My favorite scene in Crying in H Mart is one in which Michelle Zauner, the author, makes kimchi. Although making doesn’t quite capture what’s happening: it’s the obsessive flurry of Zauner’s hands across the page as she ferments, seasons, spices, bottles, stacks. Up to her wrists in wet red matter. Knees aching on the kitchen floor.

The scene is my favorite in part because of Zauner’s rich description—the way she translates obsession resonates with me. But most of all, I love the scene because it’s not really about making kimchi. It’s about grief.

Some pages earlier, we stayed by Zauner’s side while her mother died of cancer. Food was their shared love, their middle ground, Zauner’s cultural tether. So when she makes her mother’s kimchi recipe, she’s not just making kimchi. She’s monument-making. We’re holding a woman, made of words.

I used to avoid memoirs. I had an uncharacteristically cynical take: unless you were someone incredibly famous and influential in the conventional way, like a first lady or a prominent activist, why would you have something to say that was more worth publishing than any of the rest of us? I thought personal history and desires should be played out in novels: not sharing your life verbatim, but dressing it up in costume and sending it out into the streets like a trick-or-treater. That was interesting. A new take on your own life, but not just your own life.

Natasha Tretheway proved me wrong. She’s still famous and influential—United States Poet Laureate 2012-2013, author of multiple dazzling collections—but Memorial Drive isn’t about that. The book doesn’t meditate on metaphors or the anxiety of publishing your most personal thoughts in verse. It’s about her mother.

Her name was Gwendolyn Ann Turnbough. She grew up in the Jim Crow South. She sewed her own clothes, had a birthmark at the base of her head, and wore perfume. Her husband—Tretheway’s father—was white, and their marriage was not recognized by the state. The couple eventually parted ways before Gwen and Natasha moved to Atlanta, where everything would change. When Natasha was 18, her stepfather killed her mother.

But not right away. First there is how magnetic her mother’s beauty became when she danced. There’s the bunch of daffodils Natasha gave her Mom. The terrifying driving lessons with her stepfather, Joel. A new baby brother. An uneasy awareness of White Flight and harsh looks. Collecting tiny stones from the creek bed to make paths, when all roads didn’t lead back to one memory.

These memories of abuse, love, and fear are charting towards something both Natasha and the reader are simultaneously desperate to avoid and unable to shut out: “Look at you. Even now you think you can write yourself away from that girl you were, distance yourself in the second person, as if you weren’t the one to whom any of this happened.”

Memoirs are not fiction’s trick-or-treaters because their truths don’t need to dress up in anything to be monstrous. Tretheway goes so far as to put the transcript of her mother’s last phone call right on the page. The injury is bound in a book, balmed and stitched up with paper and ink.

My younger sister read Crying in H Mart after me, zipping through it in a day. I had joked with her about feeling like Zauner was my friend after I closed the book, and subsequently feeling offended and startled when I opened Instagram and remembered that she is a famous musician with thousands of followers.

I’m not sure that this intimacy could’ve come from reading about Zauner’s music career as Japanese Breakfast or her day-to-day life alone. To know someone’s mother is to know both the parts of them that the author wants you to know and the parts she doesn’t; it pulls back a curtain of years—through our upbringing, our parents blueprint much of the architecture of our future existence. People can decide whether or not to call on those manuals as an adult, but they’ll always have them in the archives.

The feeling we get when we read about mothers is something boundless and timeless. Visceral, as my sister and mother described it. To love that intensely. Whether someone’s mother is their best friend or someone they’ve never met, mothers leave their traces. We work our whole life to make sense of them, like lines on a palm.

Zauner and Tretheway’s memoirs are alive with more than just the memory of the women who gave birth to them. Their haunted family homes are full ones. Both their mothers come with a hefty constellation of people they’re responsible for and attached to. In South Korea, amongst a grandmother and several aunts, Zauner is a woman in a house of women, separated by a language barrier but united by something deeper. In the first chapters of Memorial Drive, Tretheway’s house is alive with the memory of her grandparents, aunts and uncles who lived in the neighborhood and filled the absence of Tretheway’s father.

All of these additional figures that pass in front of the windows of childhood are markers of their mothers loving and being loved. These relationships have a transformative and influential power over us in their own right: observing the ways the world moves around one of the most important people in our lives. As kids, many of us look to our mothers to see what love looks like; when it’s too loose, too tight, just right. When it’s life-giving or threatening.

In both memoirs, the mothers’ other relationships are never reduced to the periphery but charged with significance. Zauner seethes when her ailing mother’s close friend, Kye, comes to take care of her and assembles a barricade of whispered untranslatable words and home-cooked meals better than Zauner can make, providing her mother with a comfort Zauner knows she can’t replicate. It is from Gwendolyn’s time in an abusive relationship that Tretheway learns how to plot an escape. When the past becomes too painful to bear, she makes hers from Atlanta, and vows never to return.

When I think of the ways my mother loves and is loved, I think of the comments my Dad makes that send my mom into helpless laughter, their silhouettes in the driver and passenger seats. People who have taken her hard work for granted. Old stories of my Mom insisting upon adopting a stray dog named Annie despite my grandma’s protestations. I feel lucky to inherit my Mom’s capacity for love, a basin sculpted by the innumerable hands that clasped hers.

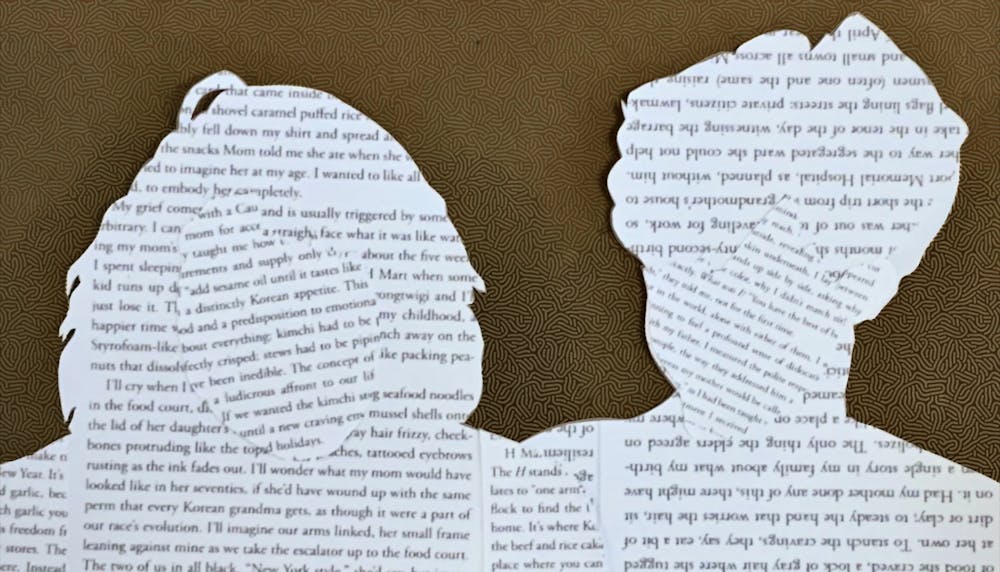

I wonder what she would write about these loves. What she would write about her own mother—the parts I don’t know—and what each mother before mine would write. I wish I had all of their memoirs. But since I don’t, I cut out space in my personal history for these unknown ones and fill it with imaginary women: women who loved. Who stayed. Who left. Who saved themselves, so I could be here, writing them down.