“Brown University, by everyone’s definition is the Ivy League brothel,” once reported the Dartmouth Review in 1986. But does Brown really stack up to this lofty reputation? And, are our hallowed, time-honored traditions safe from the puritanical tyranny of University Hall? Respectively: yes and no. A review of the Brown Daily Herald’s archives points to an extraordinarily rich history of students challenging values and norms. This culture of progressive sex and body positivity (though not without fault) blossomed due to relaxed administrative oversight — a stance that the University is presently reconsidering. As the University reviews its public nudity policies, they should do so in the interest of protecting the culture of free bodily expression and the modern-day students that participate in it.

Prehistory

Brunonia’s first brush with Playboy Magazine came in 1954, a mere year after the publication’s inception. That summer, a call for campus representatives graced its back pages. Incoming freshmen Gerald Levine ’58 answered the call, booking a December meeting with Dean Edward R. Durgin, then dean of students for the College, to arrange for the sale of Playboy on the Faunce Newsstand. Durgin was utterly unmoved, and the periodical was prohibited from the newsstand well into the 1960s. Fortunately for Levine, the college could not censor U.S. mail, and subscription commissions nicely financed Levine’s alternative meal plan of pizza and Awful Awfuls, an iconic ice cream drink hailing from Newport, through his sophomore and junior years.

In April 1957, Levine suggested to Playboy’s marketing department that the magazine host a “Playboy comes to Brown” party for his senior year. They agreed. On Dec. 12, 1957, The Herald reported that the Jameson House’s Christmas party would be sponsored by Playboy Magazine. “Jerry Levine '59 [sic], social chairman of Jameson and campus representative for the magazine, said that Playboy was contributing decorations (cartoons, playmates and a four-foot rabbit) and favors of the party.” In truth, Playboy would not be contributing playmates — the magazine offered to send one Janet Pilgrim, a three-time Playmate calendar centerfold, as his date. The promised feature in Playboy Magazine did not materialize either, although the event received coverage from Herald photographers, WBRU and Liber Brunensis.

In a letter to the editor written to The Herald, published the morning of the party, Mike Schofield '60 warned of the reputational risks of the partnership: “Life goes to Yale, Holiday to Harvard and Playboy to Brown. We’ll be the envy of the East.” Yet, for all the worry, the party appears to have been a refined affair. A Herald photograph published the following Monday depicts couples in formal attire waltzing to the live entertainment of the Tony Abbott Orchestra. And playmate Janet Pilgrim? A snowstorm canceled her flight. She instead mailed Levine her most recent centerfold, autographed and addressed to her “favorite Brown rabbit.”

University Hall’s response (or lack thereof) to Levine’s antics was our administration at its best: although Durgin declined to permit Brown to profit from sales of Playboy Magazine, he did not halt Levine from hawking the periodical, nor did he intervene to quash the Playboy-sponsored party. This laissez-faire stance — in the face of reputational risks — delegated to students the responsibility of balancing decency with sex and body positivity.

And, the limited extent to which Durgin wielded his administrative authority to suppress Playboy has aged poorly. Durgin’s newsstand ban of Playboy continued as late as 1964, when it was extended to prohibit the sale of a one-off parody of the periodical by the Yale Record. Yet, a mere five years later, Brown University was instead fighting to keep Playboy Magazine on its newsstand! On Oct. 21, 1971, The Herald reported that a member of Providence Police’s C-Squad flashed his badge at newsstand manager Fiorino DiSano, and ordered all copies of Playboy removed from public display (though it is unclear at what point the magazines were permitted to be displayed on newsstands). The move came with the signing of H1607, prohibiting the public display of publications featuring “human genitals, sexual stimulation … masturbation, sexual intercourse, sodomy … fondling, pubic regions, denuded figures … buttocks and female breasts below a point immediately above the top of the aureola” and “male genitals in a discernibly turgid state.” DiSano and Director of Student Activities William Surprenant were threatened with arrest if the violation continued. Despite this pressure, the newsstand’s Playboys were merely placed out-of-sight beneath the cashier’s counter, available by request.

⁂

From 1970 to 1973, the lounge of Perkins, originally named Gardner Hall, was rocked by the annual Streakers Ball, a party with live music, free beer and its $2 cover charge waived for anyone showing skin. Streaking was not to be confined to the Streakers Ball. The banner headline of The Herald’s March 8, 1974 issue declared “mobile lewdness rampant in R.I.” Over lunch the day before, two students dashed through the Ratty — masked but otherwise unclothed. After dinner, 400 spectators cheered on as 40 streakers “rode piggyback” around Wriston Quad, and “Streak for Jesus” signs plastered campus. Nor was streaking limited to just Brown University: Two days prior, more than 300 students streaked across the University of Rhode Island. Dean of Student Affairs, Jim Dougherty, hypothesized that the “more rigid rules and guidelines” of other institutions induced an “air of confrontation” that inspired students to streak. In contrast, The Herald reported, Brown’s streakers seemed to “streak just for the hell of it.”

But there was an air of confrontation. A letter to The Herald penned by Rob Guttenberg '75 the following week both praised streaking as a daring statement that “we are not ashamed of our bodies,” while condemning the throngs of fraternity men who “discolored its very purpose” by, for example, “simulat(ing) masturbation and fornication behind shadowed window shades.” A 1976 letter complained of fraternity brothers stumbling naked around Wriston Quad while blaring a boat horn. A 1978 police brief notes security officers finding “a number of students running naked” on the Wriston Quad after following up on a noise complaint. A 1979 letter decries the destruction of a piano and public urination by Delta Tau brothers on the fraternity’s terrace. In 1983, a police cruiser chasing a streaker down Fones Alley totaled the parked car of then-Herald Vice President Fred Brodie '84. In not one of these incidents was insufficient attire the primary nuisance.

The University’s response to such incidents was woefully both inconsistent and misguided. In the wake of the 1974 Wriston streaking spectacle, Brown administrators issued an ultimatum to the organizers of the Streakers Ball: hire Providence Police to oversee the event, or cancel it altogether. The party, which had run for three years without newsworthy incidents, was cancelled. In contrast, fraternity hooliganism went mostly unaddressed until the mid-80s. The exception proves the rule: in Spring 1980, President Swearer placed Phi Delta Beta on indefinite probation on the basis that several members were rumored to have privately engaged in consensual group sex.

Towards Modernity

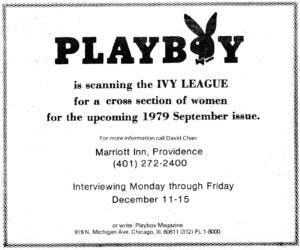

On Sept. 12, 1978, Playboy Magazine debuted an advertisement in The Herald, soliciting students to pose nude and semi-nude in Playboy’s September ‘79 issue. The advertisement sparked instant controversy. Brown Educated Women Against Rape and Exploitation, Women of Brown United, Coalition of Students Against Violence and Gay Women of Brown co-signed a letter to the editor accusing The Herald (by virtue of running the ad) of perpetuating violence against women. Soon thereafter, a Herald editorial retorted that "members of The Herald’s managing board, while not necessarily agreeing with what Playboy represents, felt that the newspaper’s readers should be allowed to make up their own minds about the magazine’s offer." Robert Reichley, vice president for University Relations, objected to the advertisement, but the University otherwise took no action against The Herald.

Despite the controversy, 150 Brown students interviewed to appear in the issue. The prospective models were thrust into a national spotlight. Laurie Osmond '81 and Cindy Cohn '80 were each interviewed by Time Magazine. Meanwhile, the controversy at Brown shifted away from The Herald’s advertising policies and onto the prospective models. On WBRU-AM’s Brown Community Forum, prospective model Amy Petronis '81 beat back against suggestions that she shouldn’t be allowed to participate. And, on Thayer Street, Petronis was reportedly accosted by a stranger who accused her of making streets unsafe for women to walk.

Ultimately, six Brown women were selected to pose in Playboy’s September issue. In an interview with The Herald, model Laurie Osmond '81 summarized the shooting process as “relaxed” and concluded: “I really enjoyed myself.”

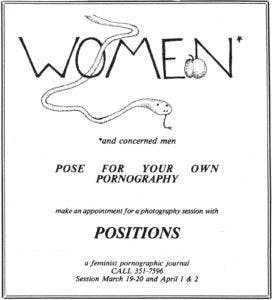

The Playboy affair marked the beginning of the modern era in body and sex positivity (and backlash) at Brown, in which students exercised agency over their bodies and engaged in fruitful discussion amongst themselves about its ramifications. That’s not to say Playboy’s 1986 return to Brown University was no less controversial — inviting equally acerbic letters to The Herald, and inspiring a protest outside the photographer’s hotel. But it was just as fruitful. Simultaneously, Heather Findlay Ph.D. '86 and Miven Booth '87 launched Positions, a hard-core feminist foil to Playboy, conceived “as a creative departure from what we saw to be a no-win discussion among feminists over censorship, free speech and pornography.”

Playboy’s detours to Brown University were a reliable catalyst for insightful campus discussions. For instance, Playboy’s 1995 detour to Brown University sparked one letter that considered how widespread internet access changed the risks of posing for the magazine, and an article interrogating why on-campus recruitment by the United States Armed Forces was permitted, but on-campus recruitment by Playboy was not.

Present Era

In the present era, students’ opportunities to explore nudity have been of their own making. In lieu of the Streakers Ball, Brown students organized the invitation-only annual naked parties at the Watermyn and Finlandia co-ops throughout the 1990s and 2000s. Members of the Brown University Naked Society now host naked parties and carpools to Dyer Woods, a nudist campground and nature preserve in Foster, Rhode Island.

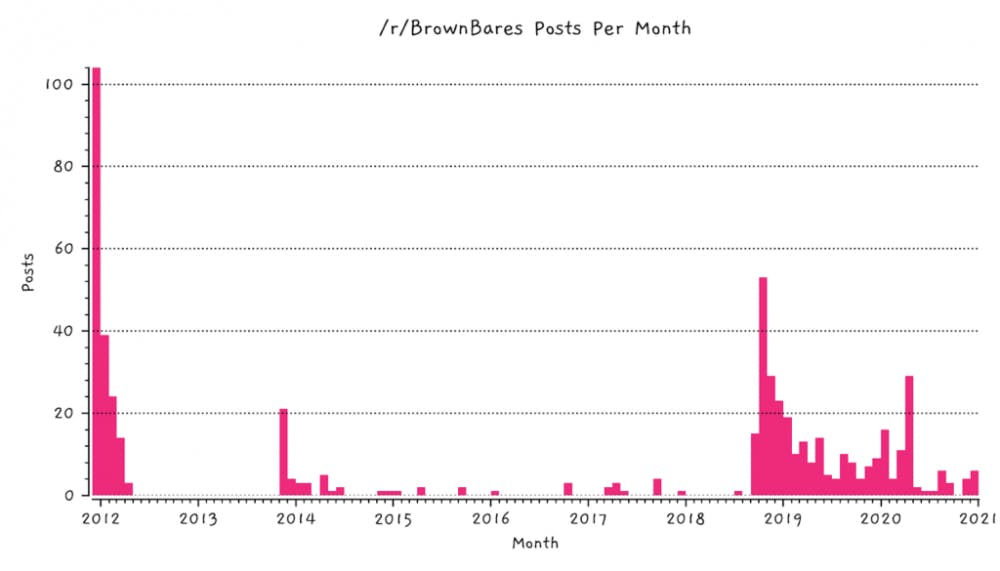

And in the spirit of Positions, Brunonians have long leveraged the internet to seize the means of nude publication for themselves. Since 2011, at least 215 Brunonians have bared it all on /r/BrownBares, a subreddit where students post their own nude photographs.

Nine years after its creation, /r/BrownBares still attracts a steady stream of bold-and-bare Brunonians.

Since 2012, Nudity in the Upspace has annually provided a week-long panel of nude events, aimed to destigmatize nudity, such as nude yoga, nude body painting and a nude discussion panel.

And, for those already comfortable in their birthday suits, the Naked Donut Run nears its 30th anniversary of streakers passing out donuts and munchkins to students studying for finals. Its organizers have mindfully balanced preserving the tradition with respecting those who would rather avoid the event, advertising “nudity-free zones'' ahead of each run. The particulars of its measures evolve and improve with every semester.

Uncertain Future

For nearly 70 years, the Brown community has experimented openly with its nudity and sexuality — buoyed by a community culture that values intense interrogation of its place in society, and relaxed administrative oversight that has largely left these discussions up to the community.

However, the latest report of the Committee to Review the Code of Conduct places this tradition in peril. The report described that the committee considered prohibiting public nudity, but deferred on the decision due to “concerns about some of the political implications of such a decision.” The committee instead recommends the adoption of a University-wide nudity policy for the next edition of the Code of Conduct.

In the past 30 years, Brown University students have demonstrated that they can conduct themselves maturely in matters of public nudity. The 1970’s scourge of unruly streakers is nearly a half century in the past — and even then, attire (or lack thereof) was really not the primary nuisance. Issues of sexual exhibitionism are already covered by two University-wide policies against sexual harassment: The Code of Conduct and the Title IX policy, which in part prohibits the creation of an environment considered “intimidating, hostile or abusive.” So, what need could a new policy fill?

The issues of public nudity faced by Brown University, are, in fact, issues facing its nudists. Brown University’s contracted security guards, unaware that public nudity is not prohibited at Brown University, often accost the runners. In December 2010, SciLi security guards halted the NDR, demanding the personal information of runners so that they could be identified on security camera footage and threatened to call the police. In Fall 2019, security guards at the SciLi once again stopped the run until the Brown University police confirmed that the tradition was permitted, an organizer of that run told me. And, despite the precautions of the run’s organizers, there have invariably been students wielding camera-phones — reminiscent of how the fraternity brothers of the ‘70s harassed streakers on Wriston.

To the extent that Brown University is in need of a policy on public nudity, it would be a policy that clearly affirms students' right to recreational nudity, free from harassment. Such a policy could protect the safety of the NDR’s participants, and preserve the community’s autonomy to self-regulate recreational nudity. Instead, Brown seems poised to repudiate recreational nudity. At worst, this could draw the tradition of the NDR to a close. At best, it would stagnate the NDR’s ability to evolve to meet the needs of campus. In any case, it would mark the end of Brunonia’s grand, naked experiment.