The expanding impact of finance on American universities was discussed at a Tuesday evening virtual talk hosted by the Watson Institute. The event focused on a new book entitled “Bankers in the Ivory Tower: The Troubling Rise of Financiers in US Higher Education” by Charlie Eaton, assistant professor of sociology at University of California, Merced.

The talk also featured Josh Pacewicz, associate professor of sociology at Brown, as a speaker and Margaret Weir, professor of international and public affairs and political science at the Watson Institute, as moderator. It was sponsored by the Stone Inequality Initiative at the Watson Institute, which works to understand “how great wealth distorts (and) perhaps even threatens … the republic,” according to the Initiative’s website.

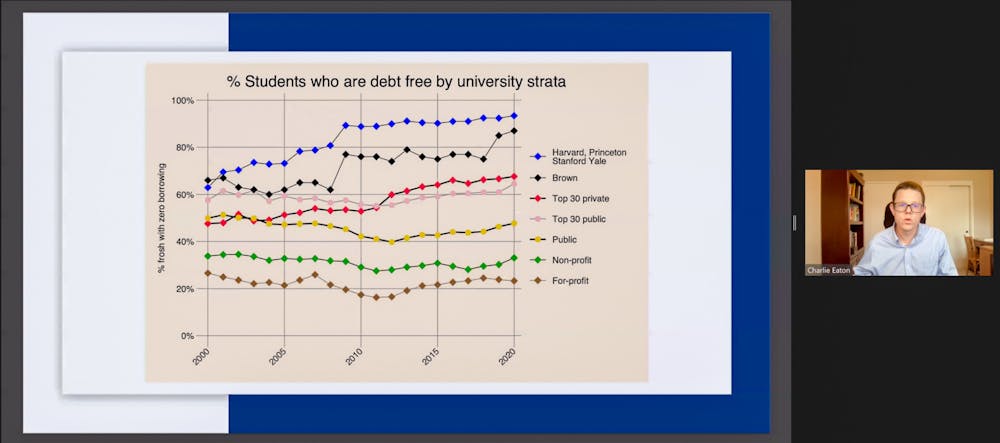

In his talk, Eaton explained how large financial institutions have come to play an increasingly important role in higher education, from skyrocketing student debt to growing financial control over university governance. These developments, Eaton said, have exacerbated pre-existing inequalities in race and class by diminishing educational outcomes at lower-tier schools and saddling students with thousands of dollars in student debt.

“Just one in eight undergraduates in the US had any student debt in the 1970s,” he said. “Today, a majority of college students leave school with the financial burden of an educational debt … There are large class and racial disparities in who borrows and who can afford to repay their debts.”

This growing trend of influence, also called financialization, Eaton argues, can be best understood by examining its impact on three tiers of schools: elite private universities, such as Brown, public universities and for-profit universities, many of which serve student bodies that are “overwhelmingly working class and disproportionately Black.”

In Eaton’s model, elite universities with large endowments benefit from deregulation and tax cuts, allowing a small number of often already privileged students to reap the benefits of financialization. On the other end, private financial institutions often take over for-profit universities to take advantage of public subsidies and students’ tuition, which often leads to university governance that prioritizes profit to the detriment of educational quality. Mid-tier public universities are then “squeezed” by pressure from both ends, Eaton explained.

One of the most important drivers of this financialization, Eaton said, was the passage of the 1992 Higher Education Act Amendments. These amendments eliminated the means test for federal student loans, doubled the undergraduate loan cap, eliminated the cap on parent loans and guaranteed a partial repayment of student loans by the federal government in the event of default.

These provisions, Eaton said, created the perfect environment for the proliferation of student loans.

“Was this policy shift really what led to the explosion of student debt?” he said. “In a word, yes.”

Much of the content of the legislation, he said, was submitted in congressional hearings by finance giants including Citi, Bank of America, Sallie Mae, Wells Fargo and JP Morgan Chase.

In addition to the precipitous rise of student loan debt, Eaton said, private finance also impacts university governance. In no type of institution is this clearer, he continued, than the private for-profit university. “Private equity managers acquired 994 for-profit colleges between 1988 and 2015,” he said. “They did so to capture tuition revenue from expanded loan programs. It’s hard to overstate how important this private equity invasion was in the explosion of enrollment at predatory for-profit colleges in the U.S.”

Eaton said that one example of this process is visible in the case of Providence Equity Partners, a private equity firm founded by Glenn Creamer ’84, Paul Salem ’85 and Jonathan Nelson ’77 P’07 P’09, for whom the Nelson Fitness Center and Nelson Center for Entrepreneurship are named.

In 2006, in cooperation with Goldman Sachs, Leeds Equity and KKR private equity firms, PEP bought out the Education Management Corporation, which ran a number of for-profit colleges in the “largest-ever acquisition of a for-profit college chain.”

Shortly after the acquisition, Eaton said, the chief financial officer of EDMC was forced out for refusing to prioritize economic growth over educational quality.

“Ultimately,” he said, “EDMC collapsed in bankruptcy because lawsuits and new consumer protection regulations thwarted its strategy” to divert large amounts of money to recruitment in an attempt to maximize profit.

Weir, the moderator of the event, said that she believes the book emphasized the “triple or quadruple bind that lower-income people face” in higher education.

After union-busting contributed to a decline in well-paying jobs that did not require a degree, she said, lower-income students were forced to experience price hikes, predatory lending and “useless degrees” from for-profit colleges that “focused all their resources on recruiting rather than education.”

Eaton said that despite their increasing financialization, American universities also contain within themselves the seeds of change. The engagement of many university communities with the Occupy Wall Street movement, he said, fueled pushes to make public universities more affordable in California. An effort by Columbia and NYU students in this same period even led to the Department of Education canceling student debts for “over 100,000 for-profit college students.”

“A better future is possible,” Eaton said, “if we mobilize a diverse and inclusive university to reimagine higher education finance.”