This article is part of a series on gentrification and development on the East Side of Providence.

The movement of people in and out of neighborhoods is a natural part of cities’ development. But an issue seen across Providence and the rest of the country is gentrification: the influx of new, often wealthier populations into an area in a way that negatively impacts its current members and the surrounding communities, often by increasing the costs of living and displacing residents.

The Herald spoke to a variety of housing experts about how gentrification has played out specifically on Providence’s East Side.

What is gentrification?

“Gentrification, as I understand it, involves re-envisioning neighborhoods to accommodate middle-class or upper-middle-class people at the expense of working-class and marginalized groups,” said Professor of Anthropology Patricia Rubertone.

Beyond land valuation in economic terms, there are also “related values that have more to do with how people dwell in different spaces … and the values that they attach to them,” because of experiences and family histories, Rubertone added.

According to Westfield State University Associate Professor Emerita of Geography and Regional Planning Marijoan Bull, who also previously taught at Brown, the issues of gentrification and displacement are interconnected. Gentrification generally occurs when a stimulus brings people of higher incomes into a neighborhood where people of lower incomes have lived, she said. There may or may not be displacement associated with this movement, Bull added.

Displacement can be physical, cultural and social — or a combination, Bull said. Physical displacement involves involuntary movement when individuals can no longer afford to stay in a neighborhood due to factors such as higher rent and property taxes. Cultural and social displacement is a result of services and businesses changing to cater to the new populations that move into a neighborhood, she said.

In some cases, the institutions that were serving the initial residents may find that, as displacement occurs, business slows down, Bull added. But “you can also have people still living in a neighborhood where they feel displaced culturally because the institutions or the businesses that served them are no longer there,” she said.

Another key issue specific to neighborhoods with institutions of higher education is “studentification,” which is similar to gentrification in that there is an influx of outsiders into communities — often communities of color — where a significant proportion of the population is low-income, but these outsiders are specifically university students, said Nathaniel Pettit ’20, whose senior thesis studied the history and displacement of communities on the East Side.

Landlords are often incentivized to take in students because they can often afford to pay more, he said. Additionally, several students can be housed in an apartment originally designed for one working-class family, Pettit added.

Another definition of gentrification describes the use of public-private partnerships and state-incentivized development in the private sector to construct newer and more expensive property in certain neighborhoods, according to Clinical Assistant Professor of Family Medicine and Adjunct Assistant Professor of Africana Studies Dannie Ritchie MPH’03, who teaches a course about Providence housing and gentrification. Black communities have been disproportionately impacted by these developments, fueled by a “narrative that Black Americans are undeserving of certain American staples of wealth and their possessions,” she said.

Factors at play in Providence

Just as gentrification can manifest in several different ways, there are many factors which influence why groups enter and leave a community, along with how the community is impacted, Bull said.

Urban renewal in the 1950s and 60s displaced residents of multiple communities in Providence, including Lippitt Hill, South Providence and Mashapaug Pond, Rubertone wrote in an email to The Herald. These types of urban renewal projects occurred early and often, she added, displacing populations from their ancestral homelands. “These are the traditional lands of the Narragansett tribal nation,” she said.

“Like many cities, Providence is very much a tale of two cities,” with East Side neighborhoods near Brown and RISD looking very different from the west side, said Brenda Clement, director of HousingWorksRI, a clearinghouse for information about housing policy at Roger Williams University.

According to the organization’s 2021 Housing Fact Book, 73% of Providence households cannot afford the region’s median home price of $275,000 and there are drastic differences in housing prices between the East Side and the rest of Providence. The East Side has more single-family homes, higher median household incomes and lower poverty and disability rates among households, according to the report.

Gentrification has contributed to this disparity as where people live impacts education, health outcomes, work prospects, pay and more, Clement said. “We knew well before COVID that zip code matters,” she said.

In Providence, a shortage of affordable housing is a major factor contributing to displacement and gentrification, according to Clement. Students moving off campus into rental units, in addition to an insufficient building rate, especially at the low-income housing level, increase competition and drive up prices, she said.

Before the pandemic, the rise of short-term rental services like Airbnb took properties off the market for long-term ownership and rental, and the pandemic has increased pressures from outside buyers, as people who are able to work from home have moved into the area, Clement said. Concern among community members about housing, especially for families seeking affordable units, was exacerbated by the pandemic, The Herald previously reported.

The Providence real estate market is also influenced by nearby cities, such as Boston and New York, according to Bull. As those markets become saturated, investors may look to cities like Providence for future development, potentially contributing to rising prices and the displacement of individuals who can no longer afford to stay, Bull said.

Beyond financial systems impacting housing, systemic racism also played a role, Ritchie said. She pointed out “long histories of (property) devaluation” for Black communities specifically. “I think they’re the most stigmatized. … Their property for decades has been valued less,” she said.

Additionally, Ritchie said Black communities have historically been denied generational wealth through housing policy. One method of wealth accumulation is through home ownership, but when people are “systematically denied” homes, “that’s stolen wealth,” she added.

Neighborhood impact from gentrification “is not one story,” according to Bull. Some people in a neighborhood that becomes gentrified may benefit from impacts such as higher prices when selling property, she said. “It’s difficult to untangle all the forces that are happening in a neighborhood at one time,” Bull added.

Another major impact of gentrification is the exacerbation of disparities around home ownership. Little to no progress has been made on homeownership rates for Black and other minority homeowners in Rhode Island and across the country since the 1960s, according to Clement. “We have literally slammed the doors shut now for several generations for Black and brown families,” with rates about half the rates of white families, she said.

Impact of Historic Preservation

Historical preservation has also played a role in how housing markets, development and displacement has occurred on the East Side of Providence.

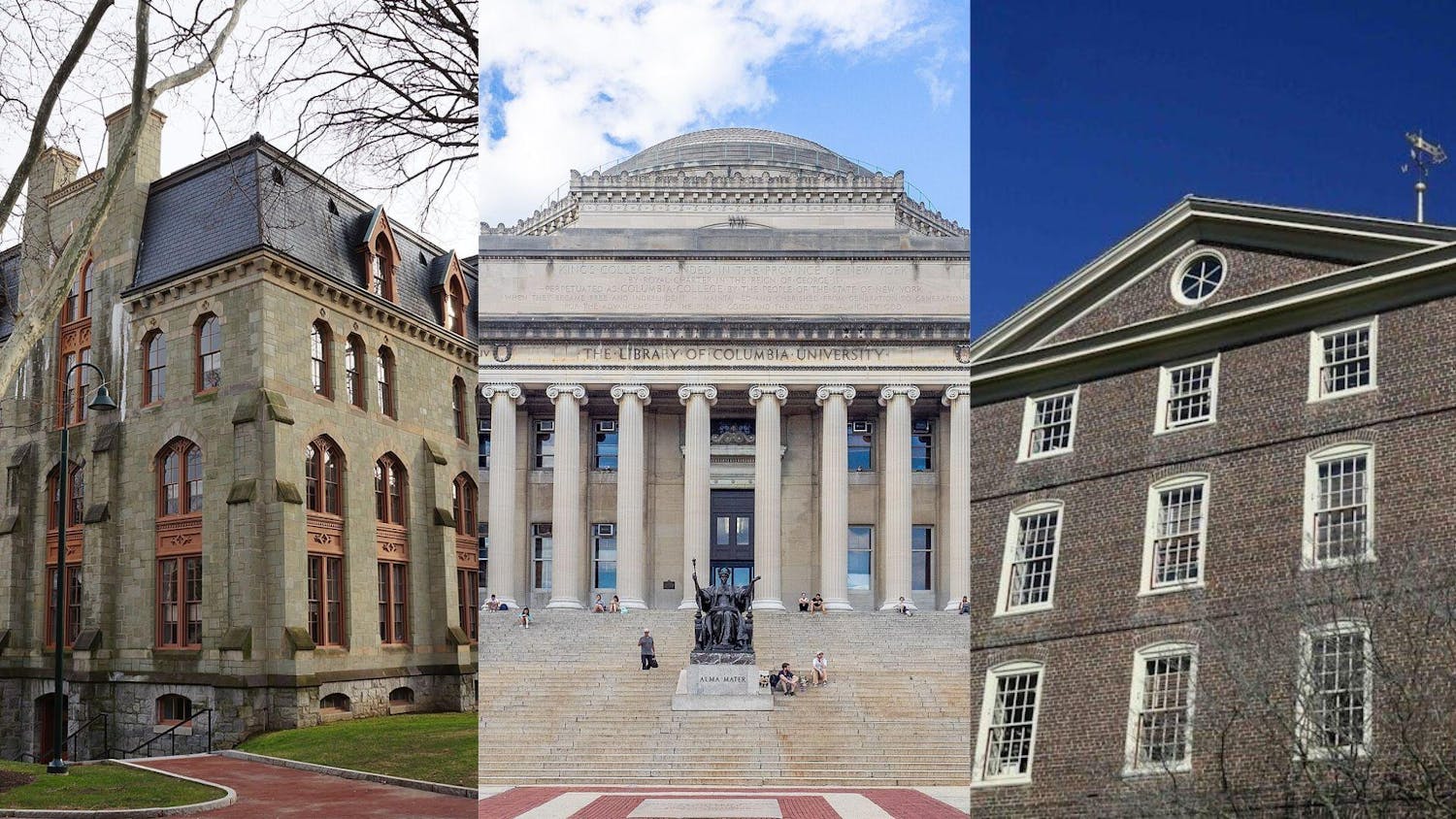

The Providence Preservation Society was established in 1956 in response to the University demolishing historic homes to construct dormitories.

But “they were unsuccessful at stopping Brown” from demolishing historic homes to build Keeney Quad, said Executive Director of PPS Brent Runyon.

“The people involved in forming PPS were people with long histories or family histories in this area,” Runyon said. He added that Antoinette Downing, wife of George E. Downing, chairman of the Art Department at the University from 1949 to 1963, was one of the individuals instrumental to PPS efforts and research.

Her work in preservation contributed to the restoration of approximately 750 homes between 1960 and 1980, according to a 1985 article in the New York Times.

Restoration of these buildings on the East Side had long-term implications and contributed to the displacement of non-white residents on and near College Hill, according to Pettit.

“Restoring Benefit Street, for instance, interwoven with urban renewal, resulted in gentrification and the displacement of longtime residents, many of them being residents of color,” Pettit said.

In 1959 and 1967, PPS published two editions of The College Hill Study, a survey of neighborhood buildings that pushed the idea that “historic preservation and all the historic architecture” in Providence can be part of urban renewal projects.

While PPS brought a fresh perspective to development that emphasized history, it was very inwardly focused on College Hill in its early years, Runyon said.

Historic preservation has at times been linked to gentrification and displacement because it can increase property values and housing payments, The Herald previously reported.

“If you're trying to preserve something or restore something, then it's very likely that you might need to increase the rent,” Runyon said. “Improvements will often mean displacement because the people who currently live there can't afford the new rent.”

Today, PPS works to be available to and “show interest in the people and historic architecture in all 25 neighborhoods of Providence,” said PPS Director of Preservation Rachel Robinson. PPS released a new strategic plan to “democratize preservation” last November, she added.

“It's really considering whose voices are heard in preservation and planning,” Runyon said. “What decisions are going to be made by having a broader set of voices at the table.” He added that PPS is striving to diversify their mostly-white staff, and that they are seeking to preserve more histories and buildings in marginalized communities.

Looking to the future

Though the issue of gentrification and its consequences have deeply historical roots, there are future policies and steps that institutions and communities can take to address the issue, several sources told The Herald.

“It’s important to realize that … urban renewal is one of the many tactics settler-colonists used to expropriate Indigenous land. Urban renewal didn’t destroy Indigenous people’s resolution to city living or their memories,” Rubertone wrote.

“Investing in housing is really an investment in a lot of aspects in our overall well-being,” Bull said. “Everybody has a right to live in a community that has quality services.”

But when services are upgraded in a community, there is a fear that it will draw in people of higher incomes and displace original members of the community, Bull said. Solutions to protect community members include increasing affordable and permanently protected housing, she added. But she noted that there are challenges in scaling up these efforts.

Another strategy involves compensating long-term homeowners by slowing increases in taxes, said Ritchie, as some homeowners struggle to afford property taxes that steadily increase.

At the institutional level, community benefits agreements help address the needs of communities, Bull said. These agreements, which originated in Los Angeles and are now more widely used across the country, involve negotiations between community representatives and institutes so that if the institution expands in some way, it must make contributions to the community in exchange, she added. Such agreements have been effective in some cases around other college campuses, according to Bull.

Ritchie also hopes to see a community-campus advisory board created to look into issues of gentrification and housing. The goal is to have something “collaborative in a shared power arrangement” that is permanent and stable, in order for community members to have ways to protect themselves and prevent further displacement, she said.

Katy Pickens was the managing editor of newsroom and vice president of The Brown Daily Herald's 133rd Editorial Board. She previously served as a Metro section editor covering College Hill, Fox Point and the Jewelry District, housing & campus footprint and activism, all while maintaining a passion for knitting tiny hats.

Rhea Rasquinha is a Metro editor covering development and infrastructure. She also serves as the co-chief of illustrations. She previously covered College Hill, Fox Point and the Jewelry District. Rhea is a senior from New York studying Biomedical Engineering.