What does this mean? 18 likes… Who is liking what? My dad’s voice buzzes through my phone speaker, my dog’s howling and the distant chirping of birds coiling into the spaces between his words.

“It means that 18 random people found your playlist on Spotify and liked it, and now they probably listen to it sometimes,” I reply, laughing into the early autumn air as I walked to a friend’s dorm to watch Naruto. “That’s actually pretty cool, Papa. I think my most popular playlist has 4 likes.”

What can I say, beta. Your father is pretty cool. I’m glad your studies are going well. I’m going to get back to walking Baloo and listening to my cool music. You should come home soon. Your mom has been feeling low and missing your sisters, and she’s been missing you. You know that Mama wants your sisters to move back to the East Coast. Now that Lily’s been born, your mother and I have been struggling with the distance. San Francisco is just too far away for us. Hey, you better not move there!

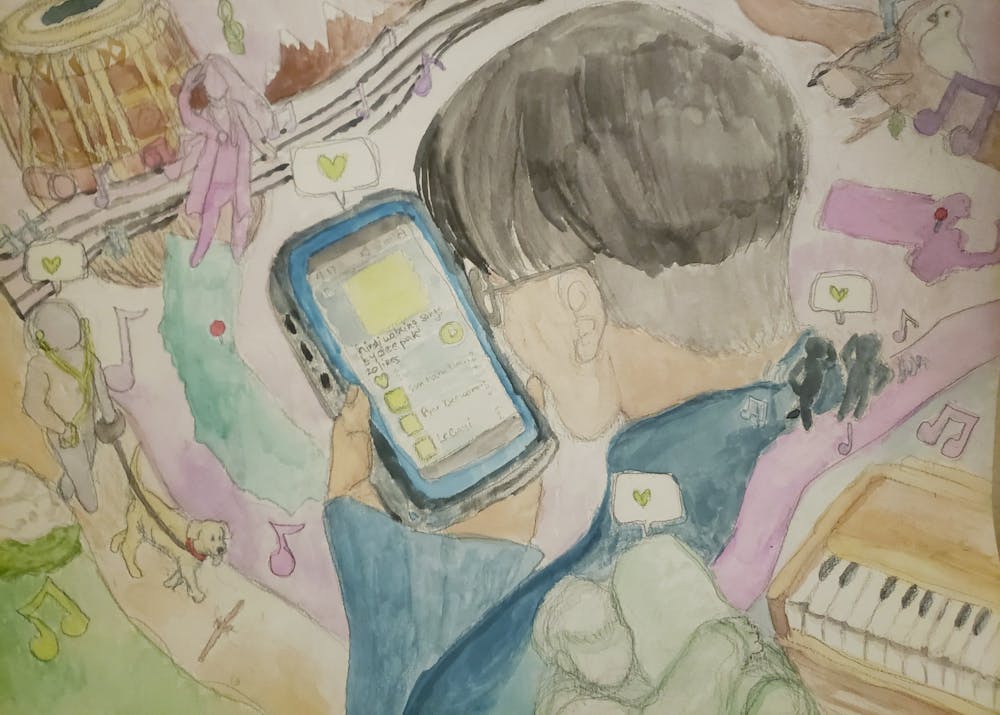

“No plans to move anywhere yet. I’ll make sure to call her soon, but the semester just started. My friends are here, and I don’t really want to come home just yet. Bye Papa!” I hang up the phone, open up Spotify, and search for his playlist. It came up immediately, hindi walking songs by the user deepak. I looked at his two other public playlists, prayer and bruce (an ode to one of his favorites, Bruce Springsteen). I follow him, press the little heart on my screen, and added one to the 18 likes. I save it to listen to later.

**

One night over winter break, after a snowy walk and a particularly competitive video game session, my best friend Danny and I lay on my bed looking up at the ceiling.

“Have I told you about my dad’s playlist yet?” I asked.

“No, what! I think my dad only listens to old Russian music on CDs,” Danny replied, chuckling quietly.

“Yeah, turns out my dad has a Spotify and has this playlist with like, 19 likes. I was the 19th actually. Pretty funny, right? I haven’t listened yet actually.”

“Wanna listen?” Danny asked. I took out my phone and showed him the playlist.

“Look at this one, called Sun Raha Hai Na Tu Unplugged by Shreya Ghoshal. Means ‘You’re listening, right?’ It’s from this Indian MTV Unplugged album. I didn’t even know there was MTV Unplugged in India.”

“Woah… looks cool. Put it on.”

I rolled over, hauled myself out of bed with a grunt and put the song on my stereo. The song opened with the simple, soft, mellifluous runs of a solo harmonium—a traditional, accordion-like Indian instrument that involves pumping air into a small keyboard.

“Wow, the last time I heard harmonium like this was at my aunt’s bhajans when I was a kid,” I recounted.

“Ohhh yeah, I remember going to a couple when we were younger,” he replied.

“Yeah, Shalini Bua used to host these monthly religious gatherings where everyone would bring instruments and sing Hindu chants. I remember there was an old uncle who played the harmonium. I used to sit in his lap, and he’d show me how to play. I hated going when I was a kid, but now I wish I had appreciated it more.”

As we chatted the music continued its runs. Suddenly, the solo harmonium was joined by the deep notes and infectious wobbling rhythm of tablas and dholaks, Indian hand drums. Shreya Ghoshal’s smooth and precise vocals entered at the same time, weaving a tapestry between the instruments. Danny and I stood up simultaneously and made eye contact. We both began dancing and strutting around my room, laughing deep from our stomachs.

“Oh my gosh, this is amazing!” Danny exclaimed through tears. “I cannot believe your dad walks around Lexington, Massachusetts to this. This is literally the best walking music ever.”

“Agree. I don’t know what I was expecting from this playlist, but this is better than anything I could imagine.”

We finished out the song, dancing, doubling over with laughter, and discussing the absurd beauty of the image of my dad walking around to such epic music. Afterwards, we went into my parents’ room and told my dad that we liked his playlist. He made fun of our generation for always trying to go viral, identified himself as an influencer, and told us to go to sleep. Before we turned the lights out, Danny asked me to send him the link.

“There. I liked it. I’m number 20.”

**

“Once Papa passes, I think I will move back to India to finish out my life.”

My mom drops this bombshell while we are out for dinner over Thanksgiving break. My dad, my sister Shreya, and I sit quiet around the table.

“So, can I get you guys anything else?” The server barges in, wine menu in hand. We all make awkward dissenting noises, and he seems to purse his lips in response to the tension bubbling off our table. “Okay, don’t worry, I’ll be back!” he calls over his shoulder as he scuttles away, running his hand through his wispy hair.

“What do you mean, Mama?” my sister asks after a few moments of silence, her voice trembling.

My dad clicks his tongue. “Lata, you can’t just say things like this without thought. You know how this will upset the kids.”

“Well, I mean it,” my mom retorts. “I just can’t do this. I need my family around. And I hate California.”

“So instead of moving to San Francisco, you’d go to the other side of the world? Because of some arbitrary hatred of one of the biggest states?” Shreya asks, tears in her eyes. “Just to be clear, I have been bending over backwards to figure out how I can move back to the East Coast after med school. All my friends are in SF and it’s my favorite place in the world. And you’re so stubborn that you can’t even think about moving to SF even if Papa dies?”

“She’s right, Lata,” my dad adds. “Our parents supported us moving across the world. Why can’t we support our own kids and what makes them happy?”

My mom spotted the nervous waiter coming back. “Alright, whatever,” she interjected. “We need to order anyway. I just miss my kids, okay? It’s hard that they’re all so far. Let’s drop this.”

**

hindi walking songs was the defining sound of my winter. I particularly loved the old romantic filmi on the playlist, Bollywood songs that reached mainstream popularity. I liked to imagine my father walking briskly around our neighborhood in his particular way, with his long strides and swinging arms, his head angled downward as if to maximize aerodynamic efficiency. I liked that I knew he was listening to the rhythmic romance of Kishore Kumar and Asha Bhosle through his little green earbuds. The songs of a sweltering Punjabi childhood under the snow-capped canopy of suburban Massachusetts.

My mom was particularly excited about my newfound connection with Indian music. One night, I sat at the kitchen table watching Naruto on my laptop, the spicy heartwarming smells of my mom’s cooking swirling in my nose.

“What language is this?” she asks.

“Japanese. It’s an animated TV show my friends showed me. I really like it,” I replied.

“If you like watching TV in a different language, why don’t you watch Hindi shows? There are some pretty good ones.”

“Really? The last one we watched together was too dramatic to handle,” I laughed.

“Okay, maybe. But they’re not all soap operas. Here, Papa and I just finished a great murder mystery set in the beautiful mountains of Himachal. It’s about a series of murders that a village attributes to the “nar tendua,” a were-panther. You’d be shocked to see what remote parts of India look like. Let’s watch it.”

After a bit of push and pull I begrudgingly agreed to watch it. Five nights of binging later, I sat on the edge of my couch, biting my nails through the season finale. Despite my puzzling, I couldn’t figure out who the murderer was, and I started to believe there might actually be a nar tendua. My mom was right; with all the Hindi songs and TV, I was getting a lot of language practice in. Even though it had never been a barrier, I even felt like I could understand my parents better. After the end credits played out, I asked my mom if she could teach me how to make a few of her dishes.

“Of course, beta. Just help me out for tonight’s dinner. We’ll make something good.”

I put hindi walking songs on the stereo, washed my hands, gave my mom a good hug, and got cooking.