The number of students enrolled in both Korean language and culture courses at the University has increased in the past decade despite the small size of Korean studies and language staff.

This trend is more pronounced among non-heritage students, who now outnumber the traditionally larger number of heritage students in many classes in the Korean department. Heritage students are those who are ethnically Korean but not fluent in the language.

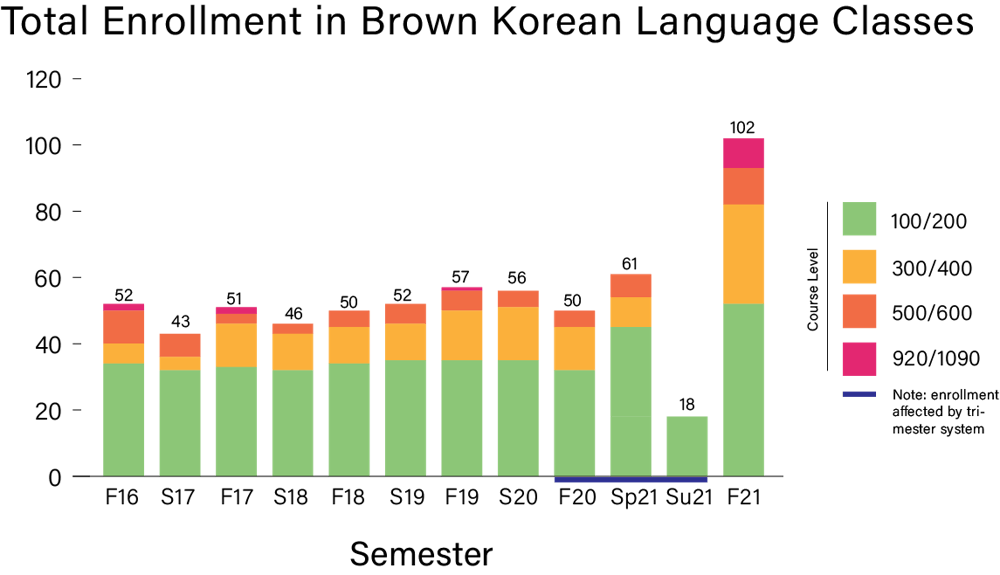

A rise in enrollment

Hye-Sook Wang, associate professor of East Asian Studies, came to the University as a Korean language professor in 1993. Throughout her time at the University, Wang said, she has not seen such high levels of interest in Korean culture and language study until now.

During shopping period this fall, Korean language classes saw unusually high levels of interest from the student body, resulting in one class, KREA 0300: “Intermediate Korean” becoming over enrolled. Wang said that the department ultimately created a second section of the course for the fall 2021 semester, which nearly became full itself.

“A lot of students showed up, and they wouldn’t go away. They kept saying, ‘I want to take this class,’” Wang said. “We just had to make a case to the department, and eventually to the University. In my 30 years of working here, this had never happened.”

Wang added that the trend of increasing enrollment in Korean language classes “has been continuing for the past several years.” But she emphasized that one of the most notable changes in Korean language classes has been the shifting makeup of the classes. Non-heritage learners have surpassed the number of heritage students in most Korean language classes at the University.

“When I first came to Brown, for quite a while, Korean classes were filled with heritage speakers coming from a Korean ethnic background,” Wang said. “Typically, heritage learners have the motivation to speak with extended family in Korea and find their roots.”

Wang said in the past decade, interest from non-heritage speakers has increased not just at the University but in Korean language classes across the country.

“I did one survey in around 2009 targeting several universities on the East Coast to see whether (there) is a trend right now in terms of class composition, student background and so on, because I noticed at Brown that there had already been changes going on,” Wang said.

Growing cultural influence abroad

Regarding why non-heritage learners want to learn about the language and culture in Korea, Wang stated that there are different reasons. “As you can imagine, the popularity of Korean popular culture, K-pop, K-drama, K-film, K-food, K-beauty, K-game,” are growing, she said. “A lot of non-heritage speakers are very interested in Korean popular culture.”

She added that “more and more students are interested in going to Korea these days. In the beginning of our courses, we collected the student information sheets … I (was) particularly interested in learning about a lot of students saying that, ‘After I graduate, I would like to go to Korea and work there in the K-music or K-film industry.’ (Some students) would also like to teach English in Korea, which I really didn’t see much some time ago.”

Wang also said that a number of complex factors go into the success of K-pop and K-drama. “It’s not just the people who made the drama or music, but also, the Korean government spent a lot of money to promote these Korean products.”

According to Ellie (Yunjung) Choi, visiting assistant professor of East Asian Studies, “the whole ‘getting Korea on the map’ really started with ‘Gangnam Style’ and Psy, (the song’s artist who) opened the door for bands like BTS. The biggest reason why Korea is so popular is also the power of the fans and social media to overcome media national boundaries.” Choi added that with the help of movie streaming platforms such as Viki and Netflix, K-movies have also become increasingly popular.

She further cited social media exposure and financial resources as other major factors causing Korean entertainment to become more widespread: “Korea has been a member of the (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) for a very long time, and … social media allows the fans to transcend national boundaries and regions and connect.”

Within the Department of East Asian Studies, Choi is teaching courses related to Korean history, Korean youth and identity and nation, Korean film and K-drama, Korean media and Korean trends. “I try to provide what’s relevant to young people … Students really appreciate issues that are relevant to their lives,” she said. “Right now, we’re talking about historical trauma and Korean-American parents and how inherited mental health affects Brown University students who are (of Korean) heritage.”

Student motivations

Students who have taken courses with Choi shared different reasons for their decision to study Korean language and culture.

Maliha Islam ’22, a non-heritage student, said she decided to take a course on Korean film with Choi because she wanted to take a film course. “It wasn’t an easy class, but it was a really worthwhile class,” Islam said. “For the Korean language classes, I had a friend who took them. She said that when she took those classes, she loved them a lot, so I decided to give it a try.”

Islam also liked the atmosphere of Korean classes and the Department of East Asian Studies. “I remember that when I took the language classes, they used to do Korean language tables, where there would be lots of food and snacks, lots of talking and watching films. It had really nice vibes. The professors were also really accommodating, … if there’s anything else going on, they would support you and would teach you how to say it in Korean, too.”

Thomas Sze ’22, another non-heritage learner, cited diverse motivations. “I’m Japanese, American and Chinese, so I think that by approaching Korean history, you can see how those three countries really have long-lasting effects in the region, so it was a fascinating way to approach my own culture and history … I’ve also been interested in K-pop and K-media as an Asian person trying to look for representation in media.”

Heritage students had some different reasons for their study from non-heritage students.

“I am Korean-American, but I grew up pretty distant from Korean culture,” Isabel Kim ’22 said. Kim’s parents immigrated to the U.S. while young and “don’t (really) speak Korean.” As a result, she grew up “quite American.”

But while in high school, Kim grew more interested in her Korean heritage. She discovered K-pop and K-dramas before further exploring Korean culture and history beyond the Eurocentric focus of the history courses she took.

“For the first time, I felt proud of being Korean,” she said.

Before taking courses with Choi, Kim said she idealized Korea in her mind as the super-modern home of K-pop. “But in (Professor Choi’s) classes, you just learn a ton about the very complex history of Korea, which is filled with a lot of pain and trauma, and you learn about this hidden, insidious nature of the culture as well.”

Sumera Subzwari ’21 is half Korean, but hadn’t learned Korean while growing up. She took Korean language courses while at the University “to learn to connect with my mom's family in Korea and talk to them, while also learning more about this side of myself that I hadn’t explored yet, including cultural traditions and family history.” Subzwari added that she has been able to speak to her extended family and grandparents and that she is grateful for having been able to take Korean courses.

Regarding K-pop and contemporary Korean culture, Subzwari said that she would not have predicted the surge of popularity surrounding Korean culture a few years ago.

“It's heartwarming to see that people are becoming more exposed to Korean culture by first being introduced through K-pop, K-dramas and other aspects of pop culture, and then are becoming genuinely interested in the more traditions and historical culture as well,” she said. “As a child, people often made fun of Asian culture or just lumped Korean culture together with the broad Asian continent and didn’t think it was a rich, beautiful culture of its own.”

Isaiah Paik ’22, another heritage learner, also said that “my sociological interest in Korea and what it represents about global capitalism and (the) future, really made me interested in taking (Korean) classes.”

Regarding the rise of K-pop, Paik said that “the increase in enrollment in Korean classes at Brown is a good thing, especially for Korea — they are both a result of some people naturally being interested in the latest media and what’s going on and of a deliberate project by Korea to spread Korean media to the globe and make people become interested in it.”

Looking forward, Wang said she would like to add more sections to introductory and intermediate Korean classes and create more regular Korean faculty positions.

“Maybe everything has (its own) timing,” Wang said. “Now, it’s time for the Korean program to grow, and our students support (it) by enrolling in classes.”

Correction: A previous version of the graphic in this article misrepresented the levels of enrollment for Korean 200, 400 and 600 in the spring 2021 column. The Herald regrets the error.