While on a trip to Washington D.C. for a national oratorical contest, John Aiso ’31 visited the Japanese Ambassador. It was there that the Ambassador referred Aiso to his friend, Brown University President William Faunce, in what Visiting Scholar John Eng-Wong called a “stroke of serendipity.”

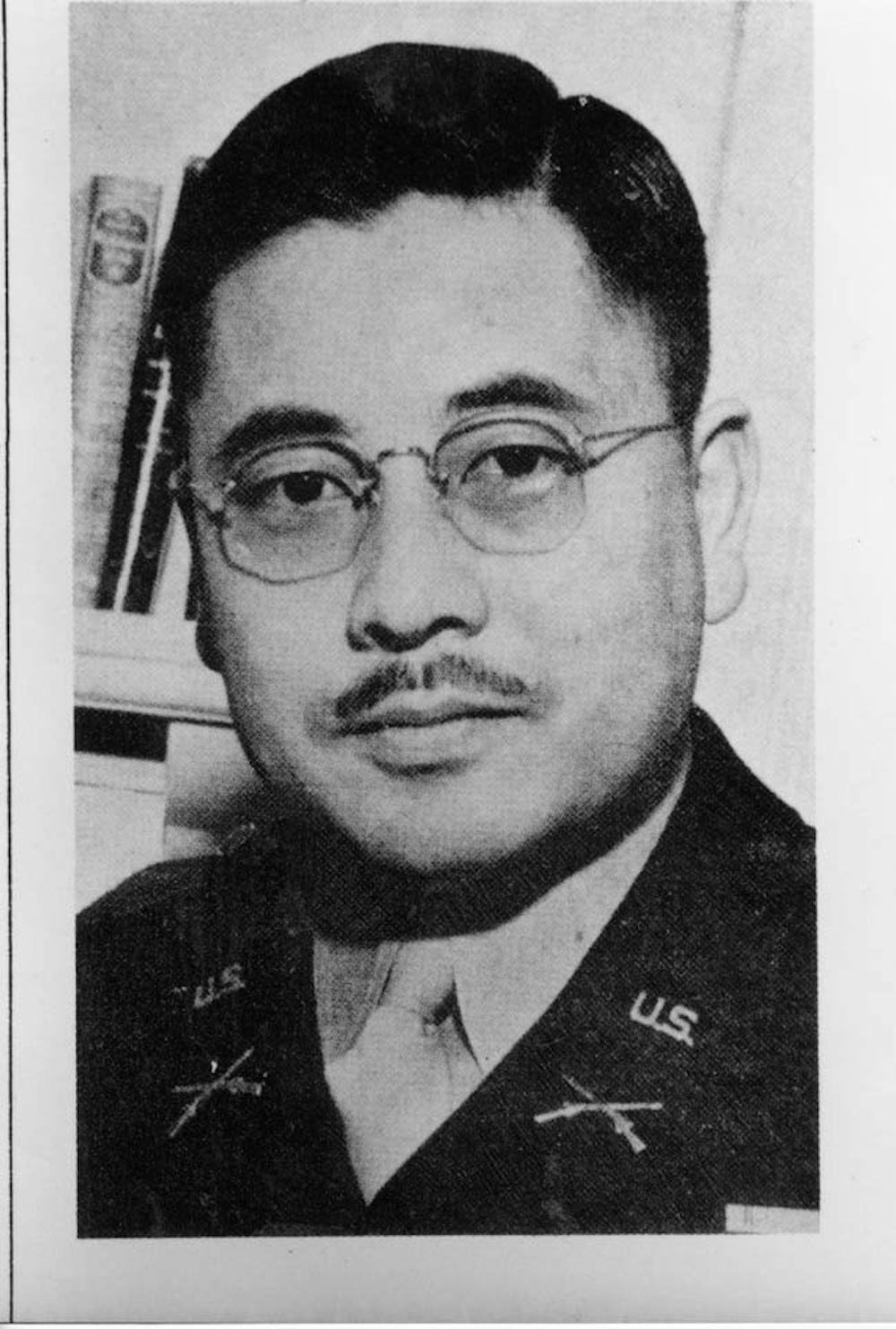

Aiso had wanted to attend an east coast university but could not afford it. After meeting with President Faunce, he was soon admitted to Brown to later become the University’s first Asian American graduate. He would later serve as the highest-ranking Japanese American in the U.S. Army and the first Japanese American in a judicial position in the contiguous United States.

Early life

Born in the Los Angeles suburb of Burbank in 1909, John Aiso routinely faced anti-Asian discrimination throughout his childhood.

“Prejudice was such a part of the environment when he was growing up in California that it was just like swimming in the water, it was part of what you encountered every day,” Eng-Wong said. Aiso ran for student body president of his junior high school in 1922, winning the election, but complaints from parents about him being a Japanese American prevented him from filling the role.

In 1926, Aiso won his high school’s oratorical contest on the U.S. Constitution, but was barred from competing in the national championship. As valedictorian, he was given a choice between giving the commencement address and competing in the national competition. The principal told him that taking on both honors was too great of a burden.

While the reason behind his forced withdrawal was never confirmed to be due to anti-Asian prejudice, Aiso admitted in an interview years later that there were multiple rumors at the time indicating as such.

This sense of prejudice was not relegated solely to Aiso’s childhood. He had to “overcome the barrier of color and stereotyping … at every turn in his life,” Eng-Wong said.

Aiso accompanied the second-place winner of the oratorical contest from his high school to D.C., coaching him for the national competition. It was there that he first met the Japanese Ambassador who had “a good friend … the president of a small but well-known New England college,” Aiso said in an interview collected as part of an oral history project at the University of Maryland. After their meeting, President Faunce secured scholarships at the University for Aiso, allowing Aiso to enroll. He majored in economics, graduating cum laude.

He followed his career at Brown by enrolling in Harvard Law School, then working at a law practice in New York for several years, before being conscripted into the army in 1941.

Wartime efforts

As it became increasingly clear in the early 1940s that the United States would be at war with Japan, the military began prioritizing Japanese language military intelligence. The government “recognized that knowing the enemy’s language could be something of value in the intelligence effort,” Eng-Wong said.

Despite many first-generation (“Issei”) and second-generation (“Nisei”) Japanese Americans being placed in internment camps during the war, some, like John Aiso, were being recruited by the U.S. Army to serve as translators in the Pacific. They employed “the same cultural knowledge” that many of their peers were being incarcerated for, Kelli Nakamura, associate professor at the University of Hawaii, told The Herald.

Aiso worked as part of the Military Intelligence Division of the U.S. War Department and soon was promoted to chief instructor of the Military Intelligence Service Language School, ultimately graduating over 6,000 military intelligence specialists during the Second World War.

In the hostile wartime climate of the 1940s, there was pressure among Japanese Americans to “justify and prove their ‘Americanism’ in very distinguished ways,” Nakamura said.

The fact that Aiso could speak and write Japanese with such fluency was “really quite remarkable” for a second-generation Japanese American, as most Nisei only “sporadically spoke Japanese,” according to Nakamura.

While facing explicit forms of discrimination in America, Aiso was not fully welcomed in Japan either, despite being ethnically Japanese. As a second-generation Japanese American, Aiso would have been labeled as a foreigner in Japan, Nakamura added.

In many ways, Aiso did not necessarily see himself as a fully integrated part of either culture, but rather as a “man without a country,” a feeling which Nakamura argues is widespread among Japanese Americans to this day.

Aiso ultimately chose to assist the U.S. military, despite having faced racism in the U.S. and being aware of the government’s Japanese internment camps. This choice was not due to a lack of conviction or strength on his part, Nakamura said, but rather a commitment to internal reform. “He wanted to do change but in a very internal way, working through the system not trying to topple the system,” she added.

According to the University’s Associate Professor of History Naoko Shibusawa, Aiso’s service to the U.S. military was separate from any of the government’s anti-Asian discriminatory actions during the war.

“You can’t identify the nation-state necessarily with the person … you can separate your love of the people from the policy of the government,” Shibusawa said.

In her interview with Aiso back in the 1980s for her senior thesis at the University of California, Berkeley, Shibusawa recalled Aiso mentioning Earl Warren’s support for anti-Asian government policies when he was Attorney General for California during the early 1940s.

Aiso told Shibusawa he believed Warren’s central role in landmark Civil Rights decisions as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court was likely due to personal regret for his previous support for discriminatory policies. Aiso believed Warren was “atoning … for his racist stance against Japanese Americans in his later acts of being so supportive of Civil Rights legislation,” Shibusawa added.

She argued Aiso’s dedication to finding something “good and redeeming” in everyone, even for people who supported racist policies against his ethnicity, made him special in the eyes of many.

Judicial service

After retiring from the army in 1947, Aiso chose a life of public service in the legal system. In 1952, he was appointed a Los Angeles Municipal Court judge — the first Nisei to hold a U.S. judicial post. Later in 1968, then-governor of California Ronald Reagan appointed him to the Second District Court of Appeal.

Aiso suffered severe head injuries in a mugging attempt at a gas station in Hollywood in 1987, tragically dying two weeks later at the age of 78.

“Sadly at the end of his life he is a victim of violence, unknown whether it was anti-Asian violence, but it makes you wonder,” Eng-Wong said.

His lasting legacy in the federal court system was something “not for personal gain” but for “the elevation of understanding what justice actually means … and to redefine what it actually means to be an Asian American,” Nakamura said.

Kana Jenkins, Curator of the Gordon W. Prange Collection at the University of Maryland, said in an email to The Herald that one of Aiso’s lasting legacies was his commitment to providing opportunities to Nisei Americans who were otherwise discriminated against or excluded.

“He really led the way for fellow Japanese Americans to be (citizens) of the United States by entering the fields where they were able to get in and where they can maintain their status,” Jenkins said.