Women occupied 21.7% of all STEM faculty positions in the 2020-21 academic year, according to Phase II of the Pathways to Diversity and Inclusion Action Plan, which was issued by the Office of Institutional Equity and Diversity in 2021.

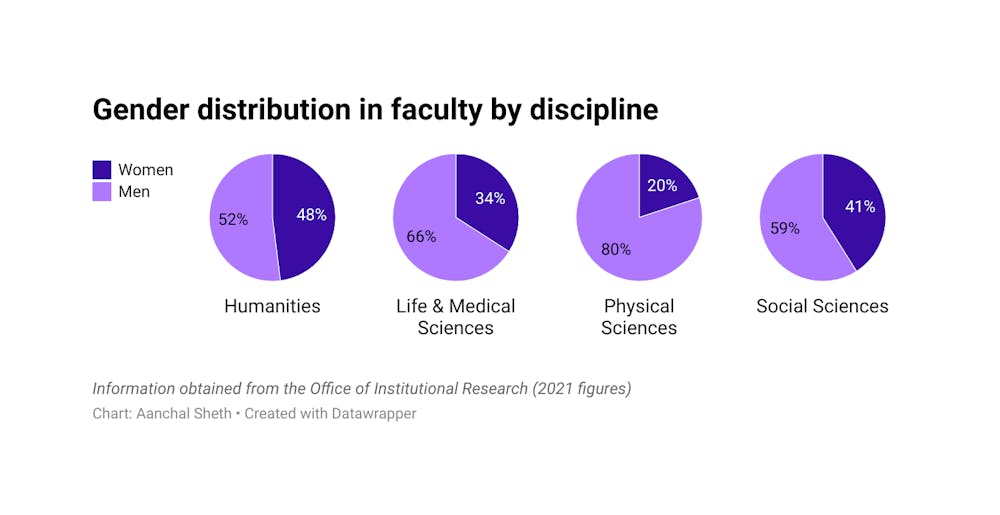

According to the report, among subsections of STEM fields, physical sciences have the lowest number of women in faculty positions. Women made up 20% of all faculty members in the physical sciences in fall 2021, an increase of three percentage points from fall 2020, according to the Office of Institutional Research Diversity Factbook.

The University does not currently list the number or proportions of nonbinary or gender-nonconforming faculty. According to the factbook, the University “is currently working on a process for collecting nonbinary information that will be used for internal reporting.”

“Gender remains a huge issue among faculty,” said Vice President for Institutional Equity and Diversity Sylvia Carey-Butler, who highlighted efforts to increase the proportion of women faculty members such as the Task Force on the Status of Women Faculty and the Presidential Postdoctoral Fellowship.

According to Professor of Physics Meenakshi Narain, this gender gap is indicative of a nationwide lack of pipelines for women studying STEM disciplines to enter academic careers.

“For the faculty, … our fractions (of women in STEM) are, in the last few years, similar to what the national averages are,” Narain said. “Our issues in STEM here are mostly the usual pipeline problems.”

“You need to work on the environment to keep students that go to the (postdoctoral) level and then become faculty,” she said, adding that some women in the physical sciences “choose an industrial setting over academia.”

Narain noted the importance of role models in motivating students to eventually pursue faculty positions.

Narain added that many laboratory researchers pass additional work to postdoctoral workers, which can make laboratory environments less welcoming to women in postdoctoral positions who are also considering starting a family.

“For the female postdocs, these little things and many others add to the pipeline issue,” Narain said. “We have to work on benefits and making (academia) family-friendly.”

Among faculty, women often have less time to complete academic work such as research in part because of an unequal distribution of household work and a greater demand for their political labor on campus, according to Senior Lecturer in Gender and Sexuality Studies Denise Davis.

"It's about the economies of time," Davis said. "Women of color have it much harder than I do, for example … with committee work. When you don't have a lot of women of color on campus and you want representation on all different committees, then you have someone galloping from one committee to another, one meeting to another."

Multiple undergraduate STEM concentrators noted the importance of learning from a diverse group of professors.

The professor’s gender “does affect (a course’s experience) in terms of how comfortable I feel approaching the professor,” said mechanical engineering concentrator Yesenia Gomez ’24.5. “The male students have a really easy time going up to the male professors.”

“I had a (male) professor that (when) I walked in, … the first thing he said to me was, ‘Wow, you’re the only girl in this tutorial,’” Gomez added. “The male professors see me as a woman in STEM and not just a student.”

Natalie Love ’23, a physics concentrator, added that having woman professors provides “some sort of assurance that there’s going to be a baseline understanding … of the unique challenges that you face.”

“There’s also that difficulty … of forming a connection with the professor because male professors are just going to be more receptive to male students and communicate in a more similar way,” Love said. She noted an incident where she was mistaken for one of the other two woman students in her class by a male professor.

Irene Wang ’22.5, an APMA-CS concentrator, noted that while having mostly male professors has not significantly affected her learning experience, the gender gap has been apparent.

“I’ve only had one professor who was a female for my STEM classes, and that was an introductory class,” she said. “I don’t feel like there was a huge difference (between male and female professors), but I’d love to have more female professors.”

The Task Force on the Status of Women Faculty is currently working to address the gender gap among faculty at Brown, especially within STEM, according to the task force’s charge.

The task force, with members selected by Provost Richard Locke P’18, is chaired by Senior Professor of Science Diane Lipscombe. The Task Force is currently gathering data and community input about the gender composition of faculty and will create recommendations to address any inequities they find, Lipscombe wrote in an email to The Herald.

The task force is focusing on tenure-track and tenured faculty. “At Brown, 36% of tenure-track (and) tenured faculty in 2021 were women, and this has remained constant for more than a decade,” Lipscombe wrote.

Currently, the task force is in its early stages, Lipscombe added. It is aiming to submit recommendations to President Christina Paxson P’19 and Locke “as soon as the end of May but before the start of the next academic year.”

“Thoroughness is paramount,” Lipscombe wrote. “We will have a more accurate assessment of the timeline once we complete the discovery phase of our task.”

The charge to the task force noted the detrimental impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the status of women in faculty positions.

“The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in new challenges but also amplified existing burdens on early-stage academics, and especially those with child and family care responsibilities,” Lipscombe wrote, adding that family-care responsibilities disproportionately fall upon women. “This coupled to the disproportionate attrition of women from academia is extremely concerning and the impact long-lasting.”

Neil Mehta was the editor-in-chief and president of the Brown Daily Herald's 134th editorial board. They study public health and statistics at Brown. Outside the office, you can find Neil baking and playing Tetris.