“Inequality. Influence. Fraud. Sabotage. These are the themes of great fiction and our modern economy,” says Amazon, the retail giant currently pressuring employees to go against unionization. Leaving a definitive footprint on the slow death-march of the publishing industry, Amazon recently released a collection of eight short stories by some of the most prominent writers today.

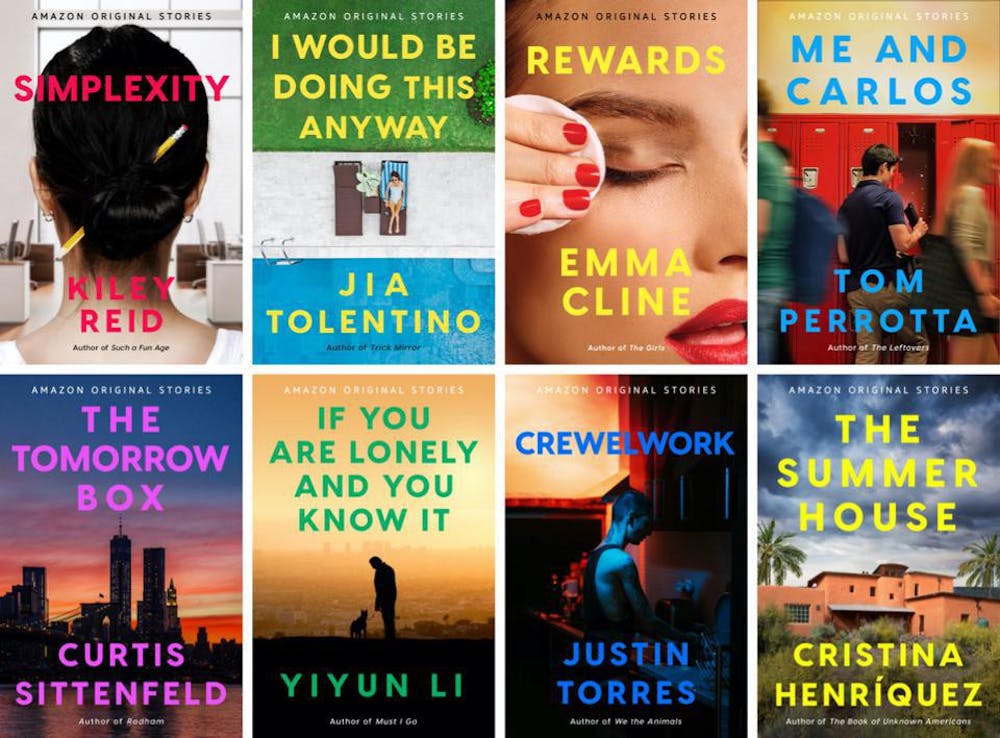

Featuring stories by authors like Jia Tolentino, staff writer for the New Yorker and author of the very millennial essay collection Trick Mirror, Curtis Sittenfeld, author of Prep and a speculative fiction novel about Hillary Clinton (Rodham) and Justin Torres, author of We the Animals, the collection is titled, without irony, “Currency.”

The authors approach the title’s theme with an Amazonian abrasiveness. Currency as sex. Currency as followers. Currency as — to be as devastatingly contemporary as this short story collection — influence.

Power is a word these writers dance around. To expressly acknowledge the contemporary impossibility of the common man grasping onto any power in a world dominated by monopolies and a few men would be to acknowledge Amazon itself. So instead, the authors settle on the effusive, digitized locus of influence.

Influence explains why half of the stories focus on fame, the most democratic of the powers, though one that applies to few. It may also explain why many of the stories deal with some sort of guilt — class guilt, white guilt, age guilt — with fear rather than introspection. Is Yumi, in Kiley Reid’s story “Simplexity,” losing her credibility with the few Black women in her office as she starts a battle they never asked her to fight? Should Tolentino’s protagonist in “I Would Be Doing This Anyway?” keep working for an insensitive, spoiled influencer, even though it feels like “pissing the bed”? By teaching “Postcolonial Perspectives,” is Andy in Sittenfeld’s story righting his wrongs as a white male? Jeff Bezos, barring apocalypse, will have power tomorrow. Yet any of the characters in these stories could be socially obliterated by one tweet. Unlike power today, influence isn’t sacrosanct. You can lose influence just as quickly as you gain it. And these characters, presumably like their authors, are determined to maintain their influence as long as they can.

This fixation on influence is the second most essential flaw of the “Currency” collection. There is nothing more important to Tolentino, Sittenfeld, Cline or Torres than influence; all transactions are influential, all losses are losses of influence. This allows for even the most banal first-world conflicts in this collection to become epic power struggles of purported importance when, in fact, they are as inconsequential as losing followers.

Tolentino’s story builds to her protagonist realizing, in the wake of the George Floyd protests, that she can’t stomach working for her employer anymore. Fine. But the dramatization of the moment (“Helicopters were circling overhead because of the protests — all protests were illegal now”) falsely suggests that this decision was rooted in anything deeper than a fear of what working for a soulless influencer could do to her social clout in the long run: its effect on her influence. Kiley Reid’s story makes note of this phenomenon through her character Yumi: “My tendency is to over-index the ethnic implications of a situation, when really, at the end of the day, wellness is wellness, you know what I mean?” Wellness is wellness, Instagram is Instagram, influence is influence. While everything is deserving of analysis, Cline’s attempt to link an experience at a beauty store to the basic “deception” of commerce in an already underdeveloped story feels disingenuous. Reading “Currency,” it feels as if Bezos ran a finger through each of the stories, marking places where an author could make another artificial reference to a social issue.

But the most essential flaw of these stories is that they are written for Amazon. No matter how good these stories could have been — and they were not good — it would be hard to stomach something that I can only read through Amazon.com, on my Amazon app or through my Amazon Kindle.

There were parts of these stories I liked. Some of them, like “The Summer House” by Cristina Henríquez, tried to deal with cold, hard power. Torres examined the guilt of succeeding as a queer, poor man. Reid’s story included a sharp account of microaggression, examining who’s allowed to be angry and when. Even Tolentino’s story, one of the weakest, maintained her familiar blunt, humorous tone. But every time a story made me laugh, AMAZON was emblazoned upon my brain. Any time a story came close to moving me emotionally, my eyes flashed to the read.amazon.com URL in my browser.

What is most ironic about these stories is that for each of the authors, currency is obviously synonymous with money, despite any attempt to glean deeper and more abstract meaning from the word. While they can dive deep into microaggressive haircuts, they fail to investigate the most prominent transaction in their writing: the one between the author and Amazon, how they managed to write about class and privilege for a corporation forcing their employees in Chicago to work from 1:20 a.m. to 11:50 a.m. or else lose their jobs. That’s the currency that’s interesting to me.

In Tolentino’s story, she acknowledges her publisher — “I was troubled about the working conditions in warehouses, we had both been ordering stuff on Amazon Prime every week” — with such frailty and obfuscation that I wonder whether she really believed she was somehow sticking it to Bezos. More likely, she thought this feeble jab could absolve her of some criticism and save her some of her influence.

ADVERTISEMENT