As the sound of the national anthem rang in the night session of the Gymnastics East Conference’s inaugural championship in March, three teams who had bounced onto the gym floor in monochromatic warm-up gear suddenly stood in silence, shifting nervously.

Brown, the fourth team present, sunk into a different posture beneath an American flag hanging on the gymnasium wall. Although a couple of gymnasts remained standing, most fixed one knee to the ground with their gaze pressed forward.

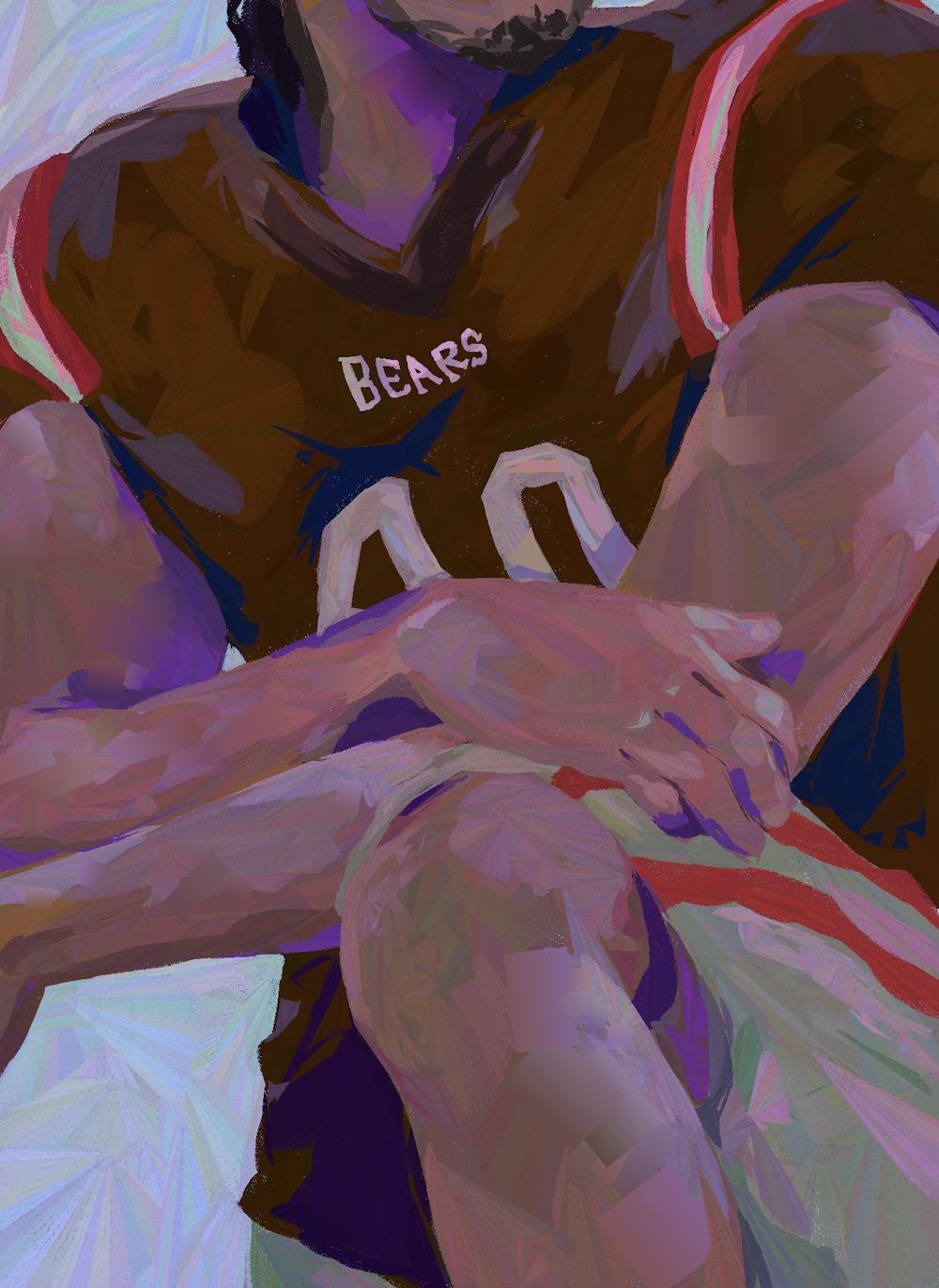

Repeated by the team throughout the 2021-22 season, the demonstration mirrored those of the women’s and men’s basketball teams, together marking one of the most visible efforts to protest racial injustice among Brown student-athletes since the murder of George Floyd in May 2020.

“It was really powerful to have that be the beginning of every meet,” said women’s gymnastics team co-captain Mei Li Costa ’22. “Usually you're sitting there very anxiously waiting for the meet to start,” but, during the protests, “you're taking that moment to really reflect upon that injustice.”

Co-captain of the men’s basketball team David Mitchell ’22 said he was one of five players on his team to sit for the anthem throughout the season. As a Black man, he “did not feel a connection to the anthem,” he explained. “The way I should be treated and the way everyone should be treated — (the anthem) wasn’t really coinciding with that.”

Grace Kirk ’24, one of the many members of the women’s basketball team who chose to kneel, cited similar motivations to Mitchell. “I have seen what America has done to people that look like me and people who are darker than me as well,” she said. “Who I am as a Black woman wasn’t … in (the writer of the anthem’s) visions for American patriotism, so I already know right then and there that it's not something that’s for me.”

Amid a national reckoning over racial injustice spurred by the police killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, protests like these have taken to a larger stage in Brown athletics, forming a fundamental part of student-athletes’ efforts to confront systemic racism, many athletes told The Herald.

All three teams hosted conversations over Zoom in summer 2020 to discuss issues related to racial inequality, with some assigning books and movies about racial identity in America to their athletes.

“We were late to talk about these things,” Costa said, mentioning that the gymnastics team focused its conversations particularly on how racial inequality plays a role in gymnastics.

Monique LeBlanc, head coach of women’s basketball, said her team made a spreadsheet of materials people could refer to in order to learn more about the Black Lives Matter movement and facilitate team-wide discussions. “The Black women on the team were phenomenal at sharing their experiences,” she said. “Our teammates stepping up and saying, ‘I’m exhausted, but I’m still willing to be here and share my story’… was really incredible.”

Kirk said that the team’s discussions were “a success,” particularly after she requested that players be allowed to have conversations without coaches present.

But Kirk noted that the discussions sometimes became contentious and the meetings eventually stopped.

Many players on the men’s team, in addition to holding conversations, also attended protests against police brutality in their hometowns during the summer of 2020, Mitchell said.

But because Ivy League athletic competitions were canceled during the 2020-21 academic year, it was not until a year and a half after the summer of 2020 that teams had the opportunity to protest during collegiate competition.

Mitchell said that he made the decision to kneel before the 2022 season. There were “so many instances (in 2020 and 2021) … that really opened my eyes to a lot of the racial injustice that was … not really right in front of me,” he said.

For Kirk, the decision to kneel was grounded in personal experience. In the summer of 2020, she heard her name being called from outside her family home in Minnesota as her father was held down and arrested by police officers, she said. She added that the officers charged him with a felony, but that the charge was eventually dropped after the family advocated for his release. “I was so traumatized,” she said.

“They say the system (that) tried to dismantle our foundation as a family did it in the name of justice,” she said. “If that’s what that flag stands for, I can’t support it.”

“When I see the flag and I’m supposed to stare at it for a minute or whatever before my game, … I see the police officer’s American flag on their uniform,” Kirk said. “I won’t stand for (the anthem), and I can’t because I feel like then I’m letting myself down, I’m letting my family down and I’m letting the millions and millions of people that came before me down by doing that.”

Kirk also questioned the necessity of standing for the anthem. “I don’t think a flag is the best method of expressing patriotism or gratitude for freedom,” she said. “I really think that you can do that without standing for a piece of material.”

Costa expressed a similar sentiment, explaining that kneeling adds valuable reflection to what she sees as a typically superficial moment. “The anthem is such a performative thing most of the time,” she said. “You’re not really thinking about how amazing America is.”

Kneeling, she added, instead “keeps (racial justice) at the forefront of your mind.”

But for all three teams, conversations about whether to kneel did not result in consensus. At least one player on each team remained standing for every game, according to Costa, Kirk and Mitchell.

Costa said that some of her teammates cited support for the U.S. military as a reason to stand for the anthem, although she maintained that the demonstration was “not meant as any disrespect to veterans.”

Gymnastics Head Coach Sarah Carver-Milne said the coaching staff encouraged gymnasts to make their own decisions. “The first thing we tell them when they get to campus is that they need to use their voice and advocate for themselves, for their beliefs,” she said.

The athletic department also encouraged “student-athletes, coaches and staff to use their platform and take a stance,” wrote Kelvin Queliz, associate director of athletics, strategic communications and content creation, in an email to The Herald.

Mitchell said the men’s basketball team similarly left the decision up to individual players. “We knew there’d be certain people who would stand (and) there’d be certain people who would sit, but we respected that fact,” he said.

Kirk described longer, more emotional conversations within the women’s basketball team about whether players would kneel. She said that before its first scrimmage, the team had a six hour meeting about their plans for the anthem.

“It actually turned into an opportunity for the nonwhite players to open up about their experiences,” she said. “There were tears.”

Kirk added that, after the meeting, a majority of the team decided to kneel.

Those who remained standing for the anthem explained their reasoning to the rest of the team, which was valuable, Kirk said. “In the moment it might have hurt a little more to hear so much negative feedback from a few people in particular, (but) at the end of the day, we all understood each other so much better,” she said. “It was a really, really powerful moment for us.”

But kneeling or sitting for the anthem was not the only way teams acted in support of racial justice.

Last November, the women’s basketball team visited the John Hope Settlement House in Providence, an organization founded in the late 1920s by African American community leaders to provide social services — such as child care, education and food distribution — to the Providence community.

According to Kirk, the team read books to the children at the facility, which she described as an “amazing” experience.

“A lot of my teammates were pushed outside their comfort zones … dealing with kids who aren't privileged, who are actually very severely in need of help and somebody to just come in and spend time with them,” she said.

LeBlanc said the team ran a book drive for the Settlement House after the visit, focusing on providing “culturally competent” books, and is making another visit this week.

LeBlanc added that the team also fundraised for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Legal Defense Fund and the Rhode Island Coalition for Black Women during the summer of 2020.

According to Mitchell, the men’s basketball team made efforts on social media to promote racial justice initiatives. For example, Mitchell mentioned that some team members made posts during Black History Month to highlight Black trailblazers throughout history.

Still, some athletes expressed regret that their programs have not done more. “There's definitely a lot more that we could have and should have done to keep those conversations going,” Costa said, adding that the gymnastics team did not follow through on plans to volunteer in the community, which she partially attributed to public health concerns.

Kirk also noted that the women’s basketball team could have been more “prepared and proactive” in promoting racial justice during Black History Month. “An Instagram post is not enough,” she said. “I wish we would have taken the opportunity to have more of those difficult conversations because I think everybody grew from that.”

In addition, Kirk noted that she would have liked to see more efforts from her team’s coaches to facilitate conversations and learning surrounding racial justice.

“I hope and wish and encourage my coaches to continue to do trainings and listen to talks,” she said. “If it’s just the Black players telling them, ‘Hey, this is how you have to coach me as a Black woman, this is how I feel on a regular basis walking through a (predominantly white institution),’ that’s not fair for us.”

Kirk, Mitchell and Costa all said that they expect their programs to continue with similar efforts to combat racial injustice in the future.

Our teammates “are all very attentive. They’re all very diligent,” Mitchell said. “They all know that we have the power and a platform both on this campus and in the city of Providence.”

“It’s not a phase, it’s not a trend,” Kirk said. “I think that us stopping would send a message (that) we’re over it.”

Kirk emphasized that for the Black players on the team, racial injustice is not something they can move on from.

“It never has died down,” she said. “It's never not on our minds.”