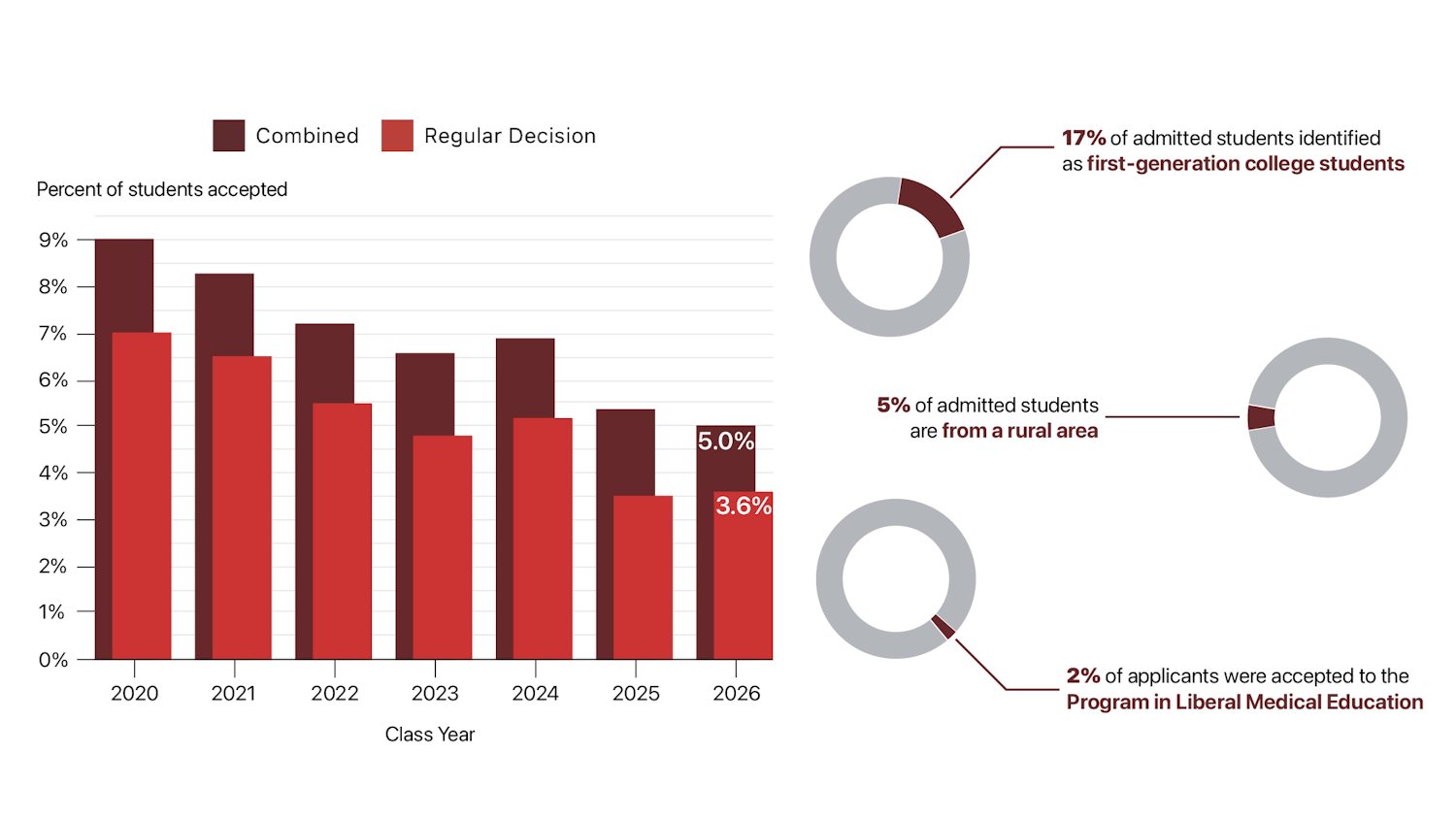

Spring is here, and with it, crocus buds, blustering winds and college decisions from schools across the country. Brown offered admission to a mere 3.6% of its regular decision applicants and 5% of applicants overall for the class of 2026. Applications were at an all-time high this year, breaking the record set the year before. Thinking back to my own application process, I’m reminded of the one phrase I saw again and again, in rejection and acceptance letters alike: “This was the most competitive year ever.” It was meant to soothe me when I did not gain entry to a particular school or to boost my ego when I did. But there’s something deeper, and more concerning, about the sentiment.

This kind of language, and the language we use to talk about college admissions and success in college more broadly, centers on competition and exclusivity. The value of enrolling at a school like Brown isn’t just based on tangible academic, social and professional opportunities, but also on how many others do not have access to those same resources. Comparing percentages and rankings turns education into a competition, leading us to revel in creating hierarchies and commodifying what is meant to be an experience. Selectivity should not be a point of pride but rather a sign of failure — the failure of a culture of higher education that prioritizes prestige over what a school can offer.

In recent years, there has been much talk about a so-called crisis in higher education. There are a swelling number of college applications — an increase of over 150% over the past two decades — and a slowly growing number of seats at selective institutions across the country. COVID-19 exacerbated this trend dramatically: With college tours canceled and standardized tests made optional, applicant pools increased across the board. There were 9% more applications to Brown this year than in 2020, which saw 27% more applications than 2019. Applying to college seems increasingly like playing a game of musical chairs with more and more players vying for the same spots when the music stops. But this perception could not be further from the truth. As Professor of Practice at Arizona State University Jeffrey Selingo notes, “selectivity is something of an illusion.” It’s true that applications to the “most selective colleges” in the U.S. have increased by 25% in the past two years and freshman classes have seldom expanded to accommodate them. But there are not five or fifty, but hundreds of colleges across the country that, like Brown, boast high quality academics, an abundance of community resources and dedicated faculty.

Yet, these schools are seen by many applicants as less desirable. What sets so-called “elite” colleges apart in the cultural imagination is eliteness itself. Prestige has less to do with the college experience or a student’s personal fit and more to do with selective admissions and post-graduation status — and its importance is only growing. The proportion of students who perceive a college’s reputation as “very important” when choosing a school has reached record highs in the past few years, according to surveys from UCLA’s Higher Education Research Institute. But selectivity and prestige have little relation to any given school’s opportunities for learning and self-actualization. Rather, they speak to an image of success based on hierarchy and exclusion of others. And what’s worrying is that schools may tend to embrace this mindset. Inside Higher Ed’s Jim Jump says, “At some point low admit rates changed from being a by-product of success to a metric of success and ultimately became the goal of the admissions process itself.”

Like many other selective colleges, Brown’s admissions have become steadily more competitive over time. In just 10 years, the University’s overall acceptance rate dropped from 13.71% in 2012 to the 5% we saw this spring. In an interview with The Herald, Dean of Admission Logan Powell noted that, “the difficult position of having to share bad news … gets more and more difficult each year.” Admissions officers, at Brown and elsewhere, may lament the difficulty of rejecting exceptional applicants, but by highlighting low acceptance rates in their own promotional material, they continue to reinforce their importance.

I know that after confirming my enrollment I was happy to never have to worry about personal statements or Common App activity descriptions ever again. And yet, a year later, I’ve come to realize that reflecting on admissions is important. The admissions process is where Brown practices its institutional values most meaningfully by actually creating its student body. In choosing not only who to accept but how to advertise and conduct its admissions, the school sends a message about its vision for how knowledge and power should be built, informed and exchanged. Brown’s commitment to academic exploration and “service to the public good” feels incompatible with a world where people believe the school on your degree determines your potential and overpowers the substance of your education.

Of course, despite all the issues that exist with the current system, college admissions cannot and should not not be a free-for-all. There will always simply be more applicants than spaces at Brown and there has to be some process to discern which students are a good fit for the school. Likewise, certain schools will always draw in more applications than others. But if we name extreme selectivity in admissions as a problem rather than a triumph, we can begin to conceptualize how to make the system feel more like an affirming choice for students rather than a scramble for the limited seats at top schools. The reframing of “highly selective” schools as “highly rejective” is one simple but powerful way of calling out the elitism in low acceptance rates as we work toward remedying it. The issue of rejectivity is deep, long-standing and will require measures such as expanding class sizes or reallocating resources to colleges that are looking to increase enrollment. But many of these conversations must also happen at the level of the individual university. At Brown, groups like Students for Educational Equity and new initiatives like the Student Admissions Oversight Committee can play a crucial role in influencing admissions policy and connecting administrative practices to the voices and values of the student body, rather than having admissions be built solely on competition.

Alissa Simon ’25 can be reached at alissa_simon@brown.edu. Please send responses to this opinion to letters@browndailyherald.com and op-eds to opinions@browndailyherald.com.