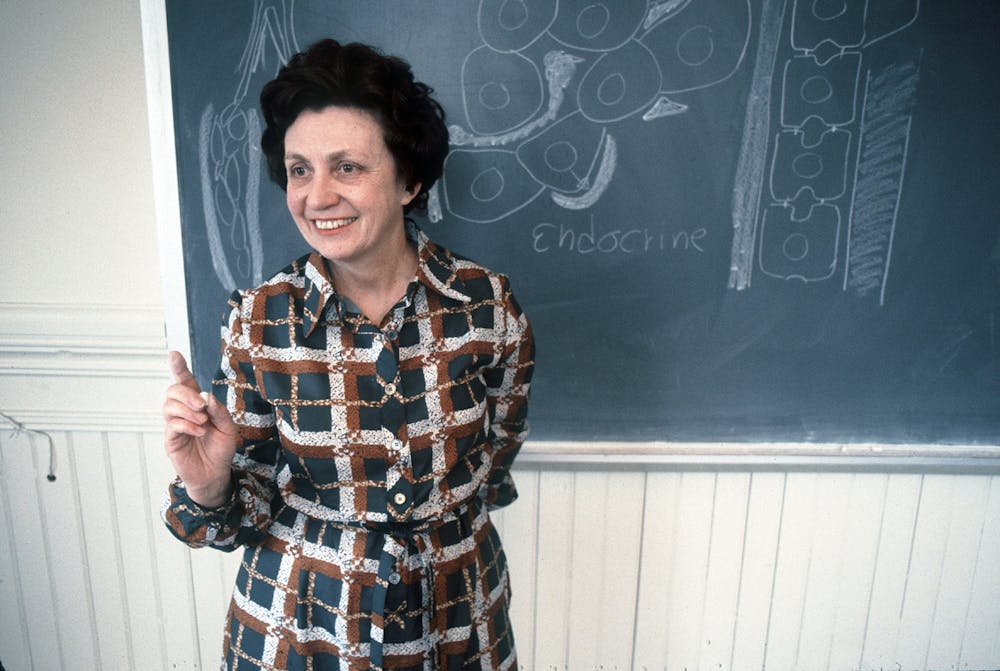

Elizabeth Hortense Leduc PhD'48, affectionately nicknamed “Dukie” by colleagues and students alike, was the first woman full professor in a teaching position at Brown University.

Beginning as a professor in 1964 after working at Brown for several years, Leduc helped shape the University for its women students — from inspiring future academics as the first woman chair of a department to helping oversee the merger between Brown's undergraduate college and Pembroke College in the 70s, Leduc left a tangible legacy on Brown.

Leduc is fondly remembered by colleagues and students who came to know her warm personality and admire her brilliant contributions to the field of biology.

Life and career: pioneering biology

Born in Rockland, Maine and raised in Vermont, Leduc graduated from the University of Vermont with a bachelors in biology in 1943, according to the Pembroke Center Oral History Project.

She obtained a masters at Wellesley College and a Ph.D. from Brown in 1948, both in biology. After a four-year stint teaching anatomy at Harvard, Leduc returned to Brown in 1953, where she remained for the rest of her career. In 1964, Leduc was made a full professor — seven years before the merger between Pembroke College and Brown's undergraduate college in 1971. Three years later, she briefly served as chair of the Biology Department, and from 1973 until 1977, Leduc served as the dean of biological sciences.

Leduc led an illustrious career as a researcher and professor. Her research “focused on the structure, function and pathology of the liver,” according to a Brown Alumni Magazine profile. She assisted in the development of cytochemistry, which allows scientists to identify the location of molecules within cells.

Leduc was an early pioneer in electron microscopy, a method that obtains high-resolution images of biological and non-biological specimens, according to Susan Gerbi, a professor of biochemistry.

The Leduc Bioimaging Facility, located at Sidney Frank Hall, provides equipment and training dedicated to high-resolution imaging in the life sciences and is named for Leduc.

Leduc published groundbreaking research and was highly regarded both nationally and internationally for her work. She was one of the founding members of the American Society for Cell Biology, according to Kenneth Miller ’70, a professor of biology who studied under Leduc. Today the society has over 7,500 members worldwide.

Miller recalled that she “always referred to herself as one of the founding mothers of the Society of Cell Biology.”

While Leduc served as an administrator at the University, she was appointed by former President Gerald Ford to the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, according to BAM. Leduc was the only woman on the committee, which was “charged with making science, technology and innovation policy recommendations to the President and the White House.”

Miller recalled Leduc as “a prodigious presence.” She wasn’t simply a token woman within the biology department, he said. She was extremely competent and accomplished, and “everyone respected her.”

Gerbi, who worked with Leduc, said that Leduc “was like a mother hen taking care of all the faculty, men and women alike,”

“She never seemed negative,” Gerbi added. “She was always such a happy person.”

Miller remembers Leduc as an optimist who he never saw not smiling.

“This was somebody who was just so happy to be at work advising students, teaching students or working in a laboratory,” Miller said. “She really thought that she had the best of all worlds … She was the kind of optimist who always thought she could make the best of any situation.”

As a professor, Leduc rarely used textbooks, according to Miller. She used original research material, including papers that were just published and images from her own work in electron microscopy.

Miller took Leduc’s course in cell biology during his sophomore year and said that her course was “a very realistic exposure to how science is actually done.”

“I just thought that it was cool that she trusted her students enough to basically say, … ‘You don’t need a textbook, where everything has been packaged for you. You can look at the real way that scientists communicate,’” Miller added. “She treated us all as though we were apprentice scientists, that we were all scientists in trade.”

Two awards at the University have been named in honor of Leduc: the Elizabeth Leduc Award for Excellence in Teaching in the Life Sciences and the Elizabeth Leduc Prize in Cell Biology.

“If I am proud of any award I’ve been given during my time at Brown, it’s the fact that the very first year the (Elizabeth Leduc Award for Excellence in Teaching in the Life Sciences) was offered, I was the recipient,” Miller said.

Benjamin Styler ’21 received the Elizabeth Leduc Prize in Cell Biology in 2021. The award is given to a senior biology student in recognition for a “remarkable record and research achievements in Cell Biology,” according to the Biology Undergraduate Education website.

“Getting that award … really inspired me to keep moving forward in biology,” Styler said. “Having that support from people who knew (Leduc) and were … partially mentored by her … means a lot.”

Integrating women at Brown

Leduc taught at the University during a time when Pembroke College was still a separate entity from Brown and the ratio of male students to female students between both institutions was two to one, according to an interview with Leduc conducted under the Pembroke Center Oral History Project.

Leduc was invited to chair the committee that oversaw the merger between Pembroke and Brown. She was initially wary of the two colleges merging.

“I was sort of defending Pembroke,” Leduc said in the interview. “I had this wonderful image of Pembroke … (The female students) did get specialized advising. It was well known that it was the best.”

Leduc was convinced that merging the two was the right thing to do when some of her colleagues and students, men and women alike, expressed their desire for change.

“I came away from it with the feeling that the students, the women, were telling me, ‘We are different. We have been set apart by Brown’ ... Everything must be the same. That’s what they wanted,” Leduc said. “I think it’s been better since (Pembroke and Brown merged). It really has.”

Still, even with the merging of Pembroke and Brown in 1971, there were very few female members on the faculty.

Gerbi, who Leduc helped recruit to teach at the University in 1972, said “it was a welcome change to come and visit Brown and find that (Leduc) was not only at Brown, but already was a full professor and had an important administrative role.”

“I didn’t feel like I was going to have to be the first to break ground,” Gerbi added. “She had already gone ahead and done that.”

“It’s important to remember her as a pioneer. She’s not someone who would ever have said that she faced enormous discrimination or prejudice and so forth,” Miller said. “She probably did, but she was just the sort of person who felt, and for good reason, that she could overcome any of that with a smile and hard work. And by God, that’s exactly what she did.”

Clarification: This story has been updated to more accurately describe the relationship between Brown University and Pembroke College.

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated Leduc's title in the headline as the first woman full professor. In fact, she was the first woman full professor in a teaching position. The Herald regrets the error.