Twenty years ago, on the eve of Sept. 11, 2001, life on Brown’s campus proceeded as normal. It was a sunny day at the tail end of summer, and, in passing, students read Herald stories covering last night’s Undergraduate Council of Students meeting and the construction of a new English building.

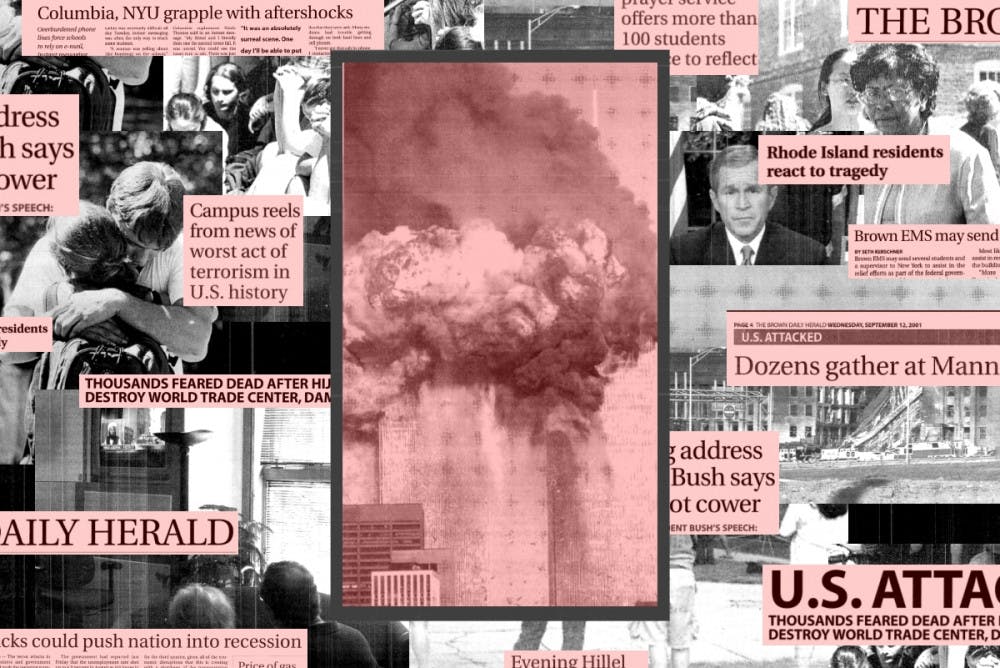

Yet in just 24 hours, campus was transformed. Pathways filled with students comforting one another, some crying, some silent. Others sat glued to their television screens in shock and confusion. At the center of everyone’s mind was the series of four coordinated terrorist attacks taken on the United States’ soil — and the previously unimaginable loss and destruction that came with it.

Across the nation, the aftermath of 9/11 instilled in communities a need for information, truth and ultimately, a reason why. And, for many, the search for answers began with the media, leaving journalists responsible for deciding which stories to tell and how to tell them.

The search for answers

The turn of the 21st century ushered rapid technological development into the American media landscape. In journalism, technological growth was reflected in how the public consumed its news: split between print and digital media.

Although she owned one herself, “cell phones were really just for voice then,” said Katherine Boas ’02, co-editor-in-chief of The Herald during 9/11. With fewer features and a less user-friendly interface, “these were not smartphones. And people didn’t rely on them like we do now.”

Instead, with television, radio, print news and the up-and-coming internet, the United States sat at the precipice of an uncontested digital age.

On Brown’s campus, “television cable news was the primary way that we got news about what was happening then,” Patrick Moos ’02, Boas’ co-editor-in-chief, recalled. It was through cable news that Moos and his roommate heard about the attacks in the first place.

The aftermath of 9/11 gave student journalists on College Hill a newfound duty: to capture a national conversation, explaining what happened and what it meant for the Brown community. As student journalists leading The Herald when the attacks happened, Boas and Moos found themselves central bearers of this responsibility.

“I don’t want to make The Herald seem more important than it was, but certainly there was a reliance on paper newspapers in a way that there might not be today,” Boas said. “So, to have a physical copy of The Herald was important to us, and we hope important to our readers.”

“I don’t think on Sept. 11, or Sept. 12, or Sept. 13 we understood the gravity and the world-changing nature of what had happened. Everybody was in shock,” she added. “There was a lot of confusion, and we were just trying to do our jobs. So, was there pressure? I don’t know — there was pressure every day to do the best job we could.”

When the attacks happened, Moos added, The Herald immediately began coverage, documenting how the Brown community was responding and what was occuring on the national level, including “wires,” or stories transferred from major news outlets, in the printed paper. “I don’t actually remember specifically how I kicked into gear in terms of trying to think like a reporter, but I know that, within a few hours, certainly all of us were at The Herald and trying to figure out what we would put in the paper,” he said. For days and even weeks after Sept. 11, the attacks remained central to The Herald’s news coverage, with spreads of 9/11-related stories on every page.

Major media organizations were essential in addressing confusion and grief following 9/11 on a national scale. For Kimberly Millette, Office of Military-Affiliated Students program director, she and her family relied upon brief glimpses of televised media coverage as they tried to make sense of the tragedy.

The attack “was very dramatic at school,” said Millette, who was a freshman in high school at the time. “Everybody was upset because some students had family members that were in the area, so there was a lot of confusion.”

But Millette grew up in a traditional household where topics like 9/11 were not something her parents readily addressed. “I was pretty sheltered,” she explained. On Sept. 11, Millette remembers seeing her mom watching the news on the television and crying, but the two never discussed it.

At the time of the attacks, Millette’s father was a member of the Army Reserve, making the events hit even closer to home.

“Dealing with their own emotions through it … I just think they didn’t have the capacity to have that conversation with us, me and my sisters,” she said.

Confronted with a level of violence deemed unspeakable, Millette’s family experienced 9/11 in silence, allowing the media to do the talking.

Nationalizing narratives

Recently, scrutiny over the media has grown in the general American consciousness, and the public has begun to reexamine whether journalism can ever be devoid of subjectivity. But Millette did not grow up with this critical rhetoric. Within her community, ideological and social conservatism made for a culture resistant to ideas and influences from elsewhere in the country, and Millette largely took media narratives at face value.

In part, the perspective Millette gained from watching news coverage of 9/11 was one that honored the fallen and all who made sacrifices to help others in the aftermath of the attacks, especially first responders. Millette, who served in the United States Air Force for six years, noted that acts of service from first responders created a legacy of respect across the country, but even more so in military spaces, instilling in many Americans a sense of duty to protect their nation.

“Even Brown alumni that I talk to say that they served because of 9/11,” she said. “Even (for) our current veterans, (the anniversary of the attacks) is something that every year is impactful to them, even if they were children when they happened.”

But while the media served as a tool to honor those seen as upholders of American principles, narratives it perpetuated also often cast out Muslim Americans from an otherwise national identity.

“Back then, I wasn’t educated about media … and how stories can be told in certain ways,” Millette said. “I thought anything I see through the news — it’s truth, that’s just how I was raised.”

Following the attacks on Sept. 11, the United States saw a sharp rise in violence against Muslims. According to Sreemati Mitter, assistant professor of Middle Eastern history and international and public affairs, the stories told by the media tap into sentiments that already exist in our society. Islamophobia was not created by the events that transpired on Sept. 11, 2001 — it had been lurking beneath the surface of American society, and was suddenly viewed as an acceptable sentiment to have and publicly voice at the expense of Muslims, Mitter explained.

Predicated on an understanding of who was American and who was not, this shift resulted in the targeting of ethnic minorities perceived as Muslim, Mitter said. She noted the experiences of discrimination faced by her Muslim and non-Muslim Middle Eastern and South Asian friends alike, demonstrating the racialized targeting of people who “look Muslim,” and therefore do not fit into popular depictions of what an American is.

“Many South Asians were attacked, regardless of their religion or ethnicity, (because of) the racial perception of who a Muslim is,” Vazira Zamindar, associate professor of history, added. “And so it affected the South Asian community ... including non-Muslims.”

For example, Zamindar said, Sikhs who wear turbans “were read as Muslim bodies in (the American conciousness) that affected domestically what it meant to be American.”

Influenced by media narratives, Millette said her “elementary way of looking at (9/11) back then was there are terrorists, they don’t like America because we stand for freedom, and so that is why they did what they did.” It was not until adulthood and after her military service that Millette fully understood the history of American interventionism and conflict in the Middle East, in addition to the context surrounding the attacks, and gained a perspective informed beyond mass media coverage.

On the other hand, Moos said that some at the time did approach the media with caution, including on Brown’s campus. But in a moment of unparalleled grief, he felt the nation “did kind of drop that skepticism … at least temporarily, in the immediate aftermath of (9/11), because people were hungry for facts about what was happening, and the national news media was the only place to get any information.”

Twenty years later

In some ways, media coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic mirrors coverage of 9/11, showing consistencies in the way Americans interpret and experience tragedies. In the aftermath of 9/11, there was an honoring of first responders as American heroes akin to how doctors and healthcare professionals have been uplifted throughout the pandemic.

In other ways, the media during both events have featured a rhetoric of “othering” immigrants and religious and racial minorities, covering narratives that depict marginalized groups as responsible for national tragedies. The period following 9/11 saw a rise in Islamaphobic violence, and violence against East Asians spiked during the pandemic.

But not all racism and violence is perpetuated in the same way in the United States, Mitter said, noting that Islam has been associated, and continues to be associated, with violence, evoking a distinctly Islamaphobic fear of violence within the American mainstream.

According to Millette, a limited news consumption can give news organizations disproportionate power in shaping how people perceive reality, especially in tumultuous times. “I say that with love for my family, but they are all very conservative. Fox News is the only news that they watch, 24/7. So that is the information they’re getting, and we know social media is tailored to what our preferences are, in that we oftentimes will not see the other side’s opinions because it’s filtered out,” Millette said. Social media companies “know that we don’t want to see (conflicting ideas) … we want confirmation bias, we just want to see what we already believe.”

“I do think there is mass-generalization over an entire religion because of (9/11) without fully understanding what the religion is, and taking extremist action and rhetoric and assigning that label to everyone. Unfortunately, it is very common,” Millette added.

Despite the admiration first responders received in the media, Millette emphasized that that narrative of support was not always the full story.

“There was a period of time where the first responders of 9/11 didn’t receive the care and attention that they deserved,” she explained. “They have so many health issues now because of (their service), and so, even though we all see their service as amazing … they’re still fighting to get their basic needs met from the aftermath of it.”

For the people of the Middle East, military intervention following the United States’ Oct. 7, 2001 invasion of Afghanistan and the ensuing decades of warfare led to the “violent deaths” of more than 335,000 civilians, according to the Watson Institute of International and Public Affairs’ Cost of War Project. And, according to Mitter, these are the stories of loss and suffering following 9/11 that remain untold by most of the mainstream media in the United States. She pointed to a New York Times series that documented the lives of those who died during 9/11 while overlooking lives lost in the Middle East following U.S. military intervention. “Those photographs that I saw in the New York Times every day … we never saw a single photograph of an innocent child” from the Middle East who died in the war on terror,” Mitter said. She added that the full number of lives lost following U.S. intervention in the Middle East after 9/11 will likely never be known.

“We don’t have the faces and the names of the Afghani people” who died in the war, Mitter said. “There seems to be, at least in the U.S. press, no recognition — or not in the same way of the cost to human life when (those who have died) are not American,” demonstrating that not all lives are equal in their depictions by the mainstream media.

Jack Walker served as senior editor of multimedia, social media and post- magazine for The Herald’s 132nd Editorial Board. Jack is an archaeology and literary arts concentrator from Thurmont, Maryland who previously covered the Grad School and staff and student labor beats.