When a student visits the Brown University Herbarium, they’re greeted by countless plants meticulously climate-controlled in storage.

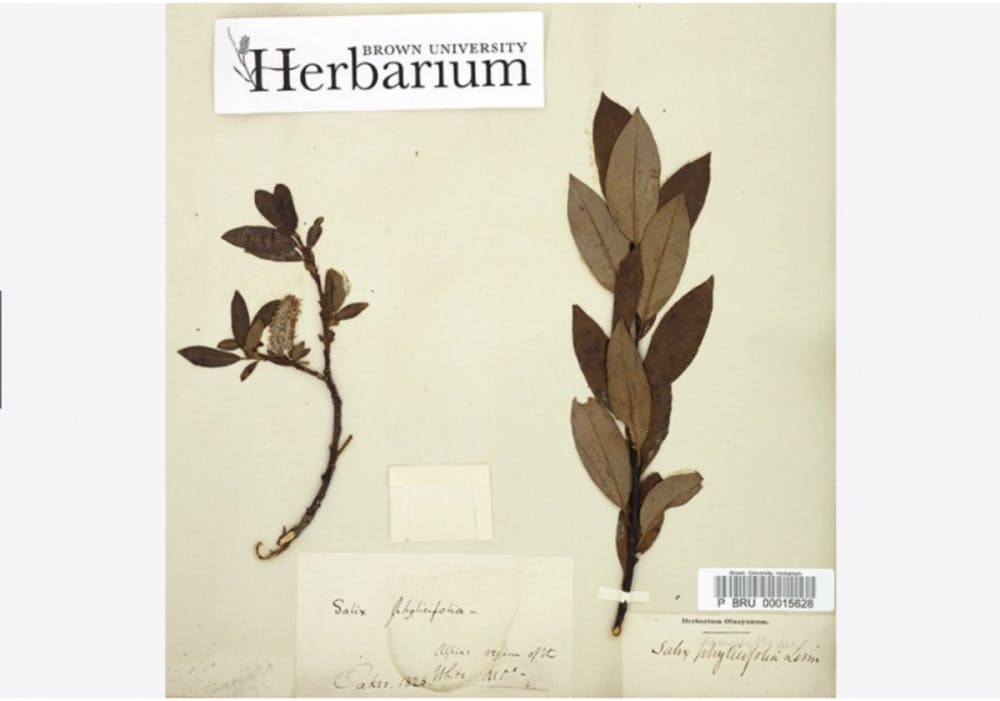

Rebecca Kartzinel, director of the Herbarium and assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, defines herbaria as “collections of dried, pressed plants, historically … used for people studying taxonomy, the study of classifying and naming new plants and identifying plants.”

But while the Herbarium holds thousands of stored specimens, from Russian wheat to Rhode Island flowers, researchers are still working to make data on those specimens more accessible for the general public.

Kartzinel, along with students and other researchers, is working to develop the HerbUX Project, which aims to make the wealth of information within the Herbarium easily accessible online. She is leading the project with Co-principal Investigator Patrick Rashleigh, who is the data visualization coordinator at the Center for Digital Scholarship.

In 1869, Stephen Thayer Olney willed his personal collection of specimens to the University, effectively founding the Herbarium. Since then, “a series of curators who also worked as professors of botany at Brown University collected for the Herbarium … and really established our collection,” Kartzinel said. Currently, the Herbarium boasts a collection of around 100,000 plant specimens from a diverse range of habitats.

The Herbarium is working on documenting “the current flora of Rhode Island to get a snapshot of what’s here now,” Kartzinel said.

Herbaria provide “physical documentations of the flora at particular places at particular times,” Kartzinel said. “If we wanted to know what was growing in Rhode Island … before there was a lot of industry here … we could go back and look at the physical specimen, confirm identification.” The documented specimens “can be used for comparison to the flora from a hundred years ago to look at how things have changed, in response to things like climate change and industrialization,” she added.

As a part of the Consortium of Northeastern Herbaria, the Herbarium’s “current goal is to make these data publicly available” by taking “high quality photographs” of the specimens and transcribing the data associated with them, Kartzinel said. Collections can be seen through accessing the Brown Digital Repository and the Consortium of Northeastern Herbaria portal.

Rashleigh and Tim Whitfeld, the previous Director of the Herbarium, began the HerbUX Project in November 2019. The aim was to make the Herbarium’s information “discoverable, meaning you can actually find what you’re looking for and sometimes, even if you don’t know what you’re looking for, you can find something that is interesting and compelling,” Rashleigh said.

Melissa Lopez ’21, a previous research assistant at the Herbarium, believes that digitizing the collections “makes the Herbarium more accessible to people who don’t have instant access.” She added that “especially now, during the pandemic, just having an online database allows anyone to learn about plants without having to physically be there.”

Though the portals are publicly accessible, “the current interfaces (do) not allow people like me to just take a look around and enjoy plants and be able to enter the plant collections without highly specialized knowledge,” Rashleigh said.

To find an object of interest on these interfaces, “a lot of times you have to know scientific names,” Carolyn Lober ’23, an undergraduate student who works in the Herbarium on the HerbUX Project, explained. The interface “puts a lot of walls of text between you and the pictures,” she added.

Hayley Uno ’20, a former research assistant at the Herbarium, has used the collections for a project in BIOL 0940D: “Rhode Island Flora: Understanding and Documenting Local Plant Diversity" in fall 2017. She identified a plant she collected, using “similar-looking plant specimens and compared them to see if they’re similar in morphology or the environment they’re collected in.”

A grant Rashleigh and Whitfield obtained from the Institute of Museum and Library Services is funding two stages: engaging the public and making a mockup of a new interface.

The first stage involves talking to “people who are the users of these plant collections, particularly users who are engaging the public or students in these collections,” Rashleigh said. In May 2020, Rashleigh, Whitfeld and Kartzinel organized meetings with three focus groups of users including science educators, Herbarium administrators and museum professionals to survey user needs.

The second stage of the grant consists of “taking the data from those interviews … and doing up a series of proposals for a better, improved interface to support those activities,” Rashleigh said. “We are looking to take the results of that analysis and turn to a design phase.”

The deadline for the user reports and mockup is November 2021, and the team is “hoping that the mockups will lead to further grants to fund development,” Rashleigh said.

Rashleigh feels that the general public struggles with plant blindness, or not having “a relationship with plants the way they do with people and animals,” he said. “Our hope is to make people feel connected and engaged with the botanical world as much as the animal world.”

ADVERTISEMENT

More