Democratic political donations from University employees have increased exponentially since 1992, dwarfing donations to Republicans, which have more or less remained constant, according to data from OpenSecrets.

In 1992, 32.5 percent of total political contributions from Brown community members went to Republicans. In 2020, however, just 0.8 percent of total political contributions went to the party, according to the data.

OpenSecrets’ data only includes faculty, staff and students who listed Brown University as their employer.

One likely reason for the most recent spike in Democratic donations is “a reaction to the chaos, mismanagement, corruption and racism which have marked this president's four years of governing,” according to Richard Arenberg, visiting professor of the practice of Political Science and interim director of the Taubman Center for American Politics and Policy. He said that while Brown voters typically lean more Democratic than the broader population, the recent trend reflects a reaction to Trump, rather than simple ideology.

In 2020, University employees donated almost $160,000 directly to the Biden campaign and more than $57,000 to Sanders, according to OpenSecrets. Only $366 went to Trump’s campaign. In 2016, Trump received $40 from University employees — far less than Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz.

Still, Arenberg said he does not expect donations to fall dramatically in the next election cycle because of the explosion of small political donations, which he credits to the rise of fundraising sites like ActBlue.

Since the start of 2019, more than 14,000 donations have been made to ActBlue from Brown employees, according to data from the FEC.

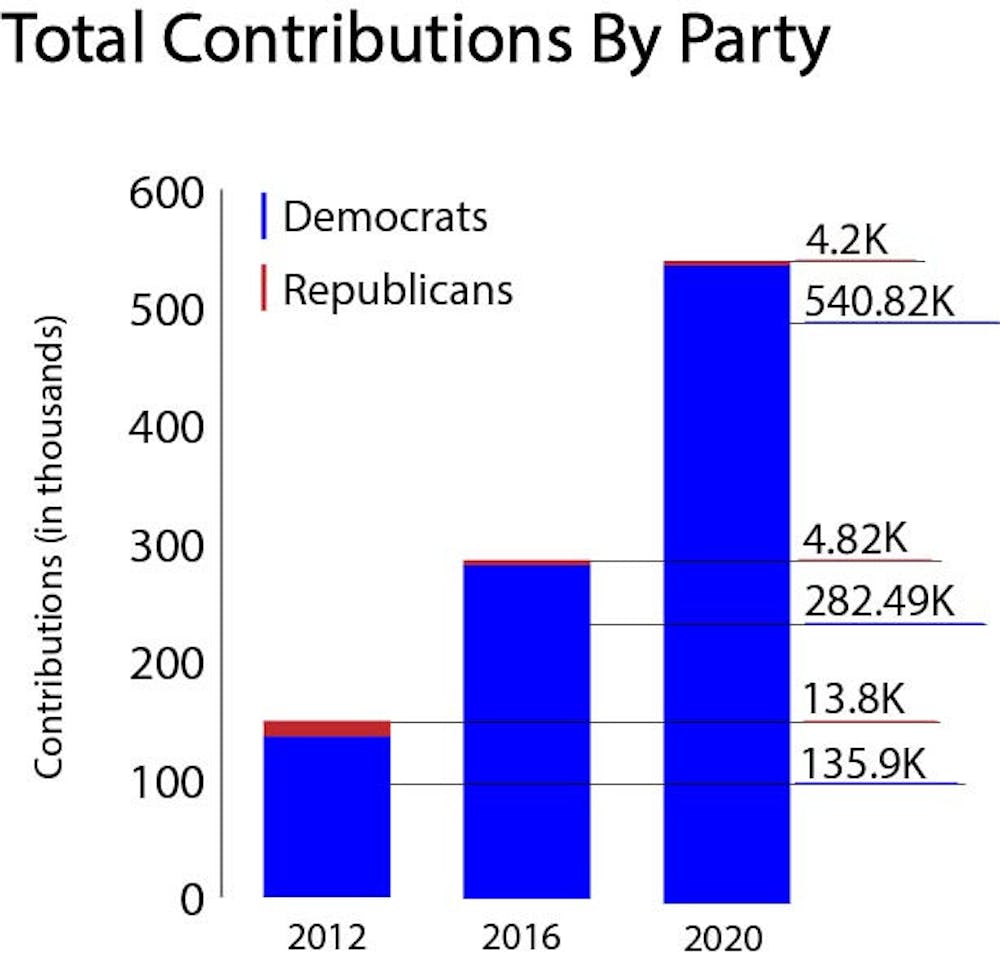

Ballooning University-affiliated Democratic donations have fueled a large overall increase in donations. Total recorded donations from University employees rose from about $150,000 in 2012 to around $293,000 in 2016 and around $561,000 in 2020, according to OpenSecrets.

This increase reflects recent national trends. The 2020 election has shaped up to become the most expensive campaign in American history, hitting double the previous record set during the 2016 election, according to the New York Times. Congressional campaign spending has been steadily rising for decades, and twice as many Americans made political donations in 2016 than in 1992, according to the Pew Research Center.

Jon Nelson GS, who has used ActBlue since 2016, said he began donating because the past few elections have put politics “profoundly out of whack.” He hopes his donations help to “right the ship” of American politics.

Economic theory has “a lot of trouble rationalizing voting and donations,” said Associate Professor of Economics Gauti Eggertsson. “You're exerting effort to go vote or donate, and your chances of being pivotal is essentially zero.”

Still, Eggertsson donated several times to the Biden campaign this year. He said that Trump’s reelection could have “very bad long-term consequences” on the country’s alliances with other nations and with free trade agreements. His donations were also spurred by concern for the continued “viability” of democracy in the U.S. and the administration’s “lack of respect for normal, fact-based discourse.”

Only two University employees have donated directly to Trump’s campaign in the past three years, and a third to the Republican National Committee. One of the Trump contributors is Eric Anderson, a lead developer in Computing and Information Services who, by his account, leans libertarian. “I'm a conservative who lives in Massachusetts,” he said. “Politically, I never get what I want.”

While Anderson added that he is not “particularly fond” of Trump’s behavior, he decided to donate to the President’s campaign because of his judicial nominations and tax cuts.

Anderson said that left-leaning political ideology is often noticeable on campus but has never been a personal issue for him. “I'm not interested in telling people how to live their lives,” he said. “Regardless of how they feel about various issues, we're still friends and family. There's more to life than politics.”

Still, Anderson said that a politically insulated campus, like any “homogenous” population, can create “caricatures” of those outside of that bubble. He believes open conversations that allow for “the free flow of ideas” can alleviate this issue, but that the pandemic has made communities such as Brown “more disconnected now than ever” before.

Anderson sees the national rise in political donations on both sides as a reflection of political polarization. “What do we usually do when we're in situations where people can't hear each other? We turn up the volume. Political donations are (a way of) turning up the volume,” he said.

Arenberg, on the other hand, views the increase in donations as a “positive indicator,” which reflects “the greater overall interest in, commitment to and involvement in politics and policy by the Brown community.”

ADVERTISEMENT