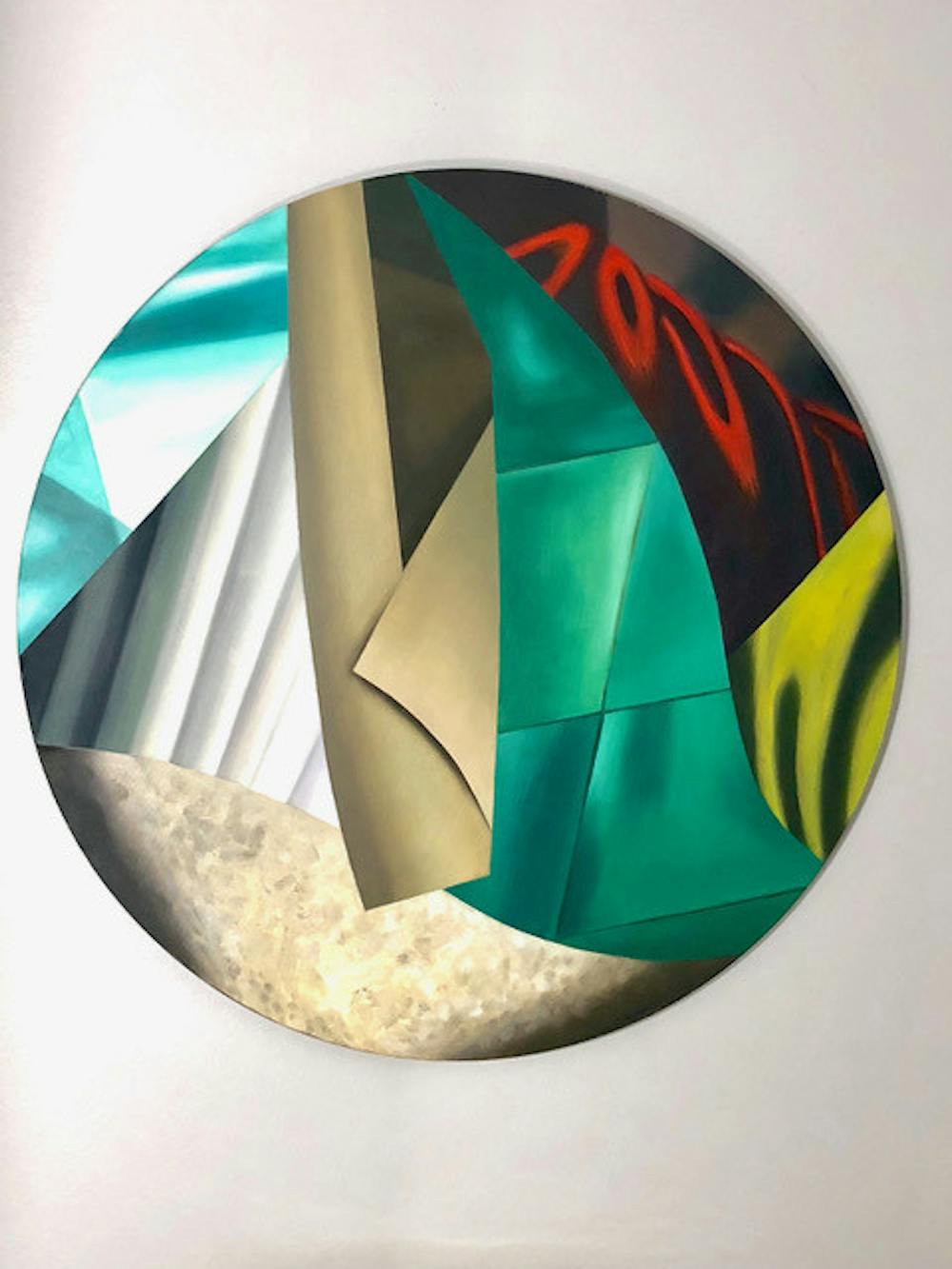

Her recent exhibition “Etudes, Fugues, and Impromptus” (2021) at the Ukrainian Institute of America in New York City chronicles a career-long journey from hyperrealism into abstraction. She emphasized the importance of institutions like the Ukrainian Institute of America, adding that they have succeeded in “sharing Ukrainian culture and heritage” in the United States.

“I am grateful that they are alive and well and that I have been invited to participate in their art programs,” she added.

Other than emphasizing the importance of their Ukrainian identity in their work, artists who spoke to The Herald also touched upon the influence of oligarchs in the art sphere. In 2020, the PinchukArtCentre — a contemporary art institute in Kyiv founded by Ukrainian oligarch Victor Pinchuk — nominated Scherbyna and Grazhdanskij for its prize.

Scherbyna said that Ukrainian oligarchs have “influence on the government and state.” And Grazhdanskij — who withdrew from the competition in response to Pinchuk’s dismissal of 30 guides and mediators after they formed a trade union — said the “large number of artists who remained silent … who participated in Pinchuk’s awards and exhibitions, who received awards and media attention and did not say even a word” reflects the influence of oligarchs.

Artists who spoke to The Herald also discussed how the invasion has complicated national identity. Because Scherbyna also engages with feminist optics and feminism, she stressed the need to maintain “solidarity with Russian feminists” despite the disruptions caused by the war, though she emphasized that she understands the frustrations of Ukrainians about the Russian people.

Thinking about the future of Ukraine, Grazhdankij pondered: “What will be the space for public dialogue in post-war Ukraine?”