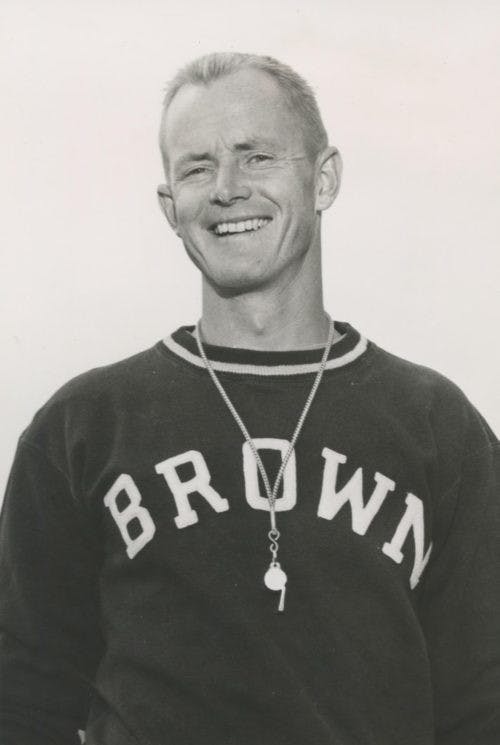

It was 1960, and Brown was trying to gain a foothold in the newly-minted athletic Ivy League. Overmatched in facilities, financial resources and athletic pedigree, one question dogged the program: Do we really belong in the Ivy League? Historically, Bruno had been an outlier, faring poorly when taking on Ivy teams, especially in the major sports. Now Brown was playing a round-robin schedule in all Ivy sports. Enter Clifford “Cliff" Stevenson, a World War II veteran who had grown up in nearby Pawtucket and had spent eight years as soccer and lacrosse coach at Oberlin College. Brown’s first full-time soccer coach, Stevenson was undaunted by the challenge, and over the next three decades, answered the lingering “belonging” question with a resounding “yes.”

After a dismal 1960 season, the dynamic and irrepressible coach quickly turned the soccer program around, winning an Ivy title three years later — only Brown’s second since formal Ivy play began in 1956. The next five seasons saw a succession of titles, including an unbeaten season in 1967. During that stretch, Stevenson’s teams ran off a string of 25 consecutive wins as Brown dominated the League.

Soon, a steady stream of talented booters arrived on College Hill, a result of Cliff’s relentless recruiting. He was not hesitant to go head-to-head with the recruiting programs of Ivy powerhouses, who had well-established relationships with key secondary schools. Cliff made it clear to these schools’ gatekeepers that he would meet with only the top student-athletes, not their second tier. His persuasive, forthright approach and ability to promote Brown as a special place was masterful. Employing a creative strategy, he often made home visits with his wife Muriel, signaling to parents that their sons would be well taken care of at Brown as extended family. Shepherding prospects through the admissions process was often an ongoing battle, with Stevenson and admissions officers at loggerheads over candidates. Stevenson’s record was exemplary, however; he did his homework and made compelling arguments to support his recruits.

As spectators began to flock to soccer games in large numbers — drawn by Stevenson’s attacking, up-tempo style of play — Cliff, ever the communicator, began to galvanize support by forming a Soccer Association at Brown. He kept everyone involved through newsletters on recruiting and other relevant soccer news. He also began scheduling games that did not overlap with football. Cliff had noticed that 11 a.m. games on home football Saturdays resulted in fans leaving for Brown Stadium at halftime. He wanted soccer to be a stand-alone event, not a preliminary football warmup.

As his teams improved, so too did the soccer field. Originally part of the Dexter Asylum farm purchased by Brown in 1957, the soccer pitch began as an unleveled, rock-strewn patch. Brown had the only soccer field in the country where after a hard rain, a soccer ball could float from one end to the other. Players from the early years remember the task of picking up stones before practice. With no field lights, late afternoon practices were illuminated by automobile headlights that lined the sidelines. Gradually, stands and fencing around the field were added, and a lighted scoreboard discarded from Meehan Auditorium was mounted on a trailer at the edge of the field. A master groundskeeper, Stevenson nurtured every blade of grass, working with Brown Facilities to create a first-rate playing surface. Permanent field lights and a modern scoreboard completed his dream facility, which was named in his honor in 1979.

Stevenson was a tireless promoter of the game at all levels, a soccer evangelist who was a pioneer in running summer camps and introducing youth soccer in Rhode Island. He was also indirectly responsible for the establishment of women’s soccer at Brown. In 1972, his daughter Karen Stevenson ’76, a first-year, asked Cliff why there was no women’s team. The result of the discussion was that Karen recruited a group of students who practiced after the men. Several players from the men’s team were volunteer coaches. At Homecoming that year, the women played a preliminary game on the varsity field against a group of older women from Pawtucket. In 1975, Brown Women’s Soccer played its first intercollegiate games. Cliff Stevenson’s visionary leadership resulted in other lasting changes to the League. He is responsible for the introduction of a standardized ball in the Ivy League, changing the practice of each school using its preferred ball in matches. He also introduced filming of games in the 1960s.

By the time he retired in 1990, Cliff Stevenson had amassed a record of 251 victories, including 10 Ivy League Titles, 13 NCAA Tournament appearances and four Final Fours. Brown soccer was a national power.

Meanwhile, Stevenson was doubling as the head coach for lacrosse, a program that had been in mothballs since 1937. After two club sport seasons, the laxers began varsity play in 1963, winning 11 games. After joining the Ivy League in 1964, the team won its first title just five years later. As usual, Stevenson was not reluctant to schedule games with the established giants of lacrosse. His 1973 team ran the table in the Ivy, after “Coach” had promised them watches if they won the title. In April, the Bruins took on number one-ranked Johns Hopkins at Brown Stadium, a contest witnessed by over 7,000 fans. By the time the program was turned over to Dom Starsia ’74 in 1983, the Stevenson lacrosse ledger included 188 victories, eight New England Championships, two Ivy titles and three NCAA tournament appearances.

Everyone who entered Cliff Stevenson’s orbit has a “Cliff story.” A few years ago, I was touring the new lacrosse locker room at the Pizzitola Center with Cliff and then-Brown Men’s Lacrosse Coach Lars Tiffany ’90. Noticing the whiteboard, Cliff grabbed a marker and began to draw up an offensive zone play for Lars. Cliff was a “lifer” who never stopped coaching.

When he retired in 1990, Cliff Stevenson had changed the culture of Brown athletics, replacing doubt with pride and optimism. He had laid the foundation for two of Brown’s most consistently successful programs, and he had remained Ever True in spite of tempting offers from other schools. He enjoyed his status as the Athletic Department’s elder statesman and go-to person.

Stevenson’s legacy is profound and is perpetuated by major soccer and lacrosse awards, as well as the Athletic Department’s annual Cliff Stevenson Award, given to "the male athlete who best exemplifies Cliff’s boundless enthusiasm, indomitable spirit and devotion to the quality of life at Brown and the surrounding community.” Stevenson has been enshrined in the Brown Athletic Hall of Fame as well as those for college soccer and lacrosse.

During his retirement, Cliff and Muriel traveled countless miles in the motor home presented to him at his Brown retirement. They often returned to New England from Florida to see former players and to revel in the open road. Cliff’s zest for life was always at full throttle. “What a country,” he would often exclaim. Always a straight shooter, in his final holiday letter to hundreds in December, he wrote: “I am 92 now … Memory a problem … I can still catch bass with my $2 lure and I can exercise on my 3 wheel electric motorized bike … I finally sold the motor home and put a little money in the bank.”

A final footnote: Cliff Stevenson watched his final sports event on Super Bowl Sunday. The next day his motor stopped running. As a youth in Pawtucket, Cliff played the three main sports of the early 1940s: football, basketball and baseball. Cliff’s son Dave Stevenson ’75, recently shared his rationale for choosing soccer and lacrosse coaching as his life’s work: “He selected two of the least-played sports at the time and wanted to grow with them.” Mission accomplished. Rest easy, Coach. We will not see your like again.

Peter Mackie ’59 is the University sports archivist with the Edward North Robinson Collection of Brown Athletics. He can be reached at peter_mackie@brown.edu. Please send responses to this opinion to letters@browndailyherald.com and op-eds to opinions@browndailyherald.com.