Instead of relying on only a physical barrier, what if scientists were to develop a substance capable of killing COVID-19’s viral particles when they come in contact with personal protective equipment? And in cases where the virus evades these protections, what if programming software could give radiologists an extra set of eyes when diagnosing the disease?

Among the engineering-based, University-researcher-led projects set into motion by the COVID-19 pandemic, two have sought to answer these questions in recent months. These projects, which received a kick-start from the University’s COVID-19 Research Seed Fund, arose from collaborations between University researchers, a transnational company and state hospitals.

A silver lining

Personal protective equipment once filled the shelves of storage rooms in hospitals and other potentially hazardous workplaces in full stock. But in the wake of COVID-19, boxes of face masks started to empty just as these supplies became an imperative addition to people’s wardrobes.

As masks have become a mainstay of outings and extra PPE has become necessary in situations where social distancing cannot be maintained, industries and researchers have joined forces to improve the protection these materials offer.

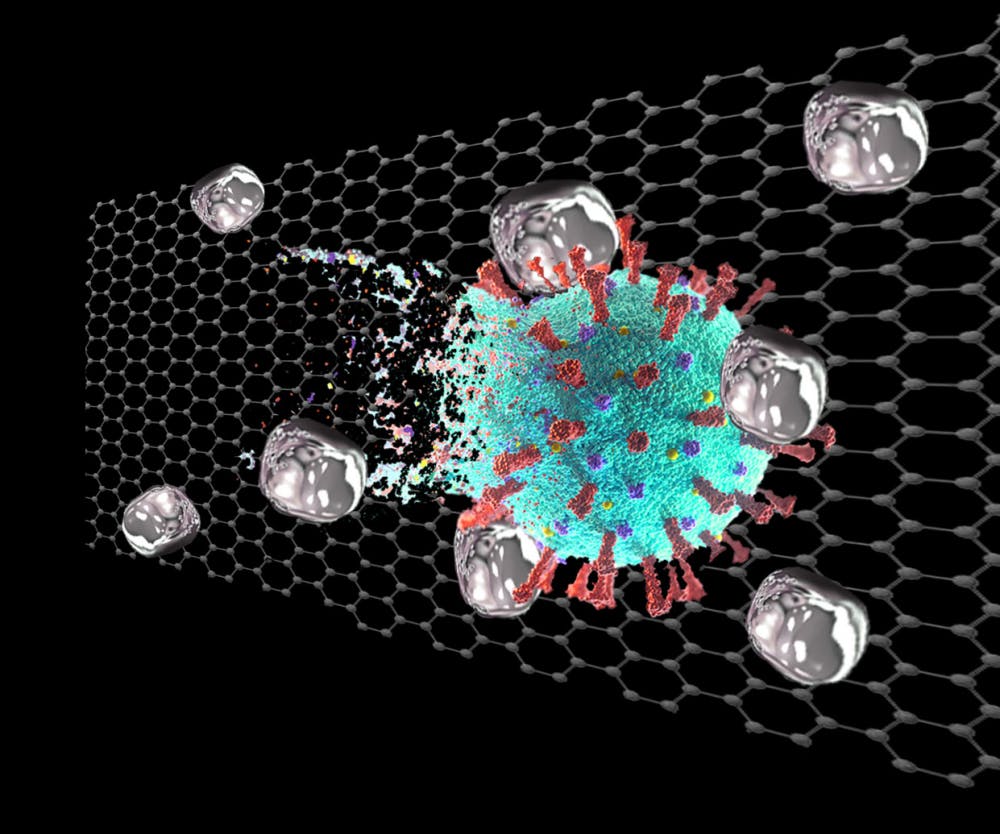

Graphene Composites, a company based out of the United Kingdom with a subsidiary at the CIC Providence in Rhode Island, specializes in the creation of nano-materials technology and has partnered with researchers at the University in its creation of graphene ink — an antiviral and antibacterial substance for coating PPE. If the substance is deemed effective and approved for use, equipment covered with it would be able to not only trap viral particles but also eradicate them upon contact.

Since GC’s inception, the company has sought uses for the world’s strongest material, graphene, and the world’s lightest, the shock-absorbent aerogel, said Sandy Chen ’88, the company’s CEO and founder. Their prior products have included “bulletproof shields for schools,” durable wind turbines and fabric coating that creates a scent-based invisibility cloak to protect against mosquitos.

The company began developing the active component of its COVID-19-fighting substance in March and worked on it into early June. They have since passed the product into the hands of researchers at Brown and the United Kingdom’s National Physical Laboratory for concurrent examination.

The active portion of this “ink” that could shield people from the coronavirus consists of many ultrathin sheets of graphene that are singly “studded with roughly 10,000 silver nanoparticles,” Chen said.

Scientists have known of silver’s germ-killing properties for years. But these silver molecules are much smaller than a SARS-CoV-2 invader. To ensnare the virus, flakes of the silver-coated graphene band together, allowing the silver to destroy the virus’ protective coating, jeopardizing the genetic material within so that the virus can no longer multiply. The graphene should thus stop the virus from passing through the PPE it coats.

GC’s collaborators investigating the product’s efficacy include Assistant Professor of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology Amanda Jamieson, the principal investigator on the University side of the project, Investigator Meredith Crane PhD’12 and Postdoctoral Associate Nivea Farias Luz. The decision to involve the University was “entirely logical” given that there’s a “real character at Brown that is about community involvement and doing things for the greater good and this (project), if anything, is exactly that,” Chen said.

Although lab regulations prohibit University researchers from studying the live SARS-CoV-2 virus, they have utilized the influenza virus to test how well their product can kill a virus, Jamieson said. The researchers hope these experiments will eventually be performed with the coronavirus and other infectious agents. GC hopes to roll out results in the coming months.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="650"]

GC is partnering with other manufacturers to obtain the PPE for coating. “We’ve done a good job building a coalition both locally, regionally and even nationally to distribute the products once the testing has been completed,” President of GC USA John “J.R.” Pagliarini said.

To ensure that the final coating is long-lasting, the researchers must also develop different base solutions — the liquid containing the tiny graphene-silver compound — for varying PPE materials, such as fabric, plexiglass or other materials being coated. Graphene alone in large quantities can be hazardous, but “what we’ve made sure of is that (the graphene is) not going to come off and cause harm,” Chen said. Eventually, the researchers hope their ink could be used on everyday materials, like sports equipment or phone cases.

“Coming in right in the middle of everything going on with this project, it was very clear to see that the motivation is not because it’s a very great financial opportunity but because it’s a very urgent need, and I think everybody in our team has been motivated to push that need and to find a solution,” Charlotta Gustavsson, the summer business intern at GC, said.

“These are unprecedented times as we all know,” Pagliarini said. “We are fortunate because we have the ability within this company to do something profound and transformative.”

A picture worth a thousand words

Adequate COVID-19 testing remains a major obstacle in curbing the virus’ spread. One COVID-19 testing method employs a laboratory technique, the polymerase chain reaction, to identify whether the SARS-CoV-2 virus’ genetic material, found in the form of RNA, is present in a person. This technique, while unaffordable in some countries and not always accurate, can be coupled with diagnostic and prognostic imaging like CT scanning, which has gained prominence in areas with limited access to other testing techniques.

Since February, University researchers have been working to “develop (artificial intelligence)-based diagnostic and prognostic software or tools that can be used to assist physicians (in) diagnosing COVID-19 accurately using imaging, as well as predict which patients are going to transition to severe diseases,” said Harrison Bai, assistant professor of diagnostic imaging, clinical educator and co-principal investigator of the project. This work involves adapting existing algorithms and creating new ones to recognize the characteristics of the new disease.

While radiologists are essential for interpreting the captured diagnostic images in a way technology cannot on its own, they are not immune to error — subtle yet crucial details can slip through on occasion, Bai said. This is where AI proves advantageous: AI can help spot the difference between COVID-19 and pneumonia, signs of which can appear identical on a lung scan during the initial analysis.

Additionally, this method of detecting the risk that COVID-19 poses to different patients could allow for more prompt and appropriate treatment plans. It could also help hospitals foresee the space and care they should expect to make available for these patients, thereby enabling a quicker recovery, Bai said.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="974"]

Principal Investigator of the project and Professor and Chair of Computer Science Ugur Cetintemel, co-principal investigator and Assistant Professor of Computer Science Ritambhara Singh and Associate Professor of Medicine Bharat Ramratnam ’86 MD’93 are also at the forefront of this research. The Seed Fund has further supported University students in computer science who have contributed to the work.

The researchers are in the process of monitoring and refining the technology in a simulated clinical setting without patient involvement. The team aims to have a final tool in use at Rhode Island Hospital and other clinical centers, where it could assist with the diagnosis and prognosis of COVID-19 and similar diseases like pneumonia.

“The most important thing is (the) clinical applications,” Bai said, adding that the final solution should cater towards the needs of the patients and health care providers who would be using and relying on these AI tools.