A team of Brown researchers is designing an assessment to improve the selection of cancer treatments in older patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

In their population-based study published Nov. 30, the researchers examined the impact of their assessment on treatment selections and outcomes in patients receiving home health care.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma “is an aggressive cancer of immune system cells” that has an average survival of months without treatment, wrote Thomas Ollila, assistant professor of medicine at the Alpert Medical School and hematologist/oncologist at the Lifespan Cancer Institute.

“Most commonly DLBCL is treated with a combination of immune therapy and chemotherapy and this can cure a substantial number of patients,” added Ollila, who was not involved in the study. “The average age at diagnosis is in the mid 60s,” so DLBCL patients often have comorbidities that render effective treatment more challenging.

These comorbidities correspond to a greater prevalence of chemotherapy complications in older patients, said first author of the study Mengyang Di, a clinical fellow of hematology/oncology at the Yale School of Medicine.

Providers typically decrease drug dosage or remove one or two drugs from the standard treatment to minimize the risk of these complications in older patients, Di added.

But applying this strategy to all older patients may be overly simplistic, Di said. Some of these patients can tolerate the standard regimen, so attenuating their cancer treatment may compromise their potential to be cured.

“As a clinician, deciding which older patient can receive intensive therapy and hopefully achieve a cure is challenging,” Ollila wrote. “I balance not wanting to undertreat, and thus deprive someone of (a) possible cure, with the risk (of) overtreating and causing more harm than good.”

It is therefore important to distinguish between older people who are able to tolerate intensive therapy without attenuations from those who are more likely to develop complications from the standard treatment, Di said.

To help make this distinction, the American Society of Clinical Oncology currently recommends that providers complete a comprehensive geriatric assessment in all older patients with cancer diagnoses.

This recommendation, however, “is very time and resources-consuming,” making it less feasible to implement in clinical practice, Di said.

The researchers wanted to design an abbreviated version that serves the same purposes as ASCO’s recommendation without losing significant accuracy.

To create this abbreviated model, they conducted a secondary analysis using a combination of data from three datasets: the Outcome and Assessment Information Set, the Medicare dataset and the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results dataset. The OASIS dataset, which comprises data that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services require home health care personnel to collect, includes a standard assessment of multiple geriatric domains.

The Medicare dataset includes information on treatment, such as when and how often patients received drugs, as well as treatment outcomes. The SEER dataset includes information related to cancer diagnoses and prevalence in the U.S. population. The researchers specifically identified home health care recipients with DLBCL from the SEER and Medicare datasets who also had OASIS evaluations.

Since health assessments are mandatory, the linked dataset provided “a unique opportunity to … passively accumulate data about population health” and develop a comprehensive model, said study co-author Emmanuelle Belanger, assistant professor of Health Services, Policy and Practice at the School of Public Health.

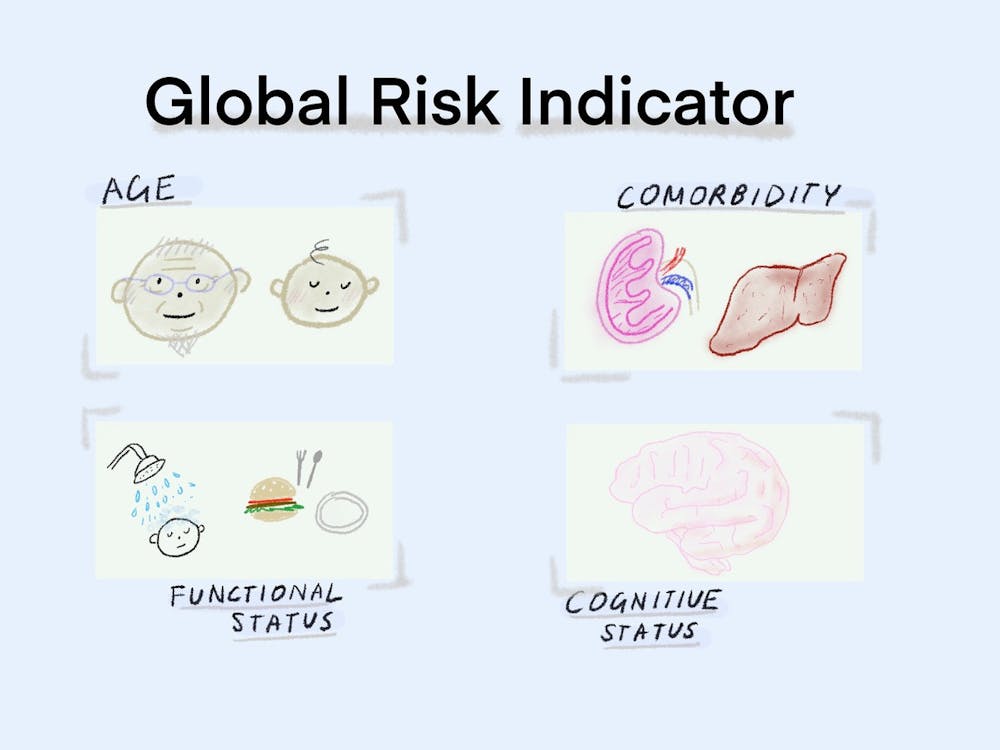

Using the datasets, the researchers created a single variable — named “global risk” — as a measure of age, comorbidity, cognitive status and functional status of patients. The group’s multidimensional assessment expanded on one created by Italian researchers, adding cognitive status because of the “increasing body of evidence” showing its key role as a prognostic factor in conditions such as lymphoma, Di said.

Patients were categorized as low, moderate or high-risk based on the researchers’ cutoffs for each of the four variables within the global risk indicator.

The researchers hope that the global risk indicator will allow clinicians to assess whether to give patients an attenuated or standard cancer treatment regimen and how likely they would be to develop complications if given intensive standard chemotherapy.

So far, the results have shown a “very strong correlation between the global risk indicator categories” and selection of intensive therapy by providers in real practice, Di said. They have also shown a “strong correlation” between global risk and the incidence of certain outcomes that may be indicative of complications after cancer treatment.

The study demonstrates that using OASIS may help in making decisions on the types of therapies to give older patients in clinical practice, Ollila wrote. It also “provides surprising information about treatment patterns in older patients and should be eye opening to how we can better treat this population.”

“This is just the first step of constructing this assessment,” Di said. “In order to use this assessment in clinical practice, we have to do a lot more work, including validation in a more general population.”

Possible ways to validate the model include designing a randomized control trial where some providers use the global risk model and others use standard assessment, Belanger said.

Belanger hopes the study reminds “people of the wealth of data that (exists) about these patients and how (this data) could be leveraged in practice” to improve cancer treatment selection.