A masked squadron in brightly colored jumpsuits, singularly focused, ready to kill at any moment, inspiring second-hand fear in the viewer. The game enforcers in this year’s Netflix phenomenon “Squid Game” might come to mind as fitting this description. This character depiction also manifests in the similarly masked, jumpsuit-clad, violent characters in Jordan Peele’s 2019 “Us,” or the Spanish crime hit “La Casa de Papel” or “Money Heist” in English.

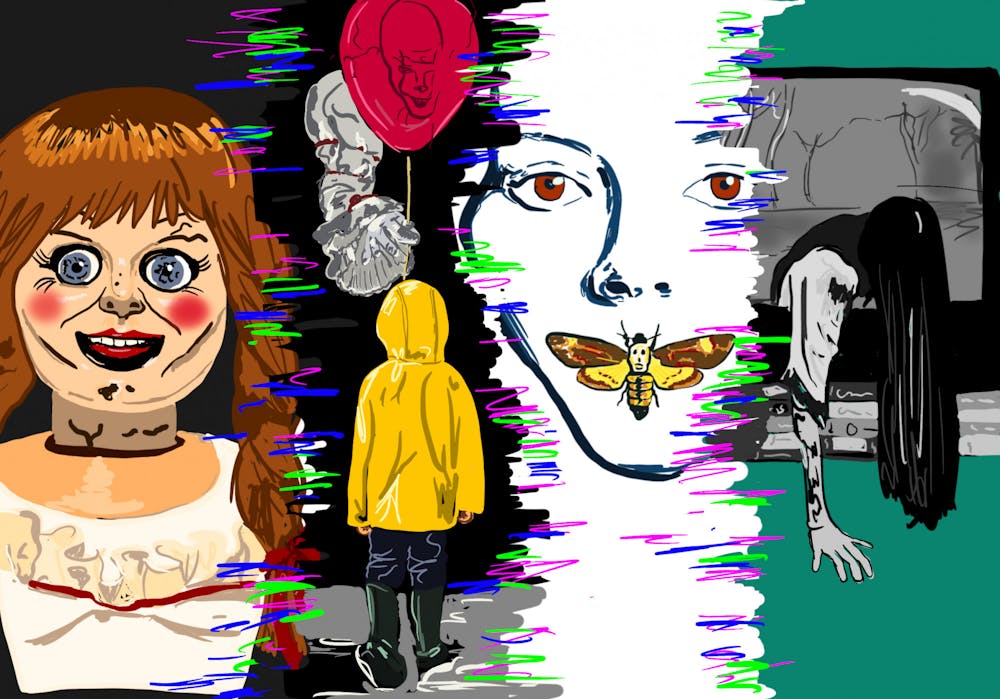

These massively popular productions show the power of manipulating common storytelling devices, social tropes and film techniques in different ways to get under the skin of millions of viewers. In tackling the themes most central to the human experience — life and death, good and evil and past and present — how we create and consume horror has become a valuable area of study for researchers across a variety of fields.

Roots of horror

Veronica Fitzpatrick, a postdoctoral fellow in Modern Culture and Media and the Cogut Institute for the Humanities, became interested in studying the horror genre because it was “the only genre that presents the world as frightening as it actually is,” she said. She is developing a dissertation on the significance of sexual trauma in modern horror films and will teach an MCM course in the spring on the genre.

The history of horror, or “cinematic explorations of violence,” is as old as the medium of cinema and can be tied further back to early spectacles like the public beheading of Mary Queen of Scots in 1587, Fitzpatrick said.

While early horror films usually portrayed fantastical monsters like vampires, most film scholars see the 1960s as the turn from classical to modern horror with movies such as Psycho, she said.

Retrospectively, modern horror appears to distinguish itself through a focus on the “mundane and the everyday” forms of horror, though Fitzpatrick argues that these elements have been present throughout the genre’s history. The horror genre — a nebulous, evolving category — has seen various kinds of horrific tendencies fluctuate in “peaks and valleys” of popularity, she said.

Fitzpatrick plans on exploring “the juxtaposition (or) intersection of aesthetics and ethics” in her course on horror films. The aesthetic techniques that a film utilizes change how it affects the viewer psychologically and as a spectator, she said. For instance, filmmakers can choose to create “quiet aesthetics,” which are intentional moments and atmospheres of silence, or, like in the 1974 classic Texas Chainsaw Massacre, use “loud aesthetics” of screams and overwhelming noise.

Psychologically, horror movies tap into a reaction in our central nervous system, said Mascha van ’t Wout, associate professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior (Research).

“A fear is super strong; it’s really built straight into our survival responses,” van ’t Wout said.

When a person witnesses or experiences a potentially life-threatening situation, it triggers a fight-or-flight response in the amygdala, the part of the brain and nervous system that processes emotions, leading to the production of sweat and other bodily responses.

While watching a horror movie, “your body responds to these images that you’re seeing, to some degree, as if you (were) there,” van ’t Wout said. The amygdala reacts to the threatening stimuli, perpetuating the same visceral feelings of being in danger, but knowing that the threat is harmless allows the body to keep watching, she said, instead of physically leaving the theatre. Horror movies are intentionally designed to activate the fear circuit and create a uniquely intense experience for the viewer, which may help explain why horror has fascinated audiences and been consumed as far back as it has.

Horror is a dialogue

Theorists have sought to explain viewers’ experiences with horror films.

American film theorist Carol Clover’s “final girl theory” proposes that, by the end of a horror film, the audience will begin identifying with the archetypal, single surviving female character. Assuming the viewer is a young man, to see the woman survive and defeat the monster figure creates a moment of identifying with someone of a different gender, Fitzpatrick said.

But this theory becomes much more complicated if the viewer is not male or young or does not primarily engage with films by identifying with the characters, she said.

Challenging and complicating existing theories and assumptions about the genre and how we engage with horror is not limited to media studies.

Andrés Emil González GS, a second-year PhD student in Comparative Literature, is taking an interdisciplinary approach to horror, most recently applying Carol Clover’s theories on female representation in horror media to art history. He is studying the different renditions of Caravaggio’s painting “Judith Beheading Holofernes,” in which artists have altered the way the woman Judith is depicted in the act of killing.

Reiterating the ideas presented in past works is important to the genre, said González, who explores horror’s many tropes and narrative conventions. “Conventions function almost as a kind of code or kind of language,” he said. The viewers can engage with that language in recognizing what is similar or different to other films they have watched and draw their own commentary.

González describes a “kind of play between the audience and the piece of media itself” as a significant component of horror. Which character will live, which will die? “It’s always kind of a game of watching,” he said.

Still, horror films and other works don’t have to be seen as derivative or be watched only as metaphors for socio-political issues. What can make a horror movie successful can be something conveyed that is not explicitly laid out or even understood on a conscious level, González said. “The great thing about (horror) is you don’t necessarily have to have a sense of why it works.”

In Latin America, horror has been “making a huge resurgence … as a mode of expression and fiction” over the past few years, Mai Hunt GS, a sixth-year PhD Candidate in Hispanic Studies, said. Hunt is teaching LACA 1505A: “Haunting Childhood and Social Justice in Latin America” this semester.

One film the course explores is “Fever Dream,” a Spanish psychological horror film just released on Netflix that involves a young woman, a child and a looming environmental disaster. Hunt suggests that the novel, which the film is adapted from, discusses these environmental issues tangibly and creates “opportunities to (also) discuss environmental crises more openly in popular culture,” she said.

The deep history of magical realism in Latin America, with popularized authors like Gabriel García Márquez exploring the mystical in a real world setting, lends itself well to new developments in horror, Hunt said. But her course dives deeper into the understanding of the genre and aims to “think critically about what magical realism means to the rest of the world versus what it means to Latin American artists.”

Much of the understanding of magical realism comes from Western elite intellectual circles, Hunt said. By using supernatural films as vehicles to discuss magical realism beyond associations from popular culture, Hunt hopes to explore alternatives to Western thought that may be closer to the true origins and essence of the genre.

In his course ENGL 0711C: “Bad Blood: Conflict and the Family in Literature and Cinema,” Christopher Yates PhD’21, a visiting assistant professor of English, hones in on what can be gleaned from “domestic gothic” horror, or works that focus on the home as the site of violence and involve characters who are haunted by something in the past. The genre turns the idea of the home as a place of safety and refuge on its head, while exploring how the past can manifest in the present. It’s about “a past that is never as gone as we’d like it to be — a past that still continues to shape our current present, even from beyond our current control,” he said.

In his course, Yates also plans on comparing the American film “Poltergeist” and the Japanese film “Ring,” which come out of different cultural contexts but are able to be discussed by shared audiences, Yates said. “Horror all around the world has a strikingly consistent vocabulary. In some ways, it does feel to me like a quite unified genre.”

Facing internal fears

While horror is an entertaining pastime for most, van ’t Wout is part of a research effort to prove that watching and confronting our greatest fears has potential as a form of treatment for those with post-traumatic stress disorder.

PTSD causes the amygdala to become prone to overreacting to harmless stimuli, such as a loud sound in another room, she explained. In those without PTSD, stimuli register through a slower route through the prefrontal cortex, which recognizes the stimuli as harmless in context and has a “calming-down effect” on the amygdala. But this regulatory process is thought to work less effectively in those with PTSD.

Her research uses virtual reality as a clinical tool to simulate the experience of being back in a combat zone. With the VR headset on, study participants are immersed inside of a combat vehicle, looking out of the windshield, while electrodes attached to the fingers measure skin conductivity rate, an indication of the psychophysiological arousal of the nervous system that activates the sweat glands and increases conductivity.

As explosions and other major stimuli are set off in the virtual environment as the vehicle moves forward, skin conductivity rates spike for veterans both with and without PTSD. Skin conductivity reactivity gradually decreased after repeated trials for both groups, showing that all veterans appear to “habituate similarly over time,” according to the study.

This change is due to a learning process that the brain undergoes, which recalls the memory of the fear from the first time watching the VR combat scene and registering the fear as harmless in subsequent viewings. Van ’t Wout calls this process “a deeper learning of extinction” of the fear. For the participants with PTSD, the VR helps with the “contextual experience of their trauma,” allowing their brain to learn that the stimuli that was life-threatening before is not in new context.

But, most promising is the research’s findings that PTSD symptoms for veterans with the disorder continued to decrease a month after the treatment, van ’t Wout said, “because they’re more likely to do things … (that) they’ve tried to avoid because they’re scared.” One veteran who participated thanked her for allowing him to go on a vacation for the first time in a decade.

Van ’t Wout is continuing to develop this research and hopes that these non-invasive brain stimulation techniques can become valuable additions to existing treatment for PTSD.