An unexpected snowfall closed schools in Huntsville, Alabama on the afternoon of Feb. 18. Despite the cold, NASA scientist Caleb Fassett MS’05 PhD’08 was grateful to have his two first-grade daughters home to witness a key moment in space exploration. When he was a graduate student nearly two decades before, he had hardly dared to think this day would come.

The three were glued to their TV, watching as an animated capsule glided towards Mars’s atmosphere. Jezero Crater, the place on Mars that Fassett had discovered 18 years ago, was framed on the screen by a green triangle.

“It is really exciting to go to a place that I had been thinking about for a really long time,” Fassett said. When a spot is over 150 million miles away, seeing a robot near its surface can feel intimate.

The same afternoon, Professor of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences Jack Mustard sat in his home office on a Zoom meeting with a team of scientists who seek to understand the subsurface of planets. As the capsule containing the rover neared Mars’s atmosphere, Mustard began streaming the video of the landing for all to watch. He tried his best to keep his emotions in check, just in case all didn’t go as planned.

The stress was tangible on the YouTube livestream of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab. When the capsule successfully entered Mars’s atmosphere, a team member was heard gasping “yes” over and over.

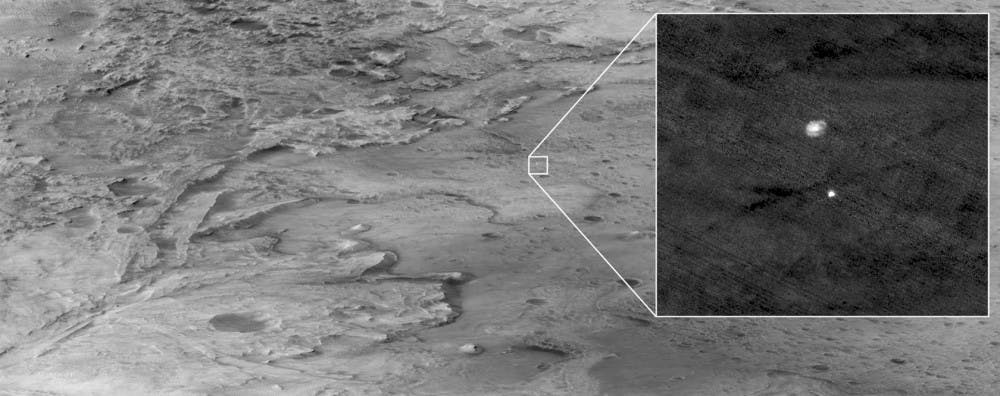

Bethany Ehlmann MS’08 PhD’10, whose research helped solidify the importance of Jezero Crater, was commentating on the landing in real time on an event with Bill Nye. As the rover parachuted into the crater for its final landing stop, a camera on board NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter snapped a photo. It’s now “her all time favorite space picture,” said Ehlmann, who is a member of the rover’s science operations team at NASA.

At 4:57 p.m. Providence time that day, NASA’s Mars Perseverance Rover touched down on the surface of the red planet.

“It was quite the moment to hear ‘touchdown confirmed’ for a site I had worked on so long and spent years poring over,” Ehlmann said.

At home in Providence, Chris Kremer GS, a PhD candidate in planetary sciences, had just woken up from a nap to a text from his dad: “Landed!”

“Were you on a plane?” Kremer wrote back, confused, then grasped what had transpired.

“I definitely felt like I had missed out on something big, but … it saved me a lot of anxiety,” Kremer admitted.

Even Brown’s veteran of space exploration, Professor of Geological Sciences James Head, mimed covering his face with his hands as he remembered watching the landing. Head has witnessed dozens of extraterrestrial landings over his more than 50-year career, and in his words, “Mars is the planet where spacecraft go to die.” After all, nearly half of the missions to Mars have failed, according to Head.

“If it had been a failure, it just would have been a huge change in our program,” Head said, thinking about the graduate students who had staked their careers on studying the region.

Jezero Crater as an exploration target

Just north of the Martian Equator lies an area comparable in size to Alaska, known as the Nili Fossae region that encompasses a Rhode-Island-sized crater formed by a collision.

Flying from South to North over Nili Fossae, a golden-orange colors the skyline, like a perpetual cloudless sunset. Below, a vast desert stretches in brown and tan. Dotting the surface are small mesa — rock deposits in the crater.

The Perseverance team compares the geology of the rover’s landing site to the Canyon de Chelly National Monument in the Navajo Nation.

University researchers have been studying the crater — once filled with water, but barren today — for nearly two decades.

From above, a channel cuts across the tan surface outside the crater. Scientists believe that the channel is a dried riverbed, signaling that water once flowed there. Starting from outside the crater and moving in, the ancient river navigates between two humps, a notch in the crater lip. Once inside the crater, it splits into many channels, forming a fan of grooves etched into the crater floor. This fan is the Perseverance rover’s primary destination: Jezero Delta.

The above descriptions of the Martian landscape come from an animation video created by Kremer in collaboration with the American Museum of Natural History. The animation is a “highly faithful” representation of what the terrain looks like from above, developed using satellite images, according to Kremer.

In 2003, Fassett, then a University graduate student in the Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences, was sitting in Head’s lab, eyeing the terrain of Mars. Since he started Graduate School earlier that year, he had been scanning data returned from the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter, an instrument drawing a precise topographic map of the planet.

Fassett still remembers the moment he spotted what looked like a sedimentary lake in the Nili Fossae region.

“I was looking at the time for places where water had modified the surface of Mars, and I remember seeing this location — it was pretty spectacular,” Fassett said, recalling his first glimpse of the Jezero Crater. “I just loved the place from the very beginning.”

Fassett brought the image to Head, who had been seeking to understand Mars’s climate, especially the nature of water on the red planet.

Head was intent on finding open-basin lakes — those with an entry and exit — because they indicate that enough water had to occupy the lake to flow out the other side. He and Fassett calculated that the Jezero Crater, formerly one such lake, likely held as much water as Lake Tahoe. When Fassett showed him the picture, though, he was struck by the clear presence of a delta — a place where a river meets a slower body of water, and the rocks the river had been carrying are deposited.

Deltas are a great place to hunt for signs of life for several reasons, according to Kremer. In the most basic sense, they once contained water, which is a key condition for life. Second, everything from the surrounding area gets washed into a delta, which would include any biological matter.

“Below the Gulf of Mexico, which (has) the richest oil fields in North America, there is an enormous delta, almost exactly of the same kind as the one at Jezero,” Kremer explained. “All the oil and natural gas that comes from the delta is a remnant … of past life.”

There are dozens of places on Mars that have been identified as possible deltas, but “Jezero is one of the few places where there is a smoking gun (that) … based on certain geologic criteria, this is a delta,” Kremer said.

Over time, the evidence for the presence of water in the delta that Fassett spotted only grew.

Head and Fassett published a research paper in 2005 on the lake, deltas and sediment that had washed into them to bring scientific attention to the area.

At the same time, Mustard, who was then soon to become a University professor with an office down the hall from Head, was serving as one of the lead investigators for a NASA spacecraft orbiting Mars — the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars — and mapping its mineralogy.

Led by Head and Mustard, researchers at Brown went on to study the composition of the crater. In 2008, Ehlmann, who was then a graduate student, used the CRISM data to pinpoint that the delta contained clay minerals, which could have preserved any biological matter from the surrounding area. With the same data, she found the minerals olivine and magnesite in the crater. Olivine transforms into magnesite in the presence of water, so the existence of them both provided stronger evidence that water flowed through the region, which Ehlmann outlined in a 2009 study.

The process of converting to magnesite can generate gases like hydrogen and methane. “A great feedstock for really simple microbes,” according to Mustard.

“Together that just said, ‘wow, this is a hot topic, man,’ you’ve got the delta with olivine and magnesite all together and a standing body of water,” Mustard said. “In terms of an exploration target, that’s huge.”