President Christina Paxson P’19 jolted awake one early morning in March with a grim realization. She would send an email to her students days later, instructing most of them to pack up their lives and leave College Hill.

“I'm usually somebody who has no trouble sleeping as long as I want to, and I woke up at four in the morning and it was just like, we have to move our students out,” Paxson said in a May 21 interview with The Herald, reflecting on the moment she knew that her leadership team would have to cancel on-campus learning and send most students home.

“This whole time period feels a little bit like driving through a thick fog."

The University’s senior team would meet in the morning of March 9, an unseasonably warm day in Providence, and officially decide to limit campus operations in response to the spread of the novel coronavirus. That meeting marked the end of weeks of back and forth as University leaders struggled to decide how to best proceed with the pandemic quickly unfolding around them. It also marked the beginning of a scramble to figure out how the University could help students and employees upend their lives while simultaneously developing an unprecedented online schooling operation.

“This whole time period feels a little bit like driving through a thick fog,” Paxson said. “You know that there are obstacles out there and you know that there are things you have to do, but (you are) trying to figure out how to do it.”

As many undergraduates quickly moved out of their dorms and prepared for a new style of learning, administrators were engaged in an intense decision-making process behind the scenes. University leaders interviewed by The Herald provided new details describing how they made the choices that ended on-campus learning, emphasizing the institution-wide collaboration that developed as they managed evolving circumstances.

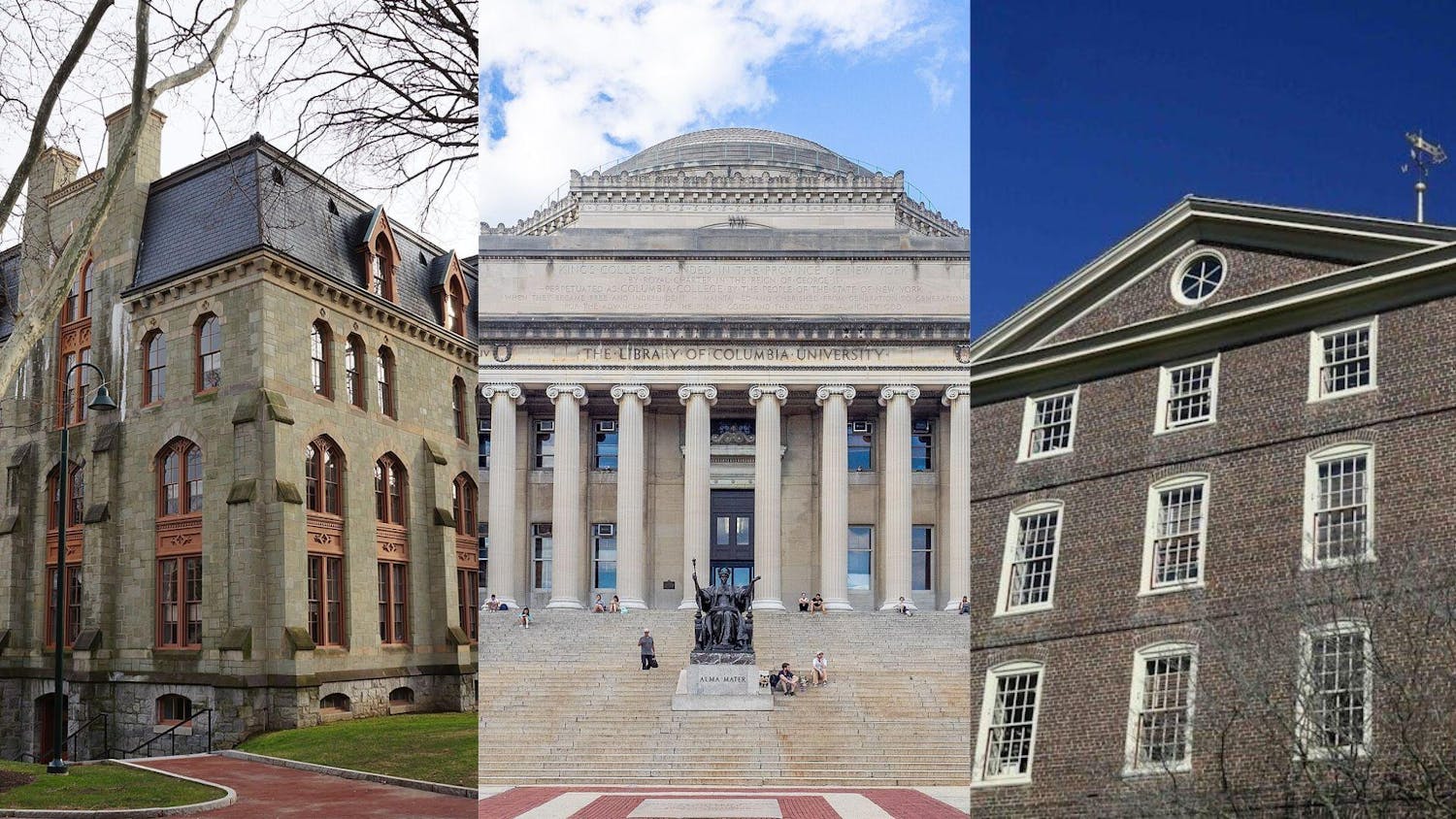

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="650" caption="Students sit on the steps outside of the Steven Robert '62 Campus Center on March 12, the day it was announced that classes would be canceled and classes would resume remotely. Two weeks later, campus had emptied."]

Preparing for ‘the unlikely event of a disruption to normal University operations’

Although the University’s crisis response efforts escalated in mid-March, the University’s Core Crisis Committee was thinking about the novel coronavirus by late January.

The Core Crisis Committee, which makes recommendations about decisions such as canceling large events, convenes to coordinate and oversee the University’s response to emergencies. It holds some regular meetings, but its members began to meet specifically about the coronavirus early in the semester, according to Russell Carey, executive vice president for planning and policy and the committee’s chair. Team members include representatives from the Division of Campus Life, the Department of Public Safety and the Office of the Provost, Carey said, though membership is meant to adjust based on what the situation demands. Ultimate decision-making power formally lies in the Policy Committee, which Paxson chairs.

Carey sent the first community-wide communication about the coronavirus Feb. 1, stating that the Core Crisis Committee was monitoring the situation. At that time, the committee did not anticipate that a near-complete shutdown of campus would occur by mid-March.

“I would say it was too early for what I would describe as long-term plans,” Carey said. “Particularly at that stage, it was not thinking about closing or having to go to remote operations or anything like that.”

In February, the Core Crisis Committee and other administrators began to address study abroad programs. They started to call for students’ return from hard-hit areas, formally canceling the Brown in Bologna program Feb. 28. The University employed existing policies to determine when programs should shut down based on factors including World Health Organization and State Department ratings.

As the coronavirus spread in Europe, administrators considered its potential to disrupt life on College Hill. By late February, the University’s Policy Committee began to meet more regularly to discuss the coronavirus, recalled Provost Richard Locke P’18.

“We were already telling faculty, look, you should be prepared, if we have to, to move your classes online or remote because we’re seeing what’s going on in Europe, we’re seeing what’s going on in other parts of the country,” Locke said.

At that point, the University had not yet halted non-essential domestic travel. Locke recalled “wiping down chairs and washing my hands repeatedly” in the Los Angeles International Airport in late winter, where he was traveling back from a trip for Brown.

The second campus-wide communication about the coronavirus would come on Feb. 29, encouraging heightened vigilance for students planning to leave campus for spring break or any other time in the coming months. The email explained that contingency planning was in place “to prepare for the unlikely event of a disruption to normal University operations.”

Behind closed doors on the final days on campus

In early March, campus leaders focused on instituting a response as the novel coronavirus spread through the United States. The University canceled in-person admitted students days and restricted events with 100 or more attendees. The Ivy League presidents canceled spring athletic practices and competition.

The University communicated regularly with the Rhode Island government, which had created its own committee to address the growing health crisis. University administrators continue to talk with state officials. For instance, Associate Vice President for Campus Life and Executive Director of Health and Wellness Vanessa Britto speaks with representatives from the Rhode Island Department of Health.

“Things were happening asynchronously.”

University leaders also communicated with members of other colleges and universities. The administration began to pay attention to the responses of the University of Washington and Stanford University early on, Carey said. As the pandemic progressed, the University communicated with other administrators in the Ivy League and Ivy Plus communities and shared information with colleagues at the Rhode Island School of Design and other colleges in the state.

“At every layer, people were talking to their counterparts just so we could be like-minded and learn from each other and at times collaborate, but we were on different academic calendars,” Britto said. “Things were happening asynchronously.”

In the afternoon of March 9, just hours after senior leaders at Brown made their decision, Gov. Gina Raimondo declared a state of emergency in Rhode Island. At that point, University leadership knew that on-campus learning would soon cease, but students waited anxiously for an update about whether they would finish the semester on College Hill..

“We were getting a lot of questions from students saying like, ‘we know you're going to make us leave, why don't you just tell us?’” Paxson said. “But we didn't want to make that announcement until we had all the support and resources in place for students.”

Before alerting students that campus would close, University leaders wanted to form a team that could quickly respond to students’ many questions concerning move-out, and make plans to offer financial support and other resources.

Paxson said that her senior team debated the question of announcing the decision earlier. “I think in the end we kind of hit it right,” she said.

From early in the crisis response, the Office of University Communications worked to provide information to the community while managing rapidly changing circumstances.

“Sometimes that's the most certainty that you can have in an uncertain situation,” said Vice President for Communications Cass Cliatt. “The certainty that you will be communicated with, the certainty that information will be provided to you, the certainty that there will be transparency around decisions that are being made.”

To make sure messaging remained consistent, accurate and in line with University values, a group led by Cliatt began to review and align all communications related to the coronavirus. “Any communication that was going to the campus had multiple eyes” from areas including communications, the Office of the Provost and the Office of the General Counsel, Cliatt said.

In addition to sending messages to students, the University also needed to communicate with employees. The University had maintained the employment of full-time and regular staff members as of earlier this month, and seasonal and intermittent workers were terminated in April, The Herald previously reported.

On the night before the student body was informed, William Zhou ’20 and Jason Carroll ’21, then president and vice president of the Undergraduate Council of Students, heard from Campus Life that Brown would be transitioning to remote learning.

“I think in the end we kind of hit it right."

“We provided feedback on after that decision was made, what was the best way to communicate it, what was the best way to support students through it,” Zhou said. “It was definitely a really hard and stressful time ... but I’m really thankful that overall (the administration) was doing what they could to keep us in the loop and getting our input.”

With the sudden move out, Paxson acknowledged that “from a student's perspective, there were probably times where it felt like they needed more support, certainly, but people were really just working 24/7.”

On the morning of March 12, students received the email first notifying them that dorms would soon close to most students. By March 17, almost everyone living on campus had moved elsewhere. Less than two weeks later, classes resumed online.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="650" caption="Students walk through Wayland Arch on March 12, carrying moving boxes. Weeks later, Wriston quad was quiet."]

What comes next?

On Saturday, March 14, two days after Paxson informed students that University residences would largely close, the University announced a positive coronavirus case in the community and worried that possible travel restrictions could inhibit students’ ability to leave campus. The deadline to move out changed from March 22 to March 17.

The previous day, Cliatt received flowers as a thank you for some of her work in the previous weeks, and she decided to leave them in the office for the weekend. The next day, the University would also announce that most staff would be required to work remotely.

“I haven't returned to my office since that Friday,” she said. “Those flowers I'm sure are still there, except wilted.”

The University has yet to announce whether students will return to campus next fall. In an April 26 op-ed in the New York Times, Paxson made the case for reopening college campuses in the fall under certain circumstances. The University is considering proposals for a full return to campus, a division of the year into three semesters or a fully remote fall semester, The Herald previously reported.

Some increased communication across peer institutions has also continued as Brown plans for the fall. Provosts within the Ivy Plus consortium usually convene twice a year for two-day meetings, but lately they’ve been talking on Zoom every week. Topics they discuss include reopening, testing and remote learning.

“Those flowers I'm sure are still there, except wilted.”

“We shouldn’t be competing on this. We should just be sharing best practices and knowledge,” Locke said. “Having that support group has been really wonderful.”

Locke lost his mother-in-law to the coronavirus in early April, soon after his own mother passed away. While practicing social distancing at the funeral, he was unable to hug his loved ones.

“It came to me personally how serious this was,” Locke said. “Protecting the health and safety of the members of our community had to be the number one goal.”

ADVERTISEMENT