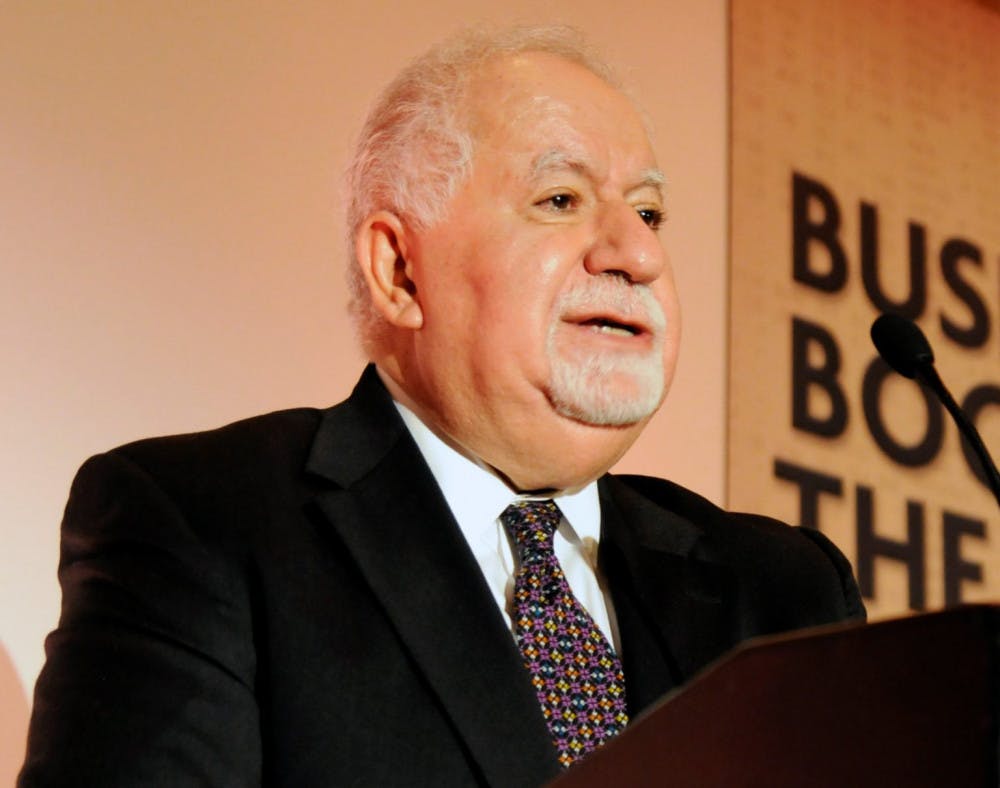

Former University President Vartan Gregorian, widely known for the academic ingenuity, benevolence and strong leadership he demonstrated during his tenures at Brown, the New York Public Library and the Carnegie Corporation of New York, passed away April 15. He was 87.

Gregorian was the first foreign-born president of the University, serving from 1989 to 1997. During his time as president, he grew the endowment, expanded professorships and bolstered research at the University.

Faculty members remember him for being welcoming and supportive, and as someone who would make an effort to start conversations with people on the Main Green no matter their position at the University. Gregorian, a “short, stocky man who had a bushy head of hair,” was also well-known for his bear hugs, said Stephen Merriam Foley ’74, associate professor of English and comparative literature.

At the time, Foley added, Gregorian, who spoke English fluently but with a heavy accent, was an “unlikely figure for an Ivy League college president.”

Birth of a lifelong learner

Gregorian was born to Armenian parents in Iran, where he first discovered what would become a lifelong love of learning. While attending school, he became an avid reader and would often educate himself outside of his lessons. Recognizing his potential, many of his teachers encouraged him to attend secondary school in Beirut.

“Learning was his key to freedom as a youngster,” said his son Dareh Gregorian. “He loved academia in large part because of what it did for him.”

Gregorian’s deep curiosity and love for learning made academia a “natural fit” for his eventual career, Dareh Gregorian added. He was awarded a scholarship to Stanford University in 1956, where he received a bachelor’s degree with honors in history and the humanities in only two years. He went on to earn his Ph.D. from Stanford in 1964.

Gregorian began his teaching career as a professor focusing on European and Middle Eastern history. He spent time at San Francisco State College, University of California at Los Angeles and the University of Texas at Austin before taking up a post at the University of Pennsylvania, where he later served as provost between 1978 and 1981. In 1981, he left Penn to become the president of the New York Public Library, which he is credited with saving from closure due to a financial crisis and a lack of morale and enthusiasm among its staff and board.

Gregorian would often stay in contact with students from 50 years before, Dareh Gregorian said, a testament to his tendency to go all-in in his endeavors.

“It always seemed to be kind of a pay-it-forward thing with him,” Dareh Gregorian said. “These teachers had helped him move along and succeed against really incredible odds, and I think a part of that carried with him.”

Making a name on College Hill

After being awarded an honorary degree from Brown in 1984, Gregorian was chosen to be the president of the University in 1989.

Dareh Gregorian remembers attending his father’s swearing-in ceremony, during which Gregorian “was happy as could be.”

Foley, who was a student at Brown before he returned as a professor in the 1980s, remembered the University as underfunded and “shabby” before Gregorian became president. Many classrooms had not been renovated since before World War II, and there were none of the science laboratories that have since become hallmarks on campus, such as the expanded BioMedical Center and MacMillan Hall.

“It was a very different place,” he said.

When Gregorian started at the University, he had the goal of helping Brown achieve its educational potential. He was successful in fundraising, being the first president to grow the endowment to above $1 billion.

“Greg had a great love of learning, and he loved parties,” Foley said. “I sort of think of his presidency as a series of parties to celebrate what Brown can do, and to seek resources to support that mission.”

During his tenure, Gregorian instituted 90 new endowed professorships and hired 270 faculty members. He also oversaw the creation of 11 new departments including Ethnic Studies, Modern Culture and Media, Portuguese and Brazilian Studies and American Civilization, as well as campus resources for marginalized students. He helped develop the Leadership Alliance, which worked with Historically Black Colleges and Universities to train professors from historically underrepresented groups.

“He was, in my mind, the start of Brown’s ascent as a research institution,” said Professor of English James Egan. During Gregorian’s presidency, there was an air of “ambition” and “a positive energy about the mission of the University and being able to achieve even higher goals than we had.”

As the first foreign-born president of the University, Gregorian also worked to bring many international students to the University, Foley said.

“His worldview — and his approach to higher education — was largely shaped by his experiences as an immigrant in the United States,” University President Christina Paxson P’19 wrote in an email to The Herald. “He strongly believed in the power of education to transform society. These convictions were evident in his leadership and continue on today in many ways, including through the work of Brown’s Diversity and Inclusion Action Plan.”

Reflecting his belief that the University had “an obligation to look beyond its borders and respond to pressing societal needs,” Gregorian established the Annenberg Institute for School Reform, Paxson wrote. The Institute “does incredibly important work to reduce educational inequality and improve educational opportunities for all students,” Paxson added, which continues today through initiatives such as the Providence Public School District’s Turnaround Action Plan.

On campus, Gregorian was a gregarious and buoyant presence for many faculty members.

Egan remembers Gregorian walking across the Main Green in the mornings as he came into work. Though Egan was an assistant professor at the time, Gregorian would always greet him warmly and ask how he was doing.

“I remember getting a couple of bear hugs from him,” Egan added. “Even though I never actually had any professional engagements with him, I felt supported. I felt like the president of the University might not know who I am, but he wants me to succeed.”

Lawrence Stanley, English lecturer and co-director of Brown’s Nonfiction Writing Program, commuted to campus at 7:00 a.m. and was similarly greeted by Gregorian on many occasions.

Wendy Schiller, professor of political science, recalls the dinners Gregorian hosted for speakers visiting campus. He would invite “a range of people, including junior faculty, which made them feel included in the Brown community,” she wrote in an email to The Herald.

“He was full of energy and was constantly roaming the campus talking to students, staff and faculty,” Schiller added. “Gregorian's love for Brown was obvious and he was the University's number one cheerleader both on and off campus.”

For Gregorian’s 61st birthday, his wife Claire surprised him by organizing a flock of sheep and lambs to graze outside of University Hall, a cheeky homage to an early University rule that stated that the president reserves the right to graze livestock on the Main Green. When he emerged from the building, the University band played “Happy Birthday” as numerous professors and students looked on. His wife also presented him with a shepherd's crook.

“He was utterly surprised and had nothing to say, which was totally uncharacteristic,” Foley said. “That was a moment of Brown family joy.”

After being selected as University president, Paxson met with Gregorian at his Carnegie Corporation office, where he gave her “sound, pragmatic advice” on beginning her leadership of Brown.

“He was simply one of those remarkable, larger-than-life people who makes the world a better place,” Paxson wrote. “His energy and exuberance filled any room he was in. He was also incredibly considerate and always went out of his way to make people feel welcome.”

Paxson referenced Gregorian’s 1997 State of the University address, which focused on the importance of intellectual freedom on campus and which she said has inspired her own work as president.

“Our University is and must remain a sanctuary for ideas, even unpopular ones,” Gregorian said in his speech. “We cannot and must not compromise this principle. Intellectual freedom — freedom of speech — cannot be rationed. It cannot be dispensed piecemeal or granted in limited fashion.”

After Brown

Gregorian was a “dedicated worker who threw himself into causes,” Dareh Gregorian said. After serving as president of Brown, he accepted a position as president of the Carnegie Corporation of New York. He was also involved in other charitable organizations such as the Children of Armenia Fund and the 9/11 Memorial and Museum.

When not working or dedicating his time to charitable organizations, Gregorian could be found reading and going “though piles and piles of newspapers,” Dareh Gregorian said. He also spent a lot of time with his grandchildren, who resided near him in New York City, though there were fewer opportunities to gather with family during the past year due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I don't think the Zoom life agreed with him,” Dareh Gregorian said. “He would mainly spend his time seeing people and being with people.”

Gregorian devoted his life to teaching and learning — as a young student in Iran, as a teacher who maintained contact with his students into their adult lives, as a leader who inspired respect and admiration even among those he barely met.

“When he gave himself to helping, he was in all the way,” Dareh Gregorian said. “He's had huge impacts in lots of different ways. It's kind of hard to quantify.”

ADVERTISEMENT