With only about 80 women imprisoned in the state of Rhode Island, should the Rhode Island Women’s Prison be closed? This question and nuances surrounding the incarceration of women in the Ocean State were explored at a Wednesday panel hosted by OpenDoors.

OpenDoors, a Providence-based nonprofit that works to support people who are formerly incarcerated when they re-enter society, advocates for reinvestment in community development and education. The Wednesday discussion was the first in a series of monthly conversations that OpenDoors is hosting to educate Rhode Islanders on topics ranging from closing prisons to decriminalizing sex work.

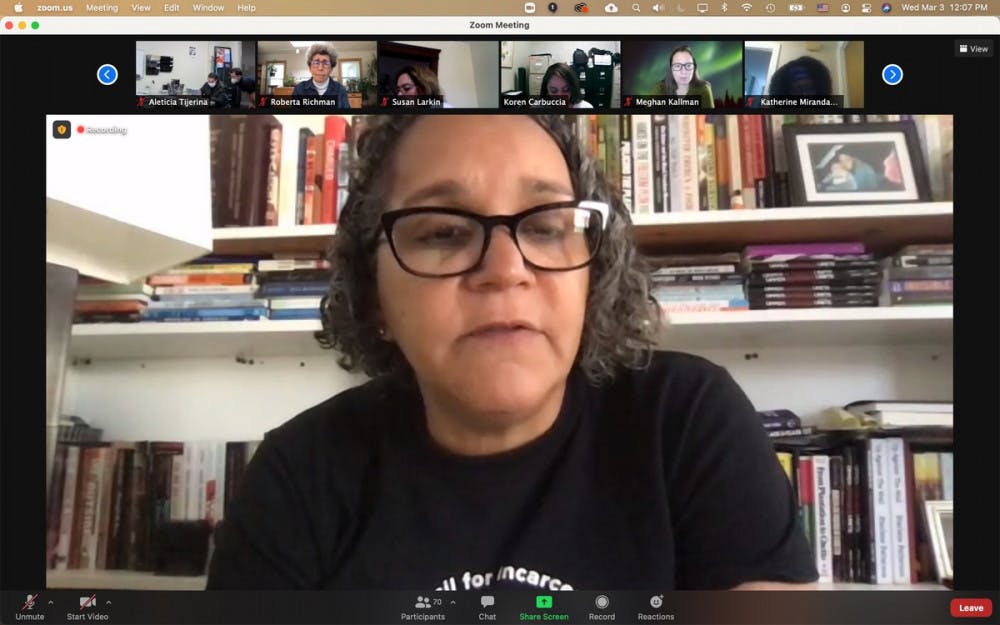

The conversation was moderated by OpenDoors Program Specialist Aleticia Tijerina and featured OpenDoors Program Coordinator Koren Carbuccia, State Senator Meghan Kallman and former Warden of the Gloria McDonald Women’s Facility Roberta Richman.

Women are deeply entangled in the criminal legal system, even if they themselves are not incarcerated, said Andrea James, executive director of the National Council of Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls.

“It is women who have held families together, raised and fed children, paid bails, sent commissary money (and) provided re-entry services,” James said.

James, who is formerly incarcerated, began the National Council with other incarcerated women in 2010 because of frustration she felt about being left out of the narrative of prison reform.

“We heard nothing about ourselves or the children, families and communities that we left behind due to our incarceration,” she said.

Since then, the National Council has campaigned and advocated for the rights of incarcerated women. On President Biden’s inauguration day, the National Council launched its #FreeHer campaign with the goal of ending incarceration for women and girls.

“The systems of oppression … still stand, but eventually they will be hollow reminders of a bygone era,” James said. She hopes that new systems will be shaped “by the experts — the leadership of women, girls and the communities most directly affected.”

Carbuccia also shared her experience with incarceration. While she was incarcerated from 1999 to 2004 for a non-violent offense, she found the most difficult part of her experience to be re-entry. Due to her criminal record, she was unable to find a job or obtain food stamps, leaving her with no way to support herself or her son.

“Walking out of the (Adult Correctional Institution) was really when my sentence began,” she said.

Carbuccia remembered the judge at her trial calling her “a menace to society.” She was a young mother, a victim of domestic violence and the caretaker of her mother, who had severe mental illness. Her experience with re-entry inspired her to work at OpenDoors to help those with criminal records get the support they need in similar situations.

Kallman spoke about Senate Resolution 245, which would create a study commission to consider the details of closing the Gloria McDonald Women’s Facility, Rhode Island’s only prison for women. The resolution is designed to be the first legal step toward the prison’s closure.

According to Kallman, research shows that the majority of women in the U.S. prison system are nonviolent, lack educational and employment opportunities and have histories of abuse. Additionally, she noted that women are much more likely than men to have children who rely on them for support.

“In most jurisdictions, women are offered much fewer programs within prisons than men are, and the services that are extensively offered in prison offer little recognition of the paths of trauma that lead folks into the criminal justice system,” Kallman said.

She also explained that the Rhode Island Women’s Facility is incredibly expensive and ill-suited to the population. There are currently around 80 women in the facility, which was originally designed as a maximum security reintegration center for men. As a result, there is a lack of recreational and programming space, as well as much higher level security than needed, according to Kallman.

Half of the women in the facility are currently awaiting trial, Kallman said, and only 23 have sentences longer than three years.

“There are currently very, very few re-entry programming opportunities for women, and there's no women's re-entry housing in the state, which is just crazy to me,” Kallman said. The state government would better support the community by investing in support for mental health and abuse and expanding diversion, parole and re-entry programming, Kallman added, encouraging audience members to advocate for change at state level.

Richman discussed her experiences as former warden of the Rhode Island Women’s Prison. She recognized that the women in the prison were victims themselves, so she sought to reform the prison by providing resources and support.

“I became immersed in a whole community of people who clearly did not belong in prison,” Richman said. “The vast majority of the people I met and came to care about in prison … were victims themselves of the crimes.”

Richman brought in counseling for victims of childhood sexual abuse and domestic violence and sought to create counseling, mentoring and drug treatment opportunities for women. She later received funding to start a transition program for women, lowering recidivism rates among participants.

“My goal really was … to provide services for women equal to what men were getting, and to allow people from the community inside the walls to see and meet and care about the women the same way I did,” Richman said.

She emphasized that the new commission would be an opportunity to make a change in the prison system. Despite having seen multiple commissions already, all with similar findings, Richman is optimistic that this commission will make a difference.

“I think this is maybe the first time that a commission's recommendations can be moved into action,” she said. “If my voice can make a difference and if I can provide some strategies or some thoughts about how that can happen, I'll be so happy.”

In the question and answer portion of the event, James stressed the importance of understanding and speaking about incarcerated women humanely. She explained that person-first language and not referring to legal transgressions as crimes is integral to individual and community accountability and healing.

“We are tired of reimagining prisons,” she said. “It's time to reimagine our communities.”

Ashley Guo is an arts & culture writer and layout designer. She previously covered city and state politics as a Metro section editor. In her free time, Ashley enjoys listening to music, swimming, and reading!