As Da-Young Kim opened her status update in the University’s applicant portal April 6, she prepared for the hallmark of Ivy Day disappointment: a message on white letterhead that read “we regret to inform you.”

A high school senior in Montgomery County, Maryland, Kim had already “dismissed the idea of Brown” after applying to the University early decision only to be deferred into the regular decision pool. But as she opened the message, she was caught off guard by what she saw. Instead of white letterhead, it was a GIF of students holding the same sign around campus: “Welcome to Brown.”

The excitement that followed — screaming, crying, hugs and Matcha ice cream with friends — was accompanied by a sense of shock, Kim said.

“I knew there were only (so many) spots in a class they can offer,” she noted. “There’s so many terrific applicants. I had been trying to wrap my head around that.”

Getting into the University proved harder than ever this year: Out of 46,586 applicants, a record-low 5.4 percent received offers of admission, while just 3.5 percent of regular decision applicants were admitted, The Herald previously reported.

For the small sliver of applicants who were accepted, the moment was joyous and validating. But it also marked a role reversal in the admission process: After students worked tirelessly to convince the University that they deserve a spot in the incoming class, the University must now convince accepted students that they should come to Brown in the fall.

The Herald talked to eight admitted students weighing a potential future on College Hill.

For Natsinee Polvipart, an admitted student from Bangkok, the moment was akin to one “in the movies” as she cried tears of joy with her mother before she called her father on the phone, pretending to have been denied admission before owning up to the prank and letting him know that she had actually been accepted.

“I believe I started screaming,” said Bryce Vist, an admitted student from Barrington, Illinois, who opened his decision while on a Discord chat with friends. “I don’t remember much beyond that. I kept rereading it, I thought I misread it at first, I was pretty sure I had either been rejected or waitlisted.”

“I was freaking out,” said Izumi Vazquez, an admitted student from San Antonio, Texas who was also admitted to the Program in Liberal Medical Education. When she saw she had also been accepted to PLME she started crying “even more” than she had when she saw the University’s letter of acceptance

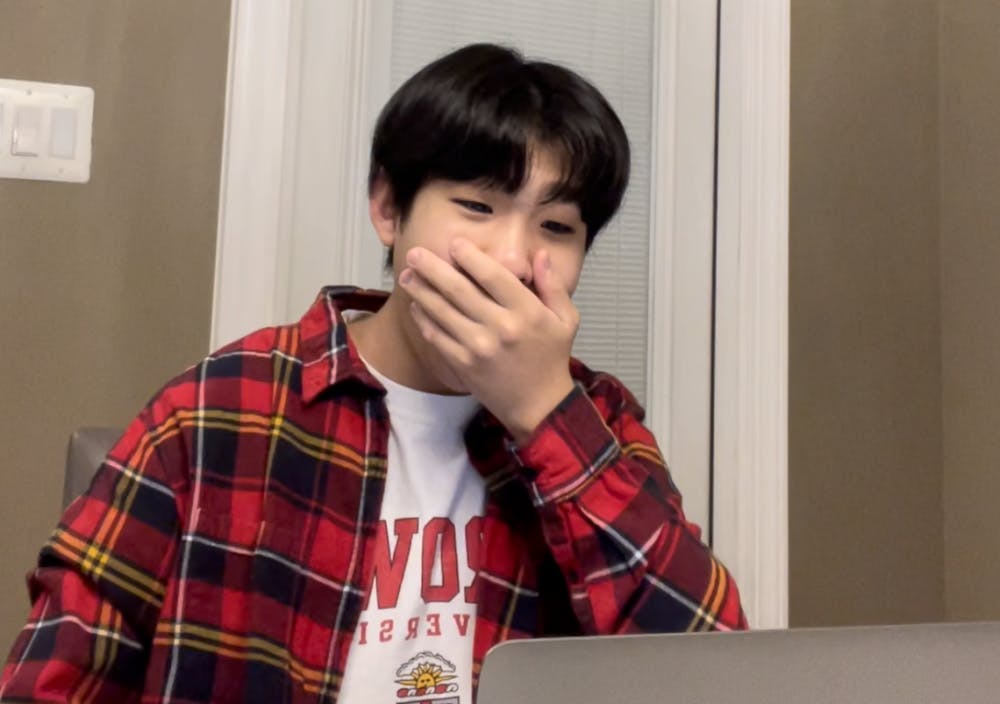

Sean Park, an admitted student from Reston, Virginia, said that “it was one of the best days of (his) life.”

“Once all that uncertainty disappears, it’s very relieving and exciting,” said Karim Zohdy, an admitted student from Prince George, British Columbia.

College admissions capped off a year of uncertainty for high school seniors, as they navigated a year online and a deeply unfamiliar in-school experience.

“After every single class, we sanitized desks and chairs. We had to wear masks eight hours a day,” Park said. “Eating lunch was weird. We weren’t allowed to face each other, we all had to face forward.”

This distance limited meaningful connection with teachers and counselors, Vazquez said.

Kurt Enriquez, an admitted student from Palm Springs, California, described his admission to the University as a “bittersweet” end to his high school years.

“California’s restrictions were really strict in my area. We had no events to commemorate my senior year,” he explained. “I’m a senior right now, but at heart I still feel like a second-semester junior.”

Admission offices across the country also changed some elements of the process, eliminating standardized test requirements and campus visits due to COVID-19. Admitted students described relying on whatever resources they could find to get a sense of the University: Instagram direct messages and Zooms with current students, YouTube vlogs, Reddit posts and official University-provided virtual tours and information sessions.

“Watching videos was how I learned about schools,” said Mahlon Page, an admitted student from Liberty, Indiana. Student-created “day in the life” videos “brought some life to campus.”

But for Vazquez, the University’s focus on digital content improved the accessibility of the admission process.

“Even without COVID, my family is not in a position where I can travel wherever I want to go,” said Vazquez, who has never been to Rhode Island. “I know that’s the case for other students — all the virtual content that’s being produced should be continued.”

Zohdy, from the western end of Canada, echoed Vazquez’s sentiment.

“I don’t think I would have been able to visit (Brown),” he added. “All of the online options to let students learn more about the University without visiting or going there really helped me.”

Admitted students added that another aspect of virtual admissions proved useful: A number of students, including Page, said they thought the elimination of alumni interviews in favor of applicant-submitted videos helped them set their applications apart.

“I really liked who I was in my video,” Page said. “I went for a very unedited approach. The ones you see on YouTube are very fancy. I talked to the camera and said, ‘Hey, this is who I am.’ I learned a little about myself as I decided what to do.’”

Vazquez thought her mix of interests — history, theater and STEM — proved her versatility to the Office of Admission as someone who could take advantage of the open curriculum.

Kim suspected that her application was strengthened by her letter of continued interest, which illustrated her investment in community-building and her efforts to create an “inclusive research design model” at an externship surrounding research regarding people who are autistic and identify as transgender.

Admitted students described their eagerness to integrate themselves into the broader University community, mentioning their excitement about public health initiatives and the Swearer Center, joining student affinity groups and publications and staking out their study spots at libraries. For others, the fall will mark the first time they’ve made it to College Hill or experienced four seasons. And, out of eight admitted students interviewed by The Herald, seven mentioned the open curriculum as a reason they were excited to come to the University.

Meeting classmates is also a point of anticipation, especially for those who have already engaged with other admitted students on social media.

“It feels like I found people who are on the same wavelength as me,” said Kim, who is on a Discord server with a number of other admitted students. “We can shift from ACE2 receptors in COVID to Toni Morrison. The thing I’m most excited about is to meet all these people from all different backgrounds.”

Admitted students have until May 3 to inform the University whether or not they plan to attend. Some have already committed, while others are weighing financial considerations — Vazquez said she sees the University as her likely choice if the Office of Financial Aid will make an offer closer to the one she received from Harvard. First-year students are able to appeal their financial aid offers and submit offers received from other institutions for comparison, The Herald previously reported

But for others, committing to the University means turning down an offer of admission from a school they like just as much or more — or potentially integrating themselves into an institution about which they harbor doubts, such as the value proposition of the cost of tuition.

“This is not a meritocracy,” Kim said. “It’s a veneer of a meritocracy, the most brilliant and smart and hard-working people don’t get into the Ivies — that’s not necessarily a prerequisite of getting into them. Is it really worth it to spend so much money for this degree, even though this school fits me?”

Enriquez, who is also considering an offer of admission to Stanford University, said he plans to determine his next four years by reaching out to current students on social media and attempting to “picture himself” at both schools.

“I want whatever school I pick to be the best pick,” he said. “There’s not a wrong choice. It’s your gut feeling.”

Will Kubzansky was the 133rd editor-in-chief and president of the Brown Daily Herald. Previously, he served as a University News editor overseeing the admission & financial aid and staff & student labor beats. In his free time, he plays the guitar and soccer — both poorly.