When students returned to College Hill in the fall of 1970, they quickly encountered fliers asking a list of questions.

“Does it bother you that the secretaries at Pembroke earn less than the secretaries at Brown?”

“Have you ever wondered why only 8% of the faculty is female even though 53% of the population is female (and 30% of the graduate school)?”

The bills, posted by Beverley Edwards of the Chaplain’s Office, advertised a meeting on September 24, 1970 in Alumnae Hall. While previous women’s meetings featured small groups in Pembroke lounges, that meeting marked a vast expansion of feminist organizing on campus, forming what would become the activist group Women of Brown United. Over 100 women — faculty, staff, undergraduates and graduates — attended that meeting, including Mimi Pichey ’72, who went on to compile a comprehensive history of WBU.

“People came back to campus that fall with renewed vigor,” Pichey said. The fliers were printed on the heels of the Women’s Strike for Equality in New York, which drew attendance of 50,000 women in August 1970. And on campus, activists called for educational reform, racial equity, gay rights and the end of the Vietnam War, Pichey added.

“It was this incredibly fraught time in the nation, similar to what we are living through now,” said Mary Murphy, Pembroke Center archivist.

WBU, Pichey said, quickly became the voice of undergraduate women on campus outside of the Pembroke College administrative structure.

Pichey left the first meeting “excited about the possibilities of what we could accomplish if we organized,” she wrote in an email to The Herald. “I felt inspired, empowered and supported.”

“I knew we were making history,” she added, “and I felt that we were on the precipice of something monumental.”

On-campus activism

The formation of WBU in 1970 happened on a campus swirling with debates around the position of Pembroke in relation to the men's college.

“You had women at Brown who … had chosen to go to that school intentionally because of what people viewed as its progressivism,” said Andrea Levere ’77, who was a member of WBU while attending Brown. “It was the ideal pot to stir all of this up.”

“We were supposed to be represented through the Pembroke structure within the University,” Pichey said. “But women wanted to speak for themselves. Women of Brown United was the forum to raise our voices about things of concern to us.”

While Brown and Pembroke “had always been part of the same institution,” the two merged “under one banner” within the University in 1971, shortly after WBU was founded, Murphy said.

During and after the union of the colleges, WBU members advocated for the equal admittance of men and women into the University. According to Pichey’s historical account, in 1970 WBU demanded a one-to-one ratio for male and female students admitted to Brown by 1976. This goal would only reach completion over twenty years later in 1994.

WBU also promoted the hiring of more women faculty, as well as equal pay and tenure for women professors on campus. Per the history, in 1970 “the percentage of women faculty was 6.8% and tenured regular faculty were 3.9%.”

“In simple terms, students (live) and (work) within an institution existing without the participation — on a professional level — of an entire portion of humanity,” Levere wrote in an Oct. 1, 1976 op-ed for The Herald.

Levere noted the importance of Mari Jo Buhle, a history professor at the University who was the first faculty member to focus on women’s studies, in expanding course offerings on gender at the University. While discussing the increase of women faculty members, she also credited Louise Lamphere, an anthropology professor who sued the University for discrimination against women after being denied tenure in 1974.

Another key piece of WBU activism surrounded the creation of the Sarah Doyle Center for Women and Gender, according to the history.

“People began to see the huge need for a place for women” after the merger, Pichey said. WBU activists began petitioning, writing letters in The Herald and raising the idea for the center in “as many forums as possible.”

After advocacy from 1972 to 1975, the center opened at 185 Meeting Street, run by Edwards with a minimal budget, according to the history.

The lines between WBU and the center were blurred at the time, according to a 1975 article in The Herald: WBU housed six subgroups, though “women employees, the committee on women faculty, women of the Brown community and Alpha Kappa Alpha” also used the center.

Two years later, the center received full University funding. According to the history, the WBU budget request explained that a fully funded center would serve as a “central educational and informational resource” that provided space to bring women across campus together, including through WBU meetings.

WBU also included an expansion of women’s studies courses as one of its initial demands in 1970 — enough to “enable an independent concentration,” according to Pichey’s history.

Some success followed in the establishment of the first feminist course at Brown, “Anthropological Perspectives on Women.” But progress stalled by the time Levere reached campus. With help from Buhle, Levere “founded an independent concentration” in women’s history, writing a thesis about opposition to the Equal Rights Amendment among women, she said.

“It was really a sense of, ‘How do we pull together the classes that Mari Jo was teaching, along with other classes that aligned with focusing in on a social history?’” Levere said. She later organized the first independent concentration graduation ceremony, she said, which some professors attended instead of the ceremonies for their own departments.

In 1982, the University began offering a women’s studies concentration — emblematic of what Pichey described as a University trend toward absorbing and institutionalizing the activism of WBU. In addition to the new concentration and center, WBU activism led to the creation of the Brown/Fox Point Early Childhood Education Center, incorporated in 1979 and still functional today. In 1972, its activism helped prompt the introduction of reproductive health care on campus, according to the history.

“Women had no role models on campus,” Pichey said. “There was a three-to-one ratio of men to women on campus. Now there’s equal representation.”

The only place where WBU’s goals have not come to fruition are in balancing out the gender balance of faculty: In the 2020-21 academic year, only 30.3% of tenured professors and 38.9% of tenure track professors were women.

WBU’s final mention in The Herald came in 1991. The Sarah Doyle Center had taken the lead on much of WBU’s former work, Pichey speculated in the history. The group “served its purpose for over 20 years.”

LGBTQ issues and race in the movement

Throughout the second-wave feminist movement in the United States during the early 1970s, there were general tensions regarding lesbianism and the role queer identity would play in liberation.

“In the country at large, you saw this clash of early traditionalists who were not doing well around gay rights, women who were not being friendly to lesbian women,” Murphy said.

Pichey described that during the early years of WBU, gay activism on campus was only getting started. “There was a budding gay movement around the same time when I was on campus,” she said. “Most of the people who were in it were men — it was men who were the gay movement at that point. Over time, gay women became more active.”

“The anti-gay stigmas were very strong in those days,” Pichey added. According to Pichey’s history, inclusion of queer women in WBU and the Center was difficult initially. The Gay Liberation group, which sought to promote gay rights on campus, primarily served men, and lesbianism was “generally misunderstood and feared,” Levere wrote in a WBU file.

This led to the creation of Gay Women of Brown, a group organized under the WBU umbrella to provide support and allow advocacy and organizing specifically for lesbians. The group’s work and message was not always met positively on campus — in 1978, a bulletin posted by Gay Women of Brown was covered in black spray paint.

“The fact that such acts of intolerance and bigotry go unnoticed by the administration and the majority of the student body indicates a general unwillingness to recognize and face up the problems and needs of all minority groups on campus — (non-white) students, women and gays,” read a letter to the editor in The Herald written by WBU members.

But race and racism were not commonly discussed topics within the broader context of the feminist movement in the 1970s, Murphy said.

“The second wave women's movement … included racial disparity and required work around race that was not happening,” Murphy explained. “That is a criticism of that movement. We can be positive and inspired by it, (and) we can also be critical of it.”

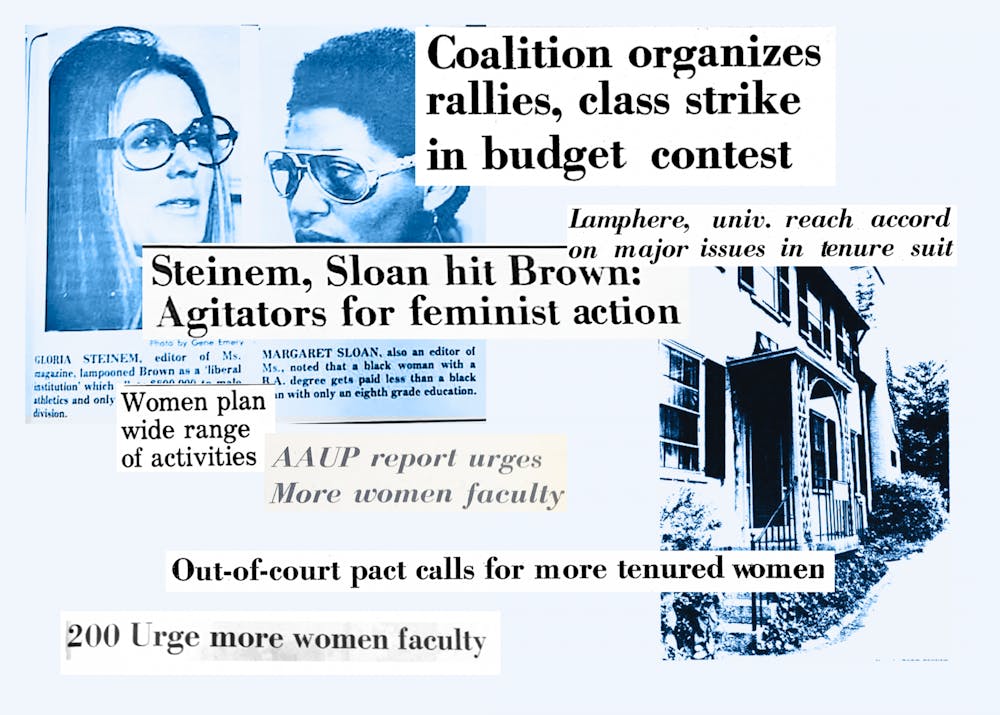

In 1972, there was only one Black member of WBU, according to Pichey’s history. While the organization did host a talk with Gloria Steinem and Margaret Sloane on “Sex and Racism” in 1973, and the Dec. 2, 1970 WBU meeting specifically emphasized that “efforts must be made to hire non-white women,” racism was not a common focus of WBU’s activism.

“I can see where the gaps are (now),” Pichey said. “History comes, and you do the best you can with making it as you go along,” she added.

Abortion

WBU’s abortion subgroup played a key role in the organization, Pichey said. When the group was founded, planning quickly started for a conference aiming at the repeal of state laws restricting abortion, which in turn helped spark lawsuits that eventually proved successful after the Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade, according to the history.

Pichey added that the simple act of talking about abortion was radical. Before, if a woman “got into trouble” while at the University, she was sent away to “have it taken care of,” she explained.

That may have meant going to a home for women to carry the pregnancy to completion and putting the child up for adoption, but it could also mean crossing international lines — Mexico for some students, or Sweden or England for wealthy students — to undergo the procedure, she said.

“It was not something that was ever talked about,” Pichey explained.

The first group meeting took place in a Pembroke lounge with 10 women — three of whom had undergone an abortion. One was the wife of a graduate student who raised $600, the equivalent of more than $4,300 in 2022, to receive an illegal procedure, Pichey said.

“She showed up, and the (practitioner) said, ‘Okay, hop up on my kitchen table,’” Pichey said. “For some of these women, it was the first time they had told anybody they had an abortion.”

After Roe v. Wade, WBU continued its abortion activism. In 1981, The Herald published an op-ed from a student who bused to Washington, D.C. with the Doyle Center and WBU to protest the “Human Life Amendment,” a catch-all name for constitutional amendments meant to effectively outlaw abortion.

In 1985, it began a service that offered to help “patients seeking abortions safely enter the Women’s Medical Center through groups of anti-abortion protestors,” the history said. WBU also published “resource guides” to “contraception, abortion and sexuality services,” according to Pichey’s history.

Ahead of this summer, numerous Supreme Court analysts have predicted that the court will weaken abortion rights, if not entirely overturn Roe v. Wade.

Pichey, who currently works with the Warren Alpert Medical School on including reproductive health and justice content in the medical curriculum, encouraged current students to “use every means available” to raise their voices.

“That means being out in the streets. It means legal participation in class action suits. It means supporting the providers,” she said. “You can’t give up. We cannot give up.”

“When I started Brown, I thought feminism had won,” Levere noted. “How wrong we were.”

Katy Pickens was the managing editor of newsroom and vice president of The Brown Daily Herald's 133rd Editorial Board. She previously served as a Metro section editor covering College Hill, Fox Point and the Jewelry District, housing & campus footprint and activism, all while maintaining a passion for knitting tiny hats.

Will Kubzansky was the 133rd editor-in-chief and president of the Brown Daily Herald. Previously, he served as a University News editor overseeing the admission & financial aid and staff & student labor beats. In his free time, he plays the guitar and soccer — both poorly.