The Title IX and Gender Equity Office released its 2019-20 Annual Outcome Report Dec. 10, revealing a slight increase in the reported incidents of sexual misconduct at the University.

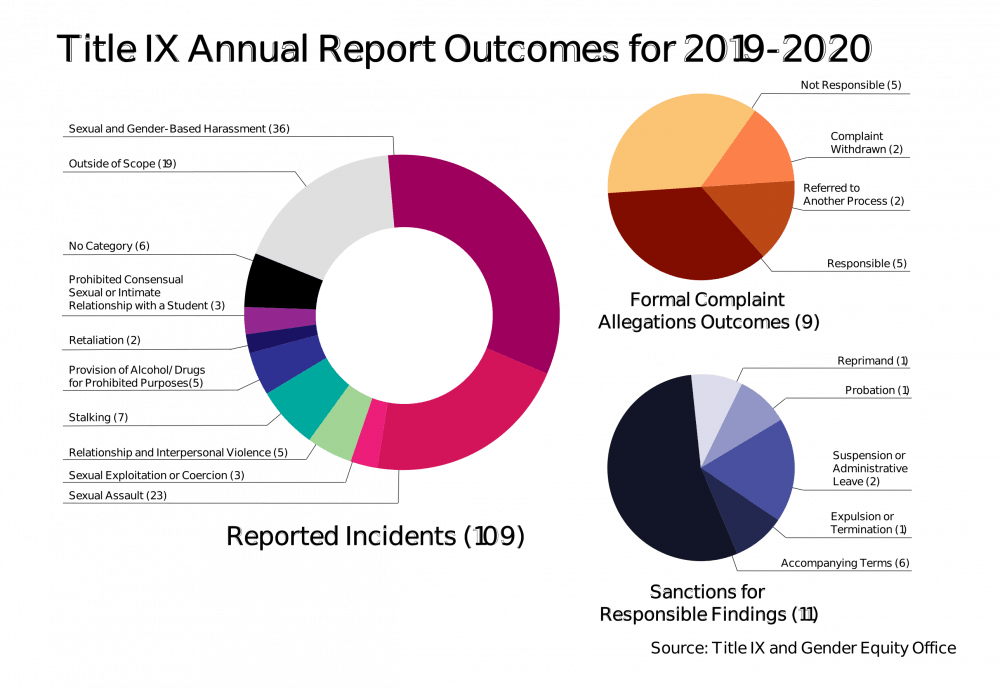

There were a total of 109 allegations made in the reporting window of July 1, 2019, to June 30, 2020, in comparison to 104 allegations in the 2018-19 report.

The data captured in the report are related to conduct forbidden under Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, federal legislation that prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in educational programs and settings. The University made revisions to its existing Title IX policy in response to new federal guidelines that went into effect Aug. 14 of last year. These changes include enforcing a higher standard of proof for allegations, limiting the kinds of cases upon which colleges and universities must act and requiring live hearings for cases of sexual misconduct, The Herald previously reported. These updated regulations did not affect the information in the Outcome Report, which predates the enforcement of the Title IX policy revisions.

According to the report, the University is in the process of drafting a new policy to address sexual and gender-based harassment and sexual violence that does not fall under Title IX.

The uptick in alleged misconduct might reflect a better use of and increased comfort with channels for reporting misconduct rather than an actual increase in instances of prohibited behavior, the report stated. The report cited a survey from Oct. 2019 in which student respondents reported an increased trust in the University’s resources surrounding sexual misconduct relative to 2015.

But offical data from the Title IX office only reflect a portion of actual instances of sexual assault at Brown, according to informal survivor data collected by Amanda Cooper ’22 and Carter Woodruff ’21.5, along with their fellow members of Voices of Brown, a public Instagram account that features student-survivors’ anonymous stories of sexual violence.

Instances of sexual assault reported in the optional and anonymous 2019 Association of American Universities Campus Climate survey conducted at Brown were higher than those reported to the Title IX Office, Cooper and Woodruff said.

“It makes total sense to me that there would be a discrepancy between reporting rates due to the various obstacles that survivors face when trying to seek justice,” Woodruff said. “If Title IX were made more accessible and understandable to the student body, I’m sure reporting rates would go way up.”

Breaking down the data

The report provided information on the University’s sexual misconduct complaint processes, the outcomes of these complaints and whether or not they resulted in sanctions such as a reprimand, suspension or expulsion. Only one student received the expulsion penalty as the outcome of the University’s complaint process.

Ten complaints were processed through the University’s official complaint procedures for complainants who requested an investigation. Following the investigation of allegations within nine formal complaints, five respondents were found not responsible, five were found responsible and two were referred to another process. Two complaints were withdrawn during proceedings.

The University’s Title IX policy allows complainants and respondents to appeal outcomes on the basis of substantial procedural errors, new material evidence and decisions or sanctions that are contrary to the weight of the evidence in cases involving a student respondent. Last year, two appeals were submitted to the University.

The report also offered insight into the informal resolution process, which allows parties to put forth terms of resolution that they see as an appropriate outcome to a given complaint. Through this informal channel, participants are not required to communicate directly with one another or undergo an investigation, hearing or finding procedure. Two complainants and respondents chose to resolve their complaints through informal avenues.

The prohibited conduct highlighted in the Outcome Report was broken down into several categories: 36 incidents of sexual and gender-based harassment, 23 incidents of sexual assault, three incidents of sexual exploitation and sexual coercion, five incidents of relationship and interpersonal violence, seven incidents of stalking, five incidents involving the provision of alcohol and/or other drugs for purposes of prohibited conduct, two incidents of retaliation, three incidents of prohibited consensual or intimate relationship with a student, 19 incidents of conduct outside of the scope of the Title IX policy and six incidents falling under the “unable to categorize” umbrella.

Behavior that falls outside of Title IX’s purview “often involves reports with perpetrators who are unaffiliated with Brown, or the behavior reported is not listed among the prohibited conduct in the Sexual and Gender-Based Harassment, Sexual Assault, Relationship and Interpersonal Violence and Stalking Policy,” Title IX Program Officer Rene Davis wrote in an email to The Herald.

For such conduct that falls outside of Title IX’s scope, incidents are channeled to other campus resources, such as Campus Life, academic departments, deans or staff supervisors, Davis wrote.

Encouraging reporting

The Title IX Office engages in a variety of steps to encourage reporting cases of misconduct. “I have taken multiple opportunities to speak to students to de-stigmatize concerns associated with reporting,” Davis wrote.

Davis is working with student governance and survivor activist groups to respond to questions and concerns surrounding reporting, as well as with colleagues in offices working directly with survivors: the Sexual Assault Peer Educators, Women Peer Counselors and Sexual Harassment & Assault Resources & Education advocates.

“These individuals provide important insight and can also clarify myths associated with reporting in their own work,” Davis wrote.

As part of its advocacy work, Voices of Brown has partnered with Brown’s chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union to comb through the University’s Title IX policy, with Davis’ help, and break it down on the group’s Instagram page to make the information more accessible to the community, Cooper said.

The Outcome Report highlighted the past year’s training and community education efforts related to Title IX, which “focuses on education, intervention and accountability,” Davis wrote. “We put an emphasis on education and awareness to influence attitudes, which the research shows will lead to changes in behavior.”

During the reporting window, the BWell Health Promotion Office conducted 130 workshops and training sessions for more than 5,000 new and returning undergraduate, graduate and medical students with the goal of educating students on their obligations under Title IX. Brown’s Sexual Assault Peer Education program also held 63 workshops reaching 743 participants in the community.

Both Cooper and Woodruff noted that most of these modes of training consist of optional workshops, with little oversight from higher-ranking University administrators. The training that is mandatory, other than basic consent training first-years receive, is usually punitive, Woodruff added. She and Cooper feel that regular conversations and trainings surrounding sexual violence should be a mandatory part of students’ experiences during their four years at Brown, even potentially showing up on their transcripts.

The Future of Title IX

Both Woodruff and Cooper commended Davis on the work that she and her office, as well as the campus SHARE advocates, perform to support survivors within the Brown community. Still, they expressed concern that higher University administrators are disconnected from the work that is being done by more specialized offices and roles.

Woodruff also argued that the language of the report, which affirms that preventing and addressing sexual harassment on campus is a “priority” for the University, is inaccurate.

“We’re not going to end sexual violence by hiring one amazing person and having them do all of the work that the administration should be pouring money into and having a whole team dedicated to doing,” Woodruff said.

For survivors like Woodruff, witnessing the University’s effective response to the COVID-19 pandemic has been strangely disappointing. “They know how to tackle a public health crisis, one that is related to seemingly uncontrollable social scenes at Brown,” she said. “They know what to do when there’s an epidemic on campus, but they’re not treating the epidemic of sexual violence at Brown as the health crisis and safety crisis that it is.”

Cooper echoed the sentiment. “Sexual violence leaves scars that nobody sees,” she said. “There are so many lingering repercussions of these actions, and the fact that perpetrators are not being caught and there are low numbers of reports all feeds into this problem.”

“When (Voices of Brown) was first founded, in the first few weeks, we were getting DMs upon DMs from survivors at Brown who needed urgent assistance,” Woodruff recalled, while reflecting on the lack of accessibility and trust in formal Title IX procedures at Brown. “Title IX is really not the end-all-be-all and shouldn’t be, and we’re seeing vast negligence at the higher up administrative level and historic negligence.”

With the impending presidential inauguration, Davis and her colleagues keep an eye toward potential policy changes that might accompany the new administration. “A change in presidential administration could bring changes in federal guidance, and Brown will certainly follow any developments closely,” she wrote. “We would revise our policy and procedure to comply with any subsequent changes in the law.”

ADVERTISEMENT