On campus and across the country, the federal government is directly involved in the funding of university operations. In 2020, the national government spent more than $205 billion on higher education, with the majority spent on student aid. The rest goes toward institutional priority ranging from research to tax benefits for students to the GI Bill, according to Terry Hartle, senior vice president of government relations and public affairs at the American Council on Education, an advocacy group for higher education.

This makes the federal government a crucial source of support for research and aid initiatives in higher education, Hartle said. It is also central to determining the immigration policies that dictate which international students, faculty and staff can come to American campuses. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, emergency legislation and pandemic response policies such as the CARES Act of 2020 and the American Rescue Plan of 2021 dispersed tens of billions of dollars into higher education.

While institutions of higher education lobby the federal government to influence these decisions, their lobbying looks different than most other types of political lobbying, Hartle said.

“Higher education does not lobby like anybody else you’ve ever heard of,” he explained. Colleges and universities are mostly tax exempt, their lobbyists do not hold political fundraisers, they do not do issue advertising and they cannot vote, he explained.

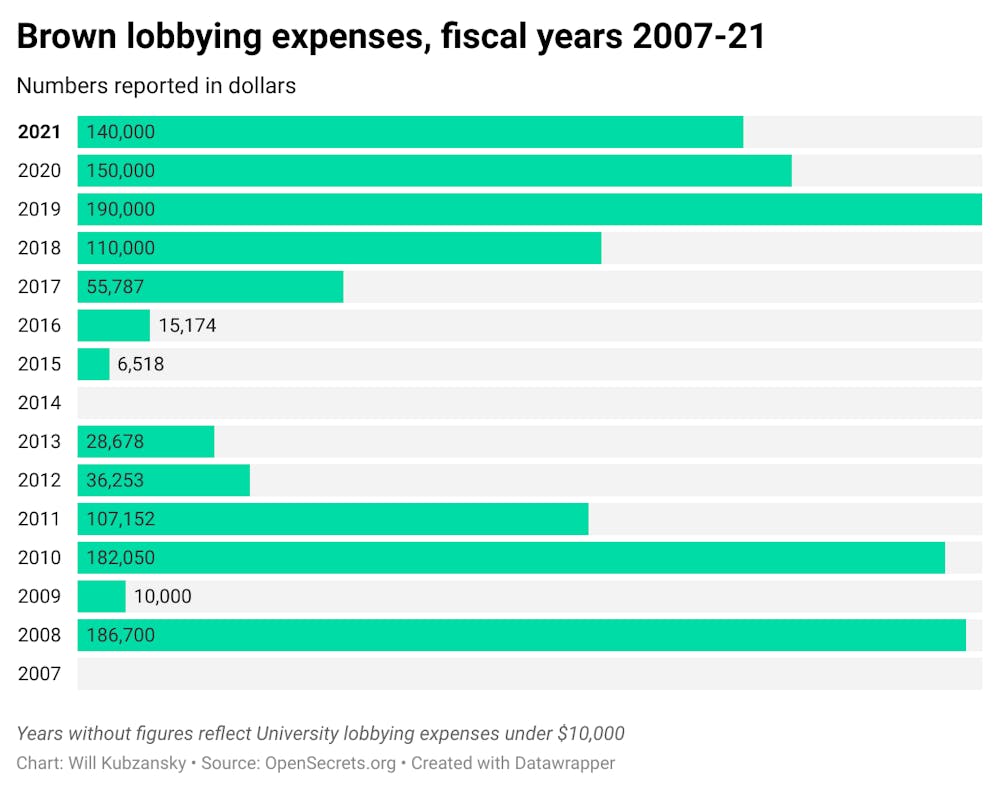

The University spent $140,000 on federal lobbying in 2021, down from $150,000 in 2020. The sum is the lowest among Ivy League schools with high enough levels of spending to require the reporting of federal lobbying expenditures, with Harvard and Yale leading at $560,000 each in 2021.

Universities "can genuinely talk about America’s national interest and long-term economic growth and social progress,” Hartle said — making higher education a less partisan issue than other topics for most policymakers.

Dartmouth does not report its federal lobbying expenses, an option available to schools that spend less than $13,000 per quarter.

Brown and its peers

For the past 15 years, Brown has spent less on lobbying than any other Ivy League school that reported its expenses, except for 2010, when Brown spent just under $30,000 more than Columbia. Dartmouth does not report its federal lobbying expenses, an option available to schools that spend less than $13,000 per quarter.

Transportation, food, lodging and dues to national associations are among “a variety of factors” that go into lobbying figures, according to University Director of Government Relations Steve Gerencser. “There’s always going to be some fluctuation, and there’s also going to be a rounding of the number.”

“Lobbying is not as simple as just telling legislators or their staff how we think they should vote on an issue,” said Al Dahlberg, the University’s assistant vice president of government and community relations. “It’s a much more nuanced process that usually involves sharing information, demonstrating why a certain policy is important to the University and our community and giving examples.”

The Office of Government and Community Relations at the University, which Dahlberg oversees, is responsible for lobbying the federal government, as well as state and local governments, on behalf of the University.

“Unlike some other schools, we don’t have a representative in Washington, D.C. from our office; neither do we have a lobbying firm that we hire in Washington, D.C.,” Dahlberg said. This means that a large portion of the lobbying not done directly by the office falls upon the associations to which the University belongs.

The associations

Rather than hiring lobbyists directly, many universities — including Brown — are members of mutual interest organizations. These groups, such as the Association of American Universities and the American Council on Education, work to facilitate communication and strategy building between various institutions of higher education on collective issues, Hartle said. These groups then lobby the federal government regarding those issues.

“The associations are very effective in sharing information, helping to develop relationships with colleagues, identifying issues early as they arise at either the legislative or regulatory level and … advocating on our priorities,” Dahlberg said.

Each institution pays membership dues to the associations they belong to, and an association like AAU will then spend a percentage of those dues on lobbying efforts, said Gerencser. Of the University’s reported lobbying expenses in a given year, a portion of the figure refers not to direct lobbying expenditures by Brown but to the sum drawn from dues paid to each organization in support of collective efforts.

“At the federal level, our associations track the amount they spend lobbying Congress and the executive branch,” Dahlberg said. “Then, they allocate (those expenses) to each member institution.”

Each year, for example, AAU informs the University how much it should report on their behalf, a number that varies based on travel expenses, the extent of lobbying and the issues at question, he added.

Unlike the University, some institutions, especially large public schools, employ the services of lobbying agencies or individual lobbyists based outside of their home state in addition to their association memberships, Dahlberg said.

While reasons to hire outside help vary, schools with large athletic programs concerned about name, image and likeness legislation or schools located in states with large populations and large congressional delegations may be more likely to seek additional services, he noted.

The University’s location in a small state like Rhode Island provides an opportunity to form personal relationships with the state’s congressional delegation that would not be possible in more populated states, he added. “We’re really lucky that we have the relationships and the access that we do.”

The issues

Despite the many factors at play, most colleges and universities share a common set of principles that determine associations’ legislative priorities, Hartle said. Among these, research, immigration and federal student financial aid are “evergreen.”

Considered by the AAU to be one of “America’s leading research universities,” Brown received $236.1 million in revenue from grants and contracts in fiscal year 2021, mostly from the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation and the Department of Defense, according to the University’s fiscal year 2021 financial report.

The AAU, which represents 66 universities in total, is an important advocate for the continued federal support that Brown and its peers receive for research, Dahlberg said. “Research funding is critical to Brown,” he noted. “It will always be a priority.”

Higher education institutions commonly lobby around visa and immigration policy as well, Hartle said. Visa advocacy focuses on issues ranging from the expansion of student and work visa access, while immigration advocacy tends to center around green card policy and the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program.

“We have always believed that it’s in America’s best interest to be the destination of choice for the world’s best students and scholars,” Hartle said.

Most institutions “support a positive policy toward DREAMers,” though not all have DREAMers in their student body, Hartle said. In 2017, President Christina Paxson P’19, Provost Richard Locke P’18 and Vice President for Campus Life Eric Estes called the Trump administration’s efforts to end DACA “shortsighted and in direct and flagrant conflict with this nation’s commitment to education,” The Herald previously reported.

The University’s visa and immigration priorities center on ensuring that students and faculty can come to the country, advocating for “well-thought-out policies,” and guaranteeing that visa agencies are appropriately staffed, according to Gerencser and Dahlberg.

“What we try to convey is how important DACA and immigration changes are to individual members of our community — the human element that’s at stake here,” Dahlberg said.

Federal student financial aid also makes the list of top lobbying priorities for nearly every institution of higher education in the United States, including Brown, according to Hartle. Through associations like the AAU and ACE, colleges and universities advocate for increased funding for federal grants like Pell Grants, which provide vital support to students with financial need on top of what the aid programs of individual institutions may offer.

“All colleges and universities, from the largest research university to the humblest community college, get federal student aid,” Hartle said. “So every institution will, at some point during the year, pay some attention to issues around Pell Grants and student loans.”

At Brown, students received over $5.6 million in need-based scholarships from the federal government in 2020-21, according to the University’s Common Data Set.

“Expansion of Pell Grants isn’t just confined to increasing the amount of the awards,” Dahlberg said. “It could also be expanded Pell eligibility, (or) allowing Pell to be used for summer study.” The University also worked with policymakers to streamline the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, in addition to other federally-funded institutional aid programs, according to Dahlberg.

The changes that came with the COVID-19 pandemic gave rise to a host of new programs that, in addition to temporarily providing for increases in student aid, also sought to address the challenges of remote learning. The University and AAU engaged in successful advocacy efforts regarding programs that impacted the legal delivery of remote content from outside the state it was created in as well as programs that eased the process of delivering health care across state lines, which ultimately was unsuccessful, Dahlberg said.

“There are so many important issues out there, and there’s only so much time on the congressional calendars,” Gerencser said. “Especially during a time of crisis like the pandemic.”

“When I talk to students or faculty about how we do our work, it’s much more nuanced than just saying, ‘We support this bill, we oppose that bill,’” Dahlberg said. “The earlier we can engage in that process of sharing information and feedback — and having a dialogue — the better a result you get at the end.”

Charlie Clynes was the managing editor of digital content on The Herald's 134th Editorial Board. Previously, he covered University Hall and the Graduate Labor Organization as a University News editor.