“The fraction of the As is getting pretty high — too high for comfort,” President Christina Paxson P ’19 told The Herald in 2014, pointing to the continuous grade inflation at Brown and at its peer institutions.

And since then, the trend has continued to hold strong.

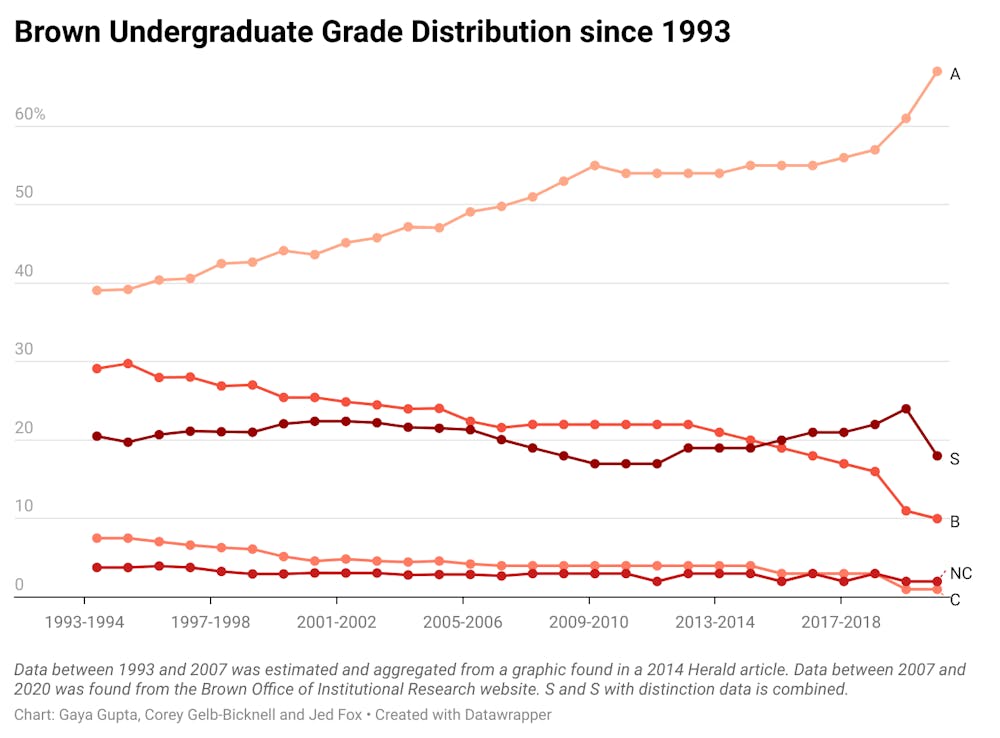

For decades, the proportion of A grades has steadily risen. In the past two academic years, which consisted largely of remote learning and saw some courses adjust grading styles, grade distributions rose to significantly higher levels.

Grade inflation is not unique to Brown. Students across the country in a wide range of higher-education institutions have transcripts that tend to have higher grades than their counterparts decades prior.

Recent data shows Brown has the highest average GPA in the Ivy League, and with average grades steadily rising, some members of the Brown community are grappling with the purpose of grades and the consequences of grade inflation. Students and faculty alike disagree over whether grades at Brown are intended to assist in learning, measure mastery of class material or act as a metric for employers.

The Data

In the 2020-21 academic year, 67% of grades were As — up from 39% in 1993, according to the Course Factbook on the University’s website and previous reporting from The Herald. In the Life and Medical Sciences disciplines, 74% of all grades were As — the highest percentages of As across all disciplines.

The portion of As in the last academic year at the University is up 10 percentage points from just two years earlier in the 2018-19 academic year — the highest percent increase since 1993. In contrast, the percentage of S grades dropped from 16% to 12%, suggesting that more students may have elected to take courses for a grade.

“It’s clear that the unique circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic played a role” in this recent shift, Paxson wrote in an email to The Herald.

Though data has not been released for the 2021-22 academic year, Zia wrote in an email to The Herald that grade distributions in the summer 2022 and fall 2022 semesters were somewhat lower than the past two semesters. He added that he believes grades will continue to “return toward pre-pandemic levels.”

The percentage of students receiving Bs and Cs have also decreased over the last 30 years. According to the Course Factbook and The Herald’s reporting, the portion of Bs distributed to students fell from 29.1% in 1993 to 16% in the 2018-19 academic year and 10% in the 2020-21 academic year, while the portion of Cs dropped from 7.5% to 3% to 1%, respectively. In the humanities departments last academic year, only 6% of students received Bs and 0% received Cs.

Brown had the highest GPA in the Ivy League for at least from the mid-1990s to 2012, but all eight schools have experienced an increase in average GPA since 1950, according to Vox.

One reason for Brown’s higher relative GPA is the University’s grading system, which allows for S/NC grading and omits Ds, failing grades and pluses or minuses, according to Dean of the Faculty Kevin McLaughlin. Brown’s system also allows for students to drop a course at any point in the semester, meaning that many students choose to drop courses if they believe they will not receive an A, according to Karen Newman, professor emerita of comparative literature and English.

Zia believes there are a number of reasons for particularly high grade distributions during the most recent academic year, when the school implemented a truncated three-semester model.

“Throughout the pandemic, we’ve consistently heard feedback from both instructors and students about how much time and care students committed to their studies, especially last year when many students were studying remotely and in-person extracurricular opportunities were more limited,” he wrote.

Zia noted that in end-of-semester course evaluations, a higher percentage of students reported attending every class session, completing all assignments and dedicating more weekly hours than in previous semesters. He added that students on average took 10% fewer enrollments while the three-semester model was in place than in previous academic years and that many first years took a single remote course in Fall 2020 before matriculating in the spring.

But McLaughlin believes that the recent increase in average grades largely reflects leeway given to students who battled hardships during the pandemic. He said that faculty evaluations have improved alongside grades.

“Maybe students are cutting the faculty a little bit of slack, too,” McLaughlin said. “Human sympathy for the person on the other side.”

Senior Lecturer in Political Science Nina Tannenwald agreed. “The rapid increase over the last two years surely reflects leniency on grading during COVID,” she wrote in an email to The Herald. “But it exacerbates a trend that has been under way for a while.”

Looking beyond the University

At the national level, grade inflation is neither rare nor inconsistent; grade distributions across the country have radically shifted over the past several decades.

In 1960, only about 15% of all college grades nationwide were As, compared to over 40% in 2008, according to a Teachers College Record analysis published in 2012. The proportion of Cs distributed among all colleges decreased from about 40% in 1960 to about 15% in 2008, according to the analysis.

In 2013, Harvard former Dean of Undergraduate Education Jay Harris announced that the most common grade at the college was an A, sparking a discussion about grade inflation at the school.

Jeffrey Miron, senior lecturer and director of Undergraduate Studies in the Department of Economics at Harvard, told The Herald that he doesn’t see grade inflation in higher education reversing in the near future.

“For every student focusing on their own grades, they will lobby for higher grades and choose courses with higher grades,” Miron said. “For any professor, it’s always easier to give students higher grades.”

“There's no one who can easily enforce (a lower) grade distribution,” Miron added.

National grade inflation may also be caused by an increase in pressure and competitiveness for elite post-graduate opportunities, which make a strong transcript “essential,” Professor of Engineering Allen Bower wrote in an email to The Herald. He also believes student performance has “genuinely improved” over the years.

At Dartmouth, among courses with at least 10 students, the proportion of classes which had a median grade of A rose by 13% in the three terms after the onset of the pandemic, according to the Dartmouth.

“Clearly there has been a progressive uptick in the share of As awarded in undergraduate classes on our campus and many of our peer schools,” Paxson wrote. “While it’s important to evaluate that data over time, the far more important focus for Brown is ensuring that the quality of instruction and the content of our courses remains world-class — and by every measure, that is the case.”

Some schools have implemented policies to combat grade inflation, but those attempts have faced significant challenges.

In 2004, Princeton tried to lower GPAs using a policy of “grade deflation,” according to the Atlantic, putting a cap on the proportion of As in each class at 35%. After nine years, the school ended its policy, citing that it “had unintended impacts upon the undergraduate academic experience that are not consistent with our broader educational goals,” according to the Atlantic.

Other schools have attempted to increase transparency around grade distributions to combat grade inflation. In 1994, Dartmouth made the decision to report grade medians of every class, in order to “allow ‘outside users’ of a transcript to get a better understanding of a student’s rank in their classes and because grade medians could potentially reduce grade inflation,” according to the Dartmouth. Still, Dartmouth’s average undergraduate GPA increased from 3.42 in the 2007-08 academic year to 3.52 in the 2017-18 academic year, the Dartmouth reported.

Reporting median grades may actually fuel grade inflation, since students may choose courses with higher median grades, Dartmouth Dean of Faculty for the Social Sciences and Professor of Social Sciences John Carey wrote in an email to The Herald.

Columbia instituted a similar policy to Dartmouth, reporting the percentage of students that share an individual’s grade on their transcripts, according to Forbes.

McLaughlin believes these top-down policies would never be implemented at Brown. “There’s a very strong sense of faculty and student government," McLaughlin said. “I would not expect grade policy changes to be something that the administration imposes on the campus,” he said.

Without changes to the University system at large, Lecturer in Economics Alex Poterack believes that national grade inflation is here to stay. “As tuition has gone up, universities have moved to more of a model where students are the customer,” he wrote in an email to The Herald.

And “the customer,” he added, “is always right.”

An Ongoing Conversation at Brown

Grade inflation has long been discussed at Brown, but opinions over the ideal grading system and distribution remain scattered. Often, disagreements stem from fundamentally different outlooks on the purpose of grades.

Some believe grades are meant to measure relative student performance as a means of providing information to that student and to potential employers.

“If we're going to give grades, I think they should send a signal of how well the student learned the material,” Poterack wrote. He believes grade inflation makes grades “less meaningful.”

To preserve the value of grades, Poterack caps the number of As in his courses to roughly the top third of the class — though he added that students who receive a grade greater than 90% are guaranteed an A.

Still, Poterack said he would rather have no grades in college than significant grade inflation. “If we're going to have the signal, it should be a useful signal,” Poterack wrote.

Tannenwald echoed this sentiment. “The problem is the fundamental bluntness of the evaluation system,” she wrote, referring to the University’s policy against giving out grades with pluses or minuses. “A student who is doing B- work in a course ends up with the same grade as a student doing B+ work.”

“It feels unjust and fundamentally unfair,” she added.

Bower made a similar argument, writing that a large portion of A grades means “some people don’t get recognition for exceptional work.” Bower also believes the lack of specificity in Brown’s evaluation metrics provide unreliable information at the borders between grade levels. “The difference between the lowest A and the highest B is very small, but this distinction can have a huge impact on a student's perceived success in a class and future prospects,” he wrote.

Tannenwald noted that although Brown’s Open Curriculum was put in place to reduce the emphasis on grades, the pressure put on instructors to bump student grades up is evidence the policy has failed to do so. “Brown students deserve a better grading system. And so does the faculty,” she added.

McLaughlin said he has not seen any official policy changes to tackle grade inflation at Brown during his tenure, though the question of incorporating pluses and minuses into grades has inspired public discussion several times.

In 2006, the College Curriculum Council voted on whether to add pluses and minuses to grades and rejected the proposal in a vote of seven to six, The Herald previously reported. In a 2003 poll conducted by the Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, 82% of faculty members supported the addition of pluses and minuses, The Herald previously reported –– but only 24.6% of students supported the proposal in the 2006 Herald poll.

Some others argue that inflated grades have little bearing on the habits and reputations of Brown students.

“You wouldn't get into this school if you were not in the top 5% of your (high) school,” Alex Cooper-Hohn ’23.5 said. “These are all people who worked very, very hard to get into here, and it's not like the academic habits are going to shift astronomically.”

“Employers already know Brown students are smart,” Cooper-Hohn said. “It comes with Brown’s reputation.”

But Kevin Masse ’25 argued that grade inflation can allow privileged students to gain status through Brown without having to meet high standards.

Still, Cooper-Hohn believes limiting high grades could be detrimental to student learning. “I have a really good friend who got a 70% in organic chemistry and who loved computational biology,” Cooper-Hohn said. “After he got that grade he said, ‘I'm clearly not made for this,’ ” prompting a switch to pursuing finance.

Ultimately, Cooper-Hohn said, the end goal of college should be to support the “mastery of skills to add to society.”

Ella Spungen ’23.5 suggested that grade inflation may also promote student learning by alleviating anxiety. “The pressure cooker environment is not conducive to learning. … I would rather there be a focus on students' mental health and well-being and have professors get creative with ways to motivate students that go beyond grades,” she said.

Spungen added that grades are never a perfect metric, as they do not necessarily reflect “how difficult or intellectually challenging or stimulating a class is.”

Zia agreed on the importance of prioritizing learning over assessment, but argued that testing and grading can be crucial to the learning process. Graded “assignments provide students with an opportunity to consolidate knowledge, to apply their learning to new topics and to gain feedback from instructors on how they are doing,” he wrote. He also quoted the 1968 student-written “Draft of a Working Paper for Education at Brown University” — a document that helped inspire Brown’s Open Curriculum and grading policy and argued that performance evaluation is just one of several benefits of testing.

“We’ll continue to track data on undergraduate grades over the next few years to see if that stabilizes,” Paxson wrote. “If at any point there is a need to explore measures related to how students are assessed, we would look to the Brown faculty to develop the best approach.”

Correction: A previous version of this story contained graphics and interactives titled "Brown Undergraduate Grade Distribution since 1993" that used partially incorrect data. The updated graphics have been fixed with the correct numbers. The Herald regrets the error.

Grace Holleb was a University News editor covering academics and advising.