The School of Public Health’s Innovations in Behavioral and Social Health Sciences Seminar Series held its first lecture this year on Friday, Oct. 8, with Yale Assistant Professor of Psychiatry Angela Haeny presenting on the impact of racial trauma on substance use treatment for Black adults and on broader health considerations.

Haeny’s research expertise aligns with the i-BSHS Series’ four focus topics: “health disparities, community engaged research approaches, technologies applied to health promotion and novel behavioral health interventions,'' according to series co-chair and Associate Professor of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Epidemiology Diana Grigsby-Toussaint.

In her talk, Haeny examined the effects of racism on health and how clinical work and research can consider systemic inequities. To illustrate this, she highlighted several key statistics: Black people experience among the highest rates of substance-use related consequences yet fewer than 25% with substance-use disorder receive treatment. Treatment retention and satisfaction also tend to be lower among Black adults than other populations.

Recent research has found an association between racial discrimination and negative health effects such as increasing anxiety, depression, binge eating and panic disorder, among others, all of which may decrease one’s “perceived control,” Haeny said.

It was in her own graduate school training that Haeny first noticed the need for increased research to combat these realities. During her time at the University of Missouri, where she completed her PhD in clinical psychology in 2018, Haeny recalled navigating a charged period of racial tension in the local community. The injustices around her during this period led her to experience considerable emotional stress — yet when she opened up about her experiences to a fellow trainee in her program, she was amazed to learn that her colleague didn’t understand the situation at all.

Despite being “in the same department and the same training program … it felt like we were living in two completely different worlds,” Haeny recalled.

Haeny soon began hearing of others’ “experiences of racial stress and what sounded like racial trauma,” she said. “As a clinical psychology trainee at the time, I could identify that the things that they were describing sounded like trauma symptoms and yet, in the training program… I didn’t hear anything about racial trauma.”

An entirely new aspect of substance use disorder research unfolded before her. After training primarily as an alcohol researcher, Haeny transitioned to examining other addiction mediums and recently received a K23 career development award to study the role of racial trauma in substance use disorders.

In her lecture, Haeny explained that the first step in understanding the role of racial trauma in substance use treatment is to study the contexts in which that trauma is formed.

She began by defining microagressions, a term coined by Derald Wing Sue and colleagues in a 2007 study. The study defines them as “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral and environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory or negative racial slights and insults to the target person or group.”

She then discussed a 2018 study published in The Lancet which found that “highly publicized killings of Black people … have spillover effects on the mental health of Black people in the region in which the killing happened,” she said. At least 135 unarmed Black Americans have been shot and killed by police officers since 2015, according to a recent NPR study published in January of this year.

The prevalence of such killings, coupled with the speed of modern information spread, makes the impacts of vicarious trauma especially heavy, according to “Call in Black,” a video Haeny played during her lecture.

Haeny also pointed out the pervasiveness of “Color-blind racism,” the idea that one can or should navigate the world while ignoring the complexities of race. This, Haeny explains, is harmful to people of color as it “invalidates experiences of racism, ignores valued aspects of racial identity (and) maintains whiteness as the status quo.”

Expanding upon this theme, she next discussed colorism — the internalization of negative messages within one’s own racial and ethnic group. “This is not necessarily equivalent to self-hatred or low self esteem,” she said. “The reality is the insidiousness of racism is that all of us are kind of socialized to beliefs that may be happening outside of our awareness.”

Other race-related health factors Haeny discussed were environmental racism — the disproportionate placement of waste materials, pipelines and hazardous substances into communities of color — and medical racism. “People of color are disproportionately bearing the harms of science where white people are disproportionately bearing the benefits of science,” Haeny said. General racial barriers to employment reinforce the wealth gap between white and Black Americans, further limiting their access to critical health treatments, she added.

“It's important that we are operationalizing these terms, so we can better identify how these different factors contribute to health outcomes,” Haeny concluded.

Through their research initiatives, Haeny and her colleagues are attempting to do just that. She pointed to strong pride in one’s racial or ethnic group, how often one discusses challenges unique to their racial background with others and one’s general sense of belonging to their racial or ethnic group as strong factors in mitigating the risk of substance abuse disorders in communities of color.

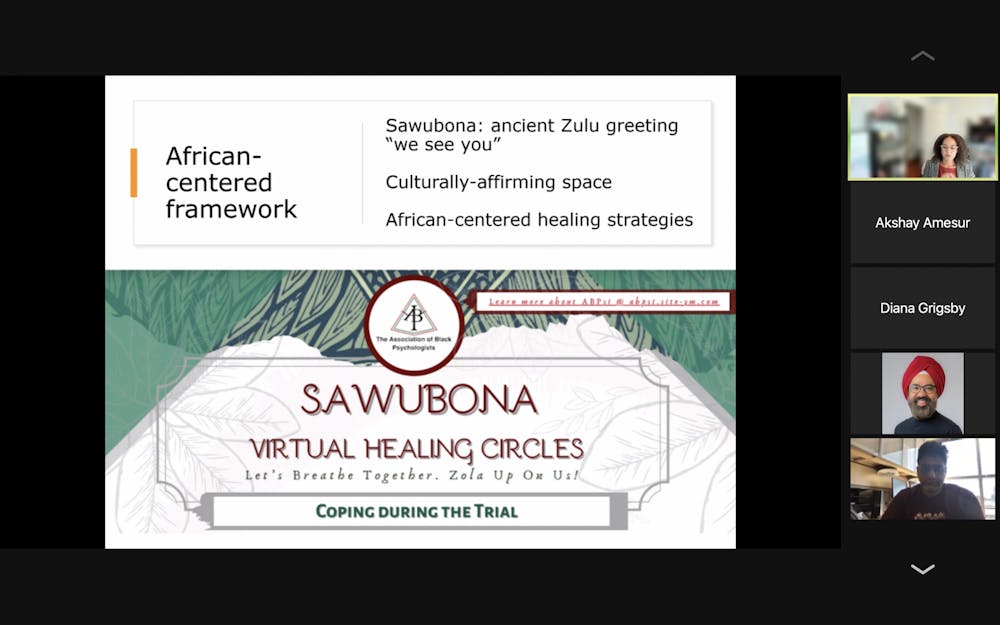

In light of COVID-19, Haeny and her colleagues have put together a program known as the “Sawubona Circles,” a place where members of local Black communities can come together to discuss their experiences of race-related stress and trauma. Haeny describes it as “a space (where one may come to be) fully seen and heard and validated … a culturally affirming space that focuses on African-centered healing strategies.”

Careful to point out that the Sawubona Circles are not meant to be therapy groups but rather community support systems and forums for open discussion, Haeny also highlighted the word “Sawubona” as an ancient Zulu greeting loosely translating to “I see you.”

As the i-BSHS Seminar Series continues, Haeny hopes to see continued focus on racial and equity considerations in medical research, such as including people of color through all stages of the research process.

“Due to the recent increased attention to broader societal implications of anti-Black and systemic racism, we are interested in inviting speakers to help our department continue to contextualize the historical and contemporary factors that have resulted in a disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on Black, Indigenous and people of color,” Grigsby-Toussaint said. She added that Haeny “is an excellent speaker to start off our 2021-2022 seminar series.”

The seminar series will continue Nov. 5. with the year’s second i-BSHS speaker, Peter Hovmand, a professor at Case Western Reserve University.