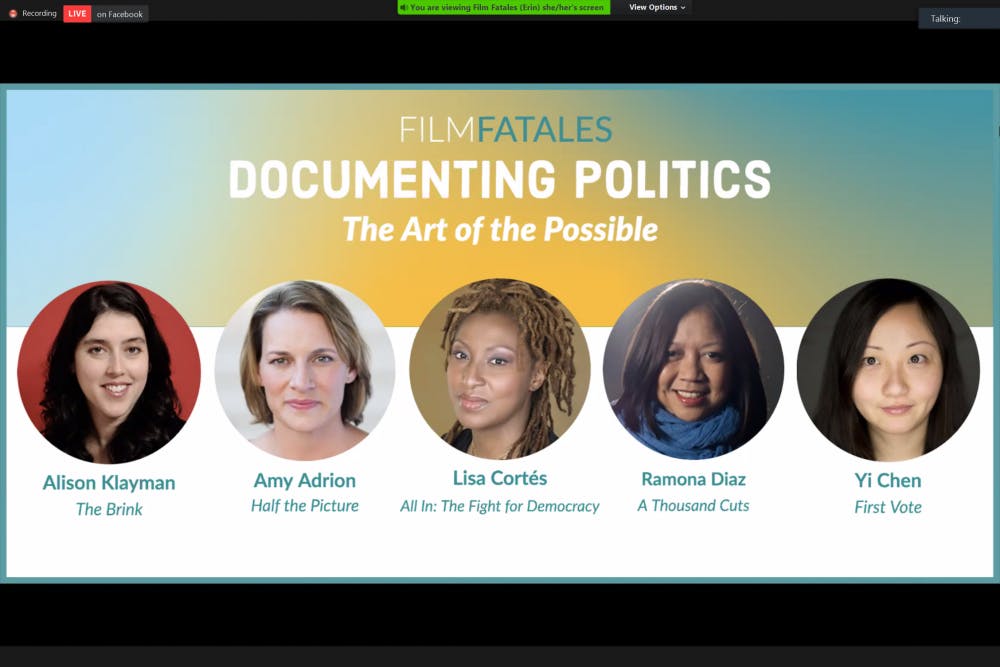

Non-profit organization Film Fatale and Leah Meyerhoff ’01 of the Brown University Entertainment Group, an alumn Facebook group, co-hosted a webinar Friday evening entitled “Documenting Politics.” The event, presented by non-profit organization Film Fatales, invited influential female filmmakers for a timely discussion on their recent political documentaries.

Filmmaker and moderator of the event Amy Adrion introduced four women filmmakers on the panel, describing their most recent works as “uncannily timely” in light of recent events in the United States and the world at large.

Each of the films examines “political thought leaders and movements, the power of democracy, the attraction to populism and voting patterns that defy simple gender, racial or economic stereotypes,” Adrion said.

After her introduction, each panelist had the opportunity to speak about her own film and answer questions from both attendees and other panelists.

American film producer Lisa Cortés discussed her film “All In: The Fight For Democracy.” The work focuses on Georgia politician and voting rights activist Stacey Abrams and her efforts to confront voter suppression and democratic irregularities after losing the 2018 gubernatorial race in her home state of Georgia.

Despite Abrams’ eventual loss in 2018, Cortés found a “success story” worth documenting. Abrams followed her loss by increasing Democratic voter participation in the state, and many have credited Abrams for President-elect Joe Biden’s success in Georgia.

In the film, Cortés also sought to acknowledge other organizations seeking to combat voter suppression in the state of Georgia, including the New Georgia Project, Black Voters Matter and the American Civil Liberties Union. These organizations were all part of the “coalition” dedicated to “making certain that the seat at the table became expansive for communities that traditionally had not felt welcome there,” she said.

Documenting the other side of the aisle, filmmaker Alison Klayman talked about her film “The Brink,” which follows the life, travels and exploits of President Trump’s former campaign manager Steve Bannon in the years after the 2016 election.

Klayman spent 13 months filming with Bannon, from the time he left the White House to the 2018 midterm election.

At that point in Bannon’s life, he was “enjoying the most fame, the most success, the most power he had ever had in his life due to a brief stint with the Trump campaign.”

Klayman wanted to observe what his next steps would be.

“I wanted to be in those rooms. I wanted to see what was going on,” she said. “He was enough of an egomaniac that I saw … from our first meetings,” and she wondered if “his hubris could be his downfall.”

Adrion thought that the documentary was “a fascinating portrait” of the former campaign manager. “He doesn’t come off seeming that unlikable, even knowing who he is, and what the policies are,” she added.

Figuring out how to properly cover far-right groups — which are sometimes misrepresented by the media — is often difficult, Klayman said. “As journalists,” she said, “we have to get sharper about how we engage with, understand and oppose these elements.”

Taking another angle at American elections, Yi Chen spoke about her documentary film “First Vote,” which followed four Asian Americans in battleground states North Carolina and Ohio as they cast their first ballots in 2016.

In the film, Chen emphasizes that the Asian-American vote is not a monolith. “The four voters in the film actually have very different backgrounds,” Chen said.

Two of the subjects of Chen’s movie, Sue and Lance, are Chinese immigrants. Both had supported democratic candidates in the past, but resonated with Trump’s message in 2016. The other two subjects, Kaizer and Jennifer, were born in the United States. After living in Beijing for 16 years, Kaizer moved back to the United States, deliberately choosing North Carolina to live in a battleground state. Jennifer, a critical race theory professor at UNC Chapel Hill, has always been a Democrat and even campaigned door-to-door for the Democratic Party in 2016.

Ultimately, the goal of Chen’s film is that “audiences … will walk away with a more nuanced and deeper understanding of the Asian-American electorate,” she said.

Ramona Diaz closed the panel conversation by talking about her documentary “A Thousand Cuts,” about Rodrigo Duterte, populist president of the Philippines, and journalist Maria Ressa, who has investigated him.

Duterte rose to power following the fall of the dictatorship under Ferdinand Marcos in 1986. Promises of prosperity were left unfulfilled in the post-dictatorship time period for some, “which made Duterte very attractive,” Diaz said.

“He portrayed himself as some kind of outsider,” she said. “He campaigned on a drug war. He said ‘It will be bloody, there will be bodies in the streets.’ But still he was voted into office.”

When asked what drives support for Duterte, Diaz said, “The same question could be asked here, right? What drives support for Trump?”

Ressa started uncovering Duterte’s exploits through her digital newspaper company Rappler. “They started questioning the drug war … the numbers … impunity. Why is the president getting away with this?” Diaz said. “Because of that, (Ressa) became the target of Duterte’s ire,” she added. During her investigation of the president, she was arrested twice and detained once. “She started questioning Duterte when no one else was,” Diaz said. “Not only did she question the drug war, but she connected the drug war to misinformation and the weaponization of social media, which sounds familiar,” Diaz added. Interrogating how governments use social media is important to Diaz as “this violence doesn’t stay online. It jumps to the real world,” she said.

“That’s why I think people gravitate to her,” she said, “because they’re reminded of their best selves.”

To conclude the talk, all filmmakers were asked what they seek to accomplish through their films, how they view their jobs as filmmakers.

“It’s a privilege to have a front seat to history,” Diaz said. “My job as a filmmaker is to give you an experience of something that I find fascinating, and hopefully you find fascinating. It’s appropriate to have more questions than answers at the end of these films,” she added.

Filmmaking “allows me to be an observational interrogator,” Cortés said, regarding her own work on Abrams. “Of history, culture and the delicate thread that holds it all together. And then see where we can start to pull that thread on the road to freedom and liberation,” she added.

“I really hope that this film will start a conversation and bring more attention to understanding the power and diversity of the Asian American electorate,” said Chen.

“Everything is political. …I always hope to leave people asking questions, better questions, more questions. It’s journalism and culture, it’s art and history,” Klayman concluded. “You get to ride shotgun on someone else’s life for a little bit. I don’t know if my films point people to do a certain thing, but I hope to leave people with new questions — better questions.”

ADVERTISEMENT