Last week, Robert Britto ate at Chomp Kitchen and Drinks on Ives Street with his wife and kids.

Britto, currently a city councilman in East Providence, was born and raised in Fox Point. As he sat across from his children in the trendy burger restaurant — which filled the space once occupied by Portuguese-owned Eagle Super Market in June 2020 — he shared his memories of the Fox Point he grew up in.

In Fox Point, “the older generation never knew how to drive,” Britto explained. Everything residents needed — grocery stores, restaurants, community centers and employment — was within walking distance.

Britto said “it was nice to see that they still had … the Eagles Market” sign when he ate at Chomp, as well as other remnants of the neighborhood that once was.

“Look on their back wall (in Chomp),” Britto said. “They got these little plaques with names on it,” commemorating some of the former Fox Point businesses — one was Melay’s Pub owned by Charlie “Melay” Simon, he added.

Simon spoke to The Herald in 1989 about how the Fox Point community had changed since his days running Melay’s Pub in the 50s. “It used to take him hours to walk across … Fox Point because he would stop to say hello to all his neighbors,” The Herald reported.

The neighborhood was already changing in the late 80s. “Most of his old friends have moved out,” the article continued. “Now he can walk across the neighborhood in five minutes.”

“I don’t think I’ll live to see it, but eventually this will be a Brown community,” Simon said. “We’re going to lose our ethnic neighborhoods.”

“I don’t think that sometimes students realize the implications of them moving into the neighborhood,” said Ward 1 Councilman John Goncalves ’13 MA’15. “A lot of these people have already largely been displaced, so it’s hard to see that.”

Simon passed away in 2012, and today his neighborhood only bears hints of the community that used to be there.

During the 20th century, Fox Point was a community of immigrants — Cape Verdean, Portuguese, Irish, Lebanese and more. But, in the latter half of the century, those residents were displaced by the impacts of urban renewal, the expansion of Brown University, students living off campus and gentrification.

“Everyone knew one another back then”: The Fox Point community in the 20th century

Britto's grandfather left the Cape Verde Islands in the early 1900s and arrived on the Ernestina, a Cape Verdean boat, in India Point Park. He became a longshoreman and "settled down in a small place called Fox Point," Britto said.

Cape Verdeans were among the first Africans to willingly come to America on their own ships, according to the documentary “‘Some Kind Of Funny Porto Rican?:’ A Cape Verdean American Story” by Emerson College professor, filmmaker and historian Claire Andrade-Watkins.

Fox Point was often the initial point of contact for people immigrating to Rhode Island, said Kate Wells, a curator of the Rhode Island Collections at the Providence Public Library.

“My mother and father came to this country 95 years ago into Fox Point,” said John Murphy, who grew up in Fox Point and was its city council representative from 1966-1975. Murphy remembered Fox Point as a tight-knit and integrated community.

The Boys Club, now the Fox Point Boys & Girls Club, was a focal point for the community, according to Murphy. In the early 20th century, boys — including Murphy, Simon and Britto — would go there to play sports, shower and socialize.

“The Boys Club was a big education for me. I was there since I was five years old,” Murphy said. “It was fifty-fifty white and Black Cape Verdeans. (We) had a good rapport. We (were) all poor,” he explained. Frequently, Fox Pointers of different ethnicities made contact and became friends, he added.

There was “the integration of Black and white kids during the 40s and 50s, intermingling with one another,” at the Boys Club and beyond in Fox Point, Britto added.

John Britto, Robert Britto’s father, worked at the center for 60 years, where he was in charge of the gym and coached basketball and soccer. Robert worked alongside his father as the organization's director for a decade.

John Britto was known as a pillar in the community and acted as a father figure to generations of Fox Pointers, the Providence Journal reported. He passed away in January 2021 at 87 years old.

“We just really enjoyed the life that we lived in Fox Point growing up,” Britto said. “We didn't have much. (But) we didn't realize we didn't have much.”

In addition to The Boys Club, several churches that offered services in Portuguese were central touch points for the community.

One such church is Sheldon Street Church, which was established in 1886 according to its website. From 1915-1938, the church was known as the “Portuguese Chapel” under its first pastor, Rev. Marian Jones. It still offers services in Portuguese today.

“Fox Point and its People: A Community Diary” was created by participants in a youth program in the summer of 1979 to document the history of Fox Point. The diary described Fernandes Bakery, Faria’s and Silver Star Bakery — the only one remaining today — as the go-to spots for pastries, sweet breads and other baked goods. All the shops were Portuguese-owned at the time.

Fox Pointers also went to several bars to unwind after work, including Manny Almeida’s Ringside Lounge. In 1973, Fresh Fruit, a former Herald subsidiary, wrote an article describing the bar. “‘Manny’s is the bar in the Point,’ one regular patron stressed. ‘There’s one other cafe but that’s mostly for whites,’ a lifelong Fox Point resident interjected.”

The article described a man known as Pop, one of “the oldest residents of the Point,” who said that Manny’s went “back to the moonshine days,” referring to the era of prohibition in the 1920s.

“A lot of the local people used to go (to Manny’s), and some Brown students would go there as well,” Britto said.

Within the tight-knit and diverse Fox Point community, neighbors cared about one another, Britto added. “Everyone knew one another back then.”

“A total nightmare”: Urban renewal in Fox Point

By the late 1950s, urban renewal and a plan to extend the I-195 highway threatened to alter the fabric of the Fox Point neighborhood.

“It was a total nightmare,” Murphy said.

According to the Providence Redevelopment Agency’s 1966 report on the East Side renewal project — which originated with the 1959 College Hill Study — Fox Point was designated as a slum or a “blighted area.” Characteristics of blight included “dilapidation,” “defective design” and “mixed character.”

These terms were used by the PRA to label the community, and did not reflect Fox Pointers’ sense of identity, Murphy explained. “They (were) good people,” he said. “There (was) pride of ownership in this neighborhood — it (wasn’t) … a slum.”

These redevelopment projects included cutting Fox Point in half to make way for highway I-195, as well as the rehabilitation and demolition of some homes in the neighborhood. Previously Wells explained, businesses had lined a four-lane road. “It was a very vibrant commercial district,” she said. “When they build the highway, they take out the public transit, they take out the businesses (and) commercial ventures that are there.”

The highway caused a massive displacement of Fox Point residents, particularly lower-income residents and renters, according to Britto. The PRA “broke a lot of hearts,” Ramos said.

The PRA demolished two houses in Fox Point on Oct. 2, 1969, despite them both being allotted funds for rehabilitation earlier that day. “At the time of the demolition, the (PRA) planned to construct tennis courts on the site instead,” The Herald previously reported.

“We don't play tennis in Fox Point!” Murphy said. “We play baseball, football and basketball.”

The Alves’, a longtime Fox Point family, saw impacts of urban renewal firsthand when their home on Pike Street was slated for demolition.

“About 75 years ago, Maria Rosalina and Antonio Alves, a young Cape Verdean couple, moved a few blocks from Link Street to Pike Street, where they raised their 16 children,” The Herald reported April 3, 1998.

Neighbors knew Maria and Antonio as Mamai and Papai, respectively, and their home was open to anyone in the community who needed it. Their daughter Dotty Ramos told The Herald in 1998 that 88 Pike Street “was a home not only for my sisters and brothers, but also for other people, like people whose parents were strict with them or who didn’t get along. They would come here and my mother and father always had a room upstairs for them.”

The PRA designated Pike Street as a slum area and informed families that lived there that they must move. “Maria said that the only way they would get her out of her house was in a coffin,” The Herald previously reported. And her persistence worked — she was allowed to stay.

Maria was offered $6000 for her home, Murphy said. “She kept it, she fought them, I kept her there. And when she died, her kids sold it for $200,000.”

In 1998, Pike Street was renamed Alves Way to honor the legacy of the family. “By this renaming, we honor all those of Cape Verdean background that live in, or in the past have lived in, the Fox Point area,” said former City Councilman Robert Clarkin, The Herald previously reported.

“The Providence Redevelopment Agency built nothing on the sites of the houses that they tore down — most of the properties are now rarely used parking lots. But the Alves’ house remained,” The Herald article continued.

It stood until ten years later. In 2008, 88 Alves Way was demolished to make way for a parking lot.

Urban renewal disrupted “the Cape Verdean diaspora that had a multigenerational footprint here,” said Fox Point Neighborhood Association President Nick Cicchitelli. “It’s a historical injustice.”

Brown’s influence and gentrification

Along with the impact of urban renewal, the University expanded southward and an increasing number of students were gentrifying the neighborhood, The Herald previously reported. “The Cape Verdeans were trapped by Brown University on one side and I-195 on the other,” Goncalves said.

The University had discouraged students from renting in Fox Point beginning in 1970, citing that student rentals often drove up prices in the neighborhood.

“I passed (a) zoning ordinance in 1972 that no more than three unrelated people could live together in one apartment,” Murphy said. “I didn't want Brown (students) coming down anymore.”

“When you had this influx of college students, and the University expanding, it kind of took away from that community as a whole. And there was, you know, a lot of resentment towards that,” said Britto.

But, by the 1990s, the studentification — student driven gentrification — of Fox Point had already played out. In 1989 The Herald reported that “since 1976, the average price for a single family home on Fox Point rose from $18,000 to $174,000, while the average cost of a multi-family home jumped from $19,000 to $162,000.”

“So it was slowly but surely gentrifying to the point that before you knew it, half the people were out of Fox Point,” Britto said. “And the new people coming in will look at you like you're the outsider.”

The Irish population, Murphy added, “is dwindling now.” The Irish church in Fox Point was sold, he said, “because there's no more Irish — it's all gone. They moved to the suburbs like me.”

In 1996, local landlords pushed the University to stop discouraging students from living in Fox Point. “Fox Point has changed significantly since then, as the native Cape Verdean and Portuguese populations dwindle, local landlords are asking Brown to reconsider its decision to not allow students to live there,” The Herald reported. Since then, the University stopped recommending students avoid renting in Fox Point.

Today, most of the Cape Verdean and Portuguese residents that lived in Fox Point have relocated to East Providence or other neighborhoods in Rhode Island.

Remembering what was and looking ahead

Though many of the former residents of Fox Point have been displaced over time due to gentrification and urban redevelopment, the vibrant history of the neighborhood has lived on through collected histories, Wells explained.

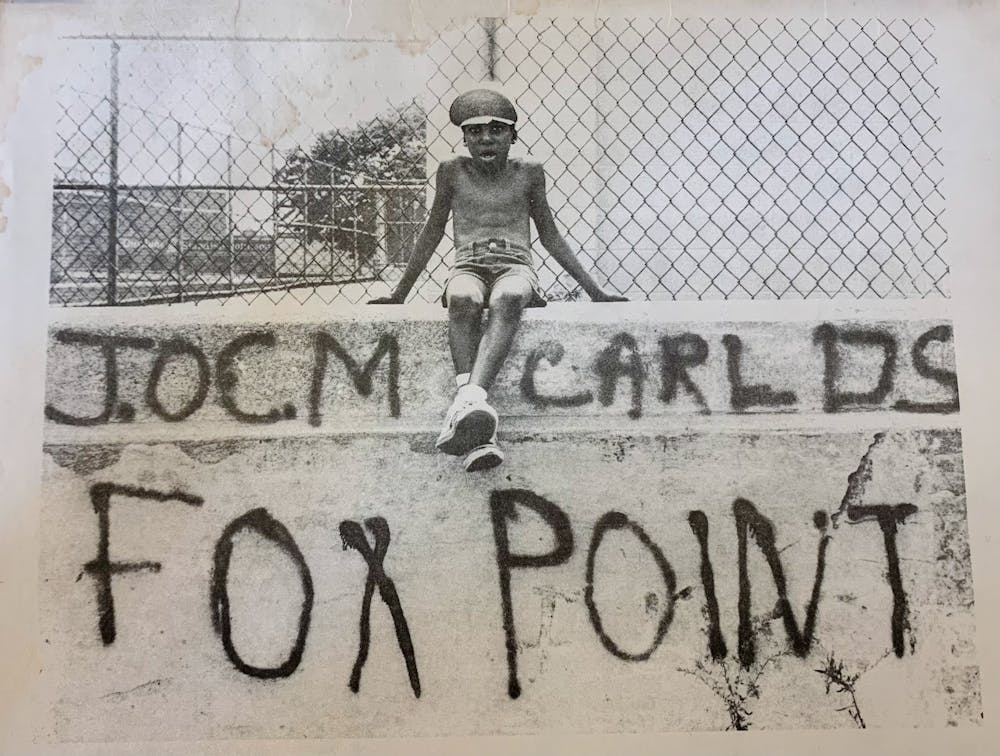

One of these histories was collected by Lou Costa, a local historian who worked for years to collect materials and photographs of life in Fox Point.

“Lou had been compiling it on his own for years — he basically just had a total love of the neighborhood he grew up in,” said Wells. “As his generation of friends started to get older and started to pass away, he got really worried that the community history would get dispersed, and nobody would know how to find it.”

Wells helped Costa to create a collection of these materials at the Providence Public Library. “He said, ‘it's a neighborhood collection, it needs to be really accessible,’ which is why he chose a public library,” she explained. “We worked with him over the course of about four years from the time he started thinking about donating.” The photographs and materials can also be accessed on the Fox Point Photo History Flickr.

The Fox Point Cape Verdean Heritage Place is currently creating another collected history which works to capture the history of Cape Verdean Fox Pointers and tell the stories of those residents.

“If we don’t preserve that history, it just perpetuates this notion” that there wasn’t “something vibrant in the (Fox Point) community” before students arrived, when, in fact, there was, Goncalves said.

“Certainly it’s a conversation that needs to be brought further into the light,” Cicchitelli said. The FPNA participated in the conversation of how to better respect and acknowledge the history of the Cape Verdean community in Fox Point, but “that conversation, as far as I know, is stalled,” he added. “It’s an open item … and FPNA is interested in finding a solution that works for everyone.”

The ongoing construction, renovation and housing replacement projects are “going to continue,” Cicchitelli said. Universities are also here to stay, and this economic engine “is a part of our community, and it’s a welcome part, as long as it’s kept in some appropriate check,” he said.

The FPNA also tries “to keep an eye on what private developers are doing,” including trying to protect building materials, neighborhood architecture and more, Cicchitelli added.“I look forward to what comes up,” he said.

But, the previous Fox Pointers have mostly left the area. Britto explained that he bought his first house in East Providence in 2001. While canvassing for his RI House of Representatives campaign in 2012, he knocked on each door in his neighborhood.

“I started recognizing people that I grew up with in Fox Point that I hadn't seen in years,” Britto said. “I would knock on this door — unbeknownst to me who that person was — and it was someone that I not only knew, but I grew up with.”

“In Fox Point you would see them all the time,” Britto said, “whether we are going to a convenience store, whether we are going to a Boys and Girls Club, whether you're going to a supermarket or you're having to pick up some bread and milk.”

“But here I am living, some two, three blocks away from somebody who I haven't seen in 15 years. And still the only reason why I saw him is because I'm running for office,” he added.

Still, “the magnitude of the community that we had” persists today, Britto explained. “We all grew up with one another … (even if) I don't have to see someone for 20 years, we’re picking up from where we left off.”

“I'm referencing my friends in the community as a whole,” Britto said. “We were such a close-knit community.”

Additional reporting by Rhea Rasquinha

Katy Pickens was the managing editor of newsroom and vice president of The Brown Daily Herald's 133rd Editorial Board. She previously served as a Metro section editor covering College Hill, Fox Point and the Jewelry District, housing & campus footprint and activism, all while maintaining a passion for knitting tiny hats.