University researchers recently discovered a new state of matter in which pairs of electrons called Cooper pairs conduct electricity as metals.

The new finding is built on a theory established by Thomas J. Watson, Sr. Professor of Science and Director of Brain and Neural Systems Leon Cooper in 1972, which describes how pairs of electrons can conduct electricity with zero resistance. His theory was so influential that Cooper and his colleagues won the Nobel Prize that year, and the pairs of electrons soon became known as “Cooper pairs.” But, in 2007, University researchers found that Cooper pairs could also act as insulators, meaning they do not conduct electricity at all. The recent study, conducted at the University by a team of researchers working with academics in China, shows that Cooper pairs can also conduct electricity at a constant rate like metals.

“There’s this very basic question: what is allowing this to be a metal?” said Professor of Physics Jim Valles, who co-authored the paper. “And if you can figure that out, then you begin to understand how you can manipulate it.”

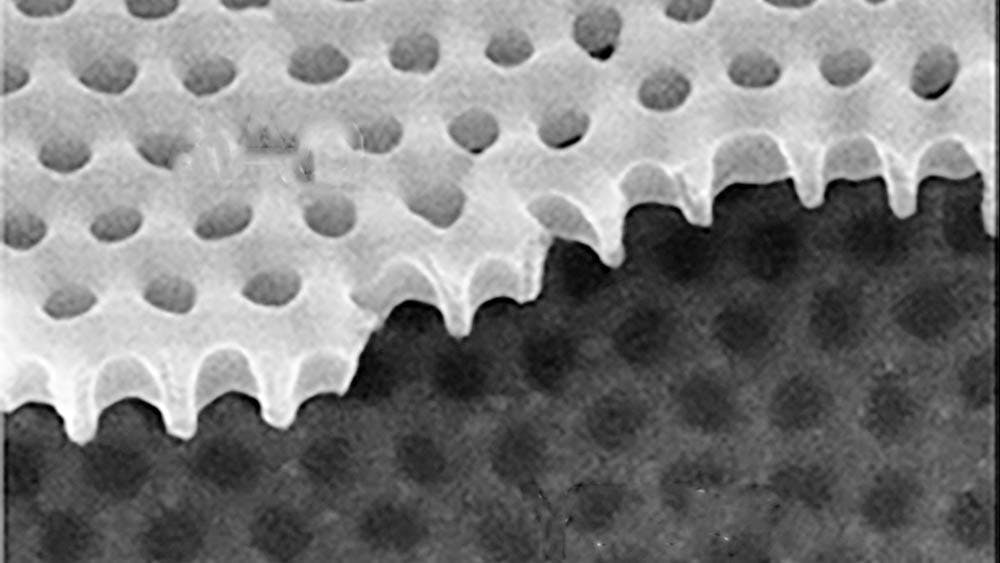

The researchers ran an electric current through a superconductor called yttrium barium copper oxide that had small holes in it. They then measured the frequency with which electrons circled these holes, and found that the electrons in this metallic state were moving in pairs. This state of matter, now known as Cooper pair metal, had yet to be discovered.

“It has the characteristics of metal, yet instead of individual electron movement in the metal, we now have pairs of electrons,” said co-author and Charles C. Tillinghast, Jr. University Professor of Engineering and Professor of Physics Jimmy Xu. “How it is different, we don’t know yet. It has metallic behaviors, but may also have something new and different yet to be discovered.”

Valles added that “getting Cooper pairs that will give you a resistance that is a constant value at low temperatures … is still mysterious. That’s that new state of matter.”

This discovery has opened doors to new avenues of exploration on Cooper pair activity. Researchers plan on studying this phenomenon further and using it to gain a greater understanding of what it means to be a metal. The hope among academics is that it could lead to new ways of understanding and manipulating electricity.

“It started as a curiosity driven question that grew into a large effort,” Xu said. “We have plenty of ideas on what to do next - interrogating this state, trying to make something useful, trying to manipulate it, trying to prove some more hypotheses and answer some more curiosity-driven questions.”