In stark contrast to the calls for fossil fuel divestment that are dominating college campuses nationwide, there is little unrest on Brown’s campus over the University’s holdings in fossil fuel companies.

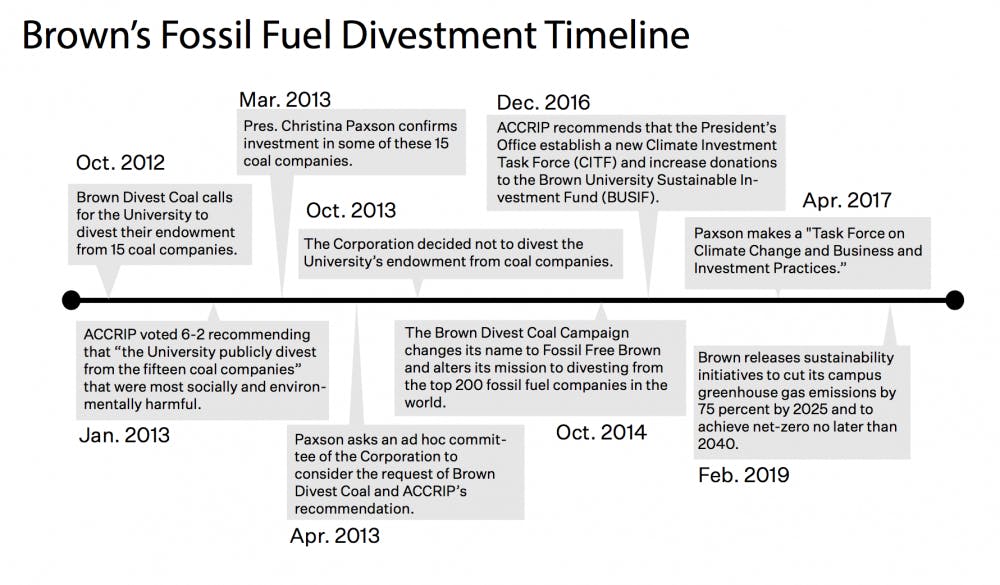

Brown has had a complicated history with fossil fuel divestment. Students spent three years advocating for divestment from coal then fossil fuels, but the administration dismissed these proposals in 2013. In a Dec. 2 interview with The Herald, President Christina Paxson P’19 reiterated her position that divestment from fossil fuel companies is ineffective for combating climate change. On the other hand, some students and faculty have begun to consider remounting a divestment campaign.

The Herald explored the way climate justice has manifested on Brown’s campus over the last decade, beginning with a campus-wide movement to divest the University from coal in 2012.

The first calls for fossil fuel divestment

When Brown Divest Coal Campaign began organizing at the University in 2012, the group gained traction quickly. They demanded that the University sever its financial ties with coal companies, who were at the time the “single largest source of global carbon dioxide emissions,” according to an op-ed penned by the group. Within the campaign’s first weeks, the group had garnered over 1,200 signatures of support on a petition and had over 60 volunteers.

“I don’t remember a single opposing voice from the student body,” said Nathan Bishop ’13, one of Divest Coal’s core organizers. “I think everyone saw it as a pretty clear-cut issue.”

“It was one of those cool moments at Brown where it was like, ‘Wow, these kids really want to get stuff done,’” said Dawn King, director of undergraduate studies for the Institute at Brown for Environment and Society, who supported the student organizers during the first push for divestment. “There were hundreds of students behind it. They were at the (Urban Environmental Laboratory) making posters every night, having meetings every night and they took it incredibly seriously.”

Divest Coal presented their argument to the Advisory Committee on Corporate Responsibility in Investment Policies in 2013, which went on to recommend divestiture. The committee wrote that the companies cited in Divest Coal’s proposal committed social harm “so grave that it would be deeply unethical” for the University to continue to profit from them.

Ultimately, the Corporation, the University’s highest governing body, and Paxson dismissed the proposal in 2013. Paxson wrote in an open letter at the time that divestiture would convey “only a nebulous statement — that coal is harmful — without speaking to the technological and policy actions needed to reduce the harm from coal.”

In the subsequent years, Divest Coal rebranded themselves as Fossil Free Brown to expand their goal for divestment from the top 200 fossil fuel companies in the world, The Herald previously reported. In 2016, ACCRIP recommended the University move toward sustainable investment using several tactics including a gradual divestment. The Committee focused more particularly, however, on the creation of a climate change task force and increased marketing of the Brown University Sustainable Investment Fund, as The Herald previously reported.

But the University has yet to publicly divest from any fossil fuel companies.

“(Divest Coal) made a really strong argument that coal was dying a natural death,” Bishop said. But the University “didn’t want to be bothered” with divesting and only wanted to focus on “what they thought was going to be the most lucrative investment,” he added.

Bishop characterized the end of the divestment campaign as “depressing.”

“It’s absolutely a national phenomenon with these massive prestigious schools divesting, and the fact that the institution has crushed a student movement when it’s been so strong, is going to be a real stain on the institution’s reputation,” he added.

Status of Divest at Brown

While activists at other Ivy League universities prioritize divestment as a key part of their climate justice movements, environmental student groups at Brown have focused heavily on pressuring state and local legislators to support policies, such as the Green New Deal. Currently, no fossil fuel divestment campaign is underway on campus.

Sunrise Movement Brown and Rhode Island School of Design, one of the University’s most prominent environmental justice groups, has instead focused their efforts on pushing for a state-wide Green New Deal and organizing climate strikes in Providence.

“For the foreseeable future, we don’t see ourselves doing divestment I think because there are already other campaigns fighting for divestment,” said Yesenia Puebla ’21, a co-hub organizer of the group, in a Nov. 24 interview with The Herald. She cited the reluctance of Sunrise members to take attention away from the current push for the University to divest from companies facilitating human rights abuses in Palestine. She also said that members of Sunrise aren’t particularly excited about pushing for divestment.

“If we’ve already failed, I wonder how much of our efforts are worth it,” she said. “We see that mobilizing … will be more effective for a statewide Green New Deal which is eventually what we want, so we really don’t see ourselves doing divestment.”

With Sunrise more focused on statewide issues, a new group, Climate Action Now, formed in October with an intention to achieve climate justice at the University level. Galen Hall ’20, a columnist for The Herald, and Andrew Javens ’21, two leaders of the group, hope to “form a vision for how Brown could be transformed in light of the climate crisis.”

Among the multiple ideas they are considering, they hope to advocate for an interdisciplinary curriculum at the University that addresses the urgency of climate change.

Javens and Hall said they did not believe that divestment was the only answer in helping the University improve its environmental policies, but it could be “one option among many,” Javens said. Fossil fuel divestment contributes to “stigmatizing and politicizing the issue of fossil fuels, pushing people to take sides on the issue,” he added.

“We don’t want to take divestment off the table, we just want to think more broadly as well, and figure out when it would be more opportune to push for something like that,” Hall said.

Professor of Environmental Studies J. Timmons Roberts reiterated this point. “On divestment, it’s often argued that other investors will just buy up shares if we sell them in these companies,” he wrote in an email to The Herald. “This is about something else: taking away the social license of these firms that are undermining our science, and our futures.”

But in an interview with The Herald, Paxson said that if a divestment campaign were to begin again, she would stand by her decision from 2013.

“Right or wrong, (divestment) is just not effective,” she said. “I don’t see how it does any good. In some ways, if people think that that’s all they need to do, and that it lets them off the hook … that’s a really easy way out of doing the hard work of actually making real change.”

Referencing the University of California system’s decision to divest its endowment and pension fund from fossil fuel companies, Paxson said, “They didn’t really divest. I think they said they wouldn’t be buying any more for now because they didn’t think it was a good investment.”

“Four years ago, when people wanted Brown to divest from coal … we had less than a million dollars in coal because it wasn’t a very good investment. Natural gas had really come and pushed coal out of the market. We currently make decisions about any type of investment in terms of what its potential future return is.”

Paxson also emphasized that she chose not to release the amount the U. invested in coal in 2013 because she preferred to keep the focus "on principles rather than dollar amounts."

Paxson added that the University’s current investments in coal are quite insignificant, but she declined to share the University’s current level of investments in fossil fuels.

Actions the University is taking

Rather than divesting from fossil fuel companies, the University has focused on reducing campus greenhouse gas emissions. In February 2019, the University announced its goal of achieving net-zero emissions by 2040.

To achieve its goal, the University created the Longer-Term Sustainability Study Committee, co-chaired by Assistant Provost for Sustainability and Professor of Environment and Society and Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Stephen Porder. The committee crafted a plan that includes two clean energy projects, converting the University’s central heating plant to run on bio-oil and renovating buildings to increase thermal efficiency.

Porder said that the University’s plan for net-zero emissions is “financially, logistically and technologically feasible” and would place Brown in the top tier of universities in terms of climate action. He added that the net-zero initiative is more effective than divestment for improving the University’s sustainability. Divesting from fossil fuel companies, he said, “won’t keep a single molecule of carbon out of the atmosphere.”

“Skepticism about divestment has nothing to do with a desire for inaction on climate change,” he said. “I am laser-focused on the rapidity with which the earth system is changing and the incredibly pressing need to reduce emissions as fast as possible, and divestment to me is a very ineffective tool to do that.”

Javens and Hall said that while the net-zero plan is a good start, they feel the University should do more to take a political stand on climate change. The two hope that the University expands its climate plan to include political advocacy for climate legislation on a state and national level.

“Taking the moral lead as an institution means both reducing our own footprint which we have a good plan to do, and then leading in our political-social business engagements in Rhode Island and nationally,” Hall said. “Are we addressing climate injustices? Are we pushing for climate action?”

Divestment on other campuses

This November, over 200 students and alums from Harvard and Yale interrupted a football game with a demonstration calling for both universities to divest their holdings in fossil fuel companies. The action made headlines across the country, placing the fossil fuel divestment movement in the national spotlight.

Harvard and Yale are far from the only two Ivy League universities with increasingly active fossil fuel divestment campaigns. At Penn, Fossil Free Penn members stage a weekly four-hour sit-in inside the university’s College Hall, where President Amy Gutmann’s office is located. At Dartmouth, Divest Dartmouth unfurled a large banner reading “Divest” in front of the school’s main library to call for divestment from certain oil and gas companies last spring. And over the summer, the University of California system announced that its “endowment and pension-fund were going ‘fossil free.’”

“(Divestment) is a necessary step to take to reduce carbon emissions,” said Maeve Masterson, an organizer for Fossil Free Penn.

After a previous divestment movement failed in 2015, Fossil Free Penn renewed their efforts in 2018 when they presented an argument to their Board of Trustees to divest. The group moved to more action-oriented tactics after the Board denied their proposal.

“The point of our non-violent direct action strategy is really to place a lot of pressure and reputational damage on the Board of Trustees, knowing that they are the ones that are capable of making this decision,” Masterson said. “We call it a campaign of continuous embarrassment — we’re trying to make it as disruptive as possible, and make it so that their business as usual is no longer able to happen comfortably.”

Masterson said that raising awareness of this “silent crisis on campus” to the student body can help place “pressure on our administration to take action.”

Divest Dartmouth has maintained a campaign for seven years, which has seen its goals evolve over time. Students are currently advocating for the college to disclose its “limited investments” in fossil fuel companies. In addition, the group changed their tactics after the administration refused their proposal for divestment from the 200 most-polluting fossil fuel companies, said Edel Galgon, a member of the group. Now they are asking for divestment based off the “companies with the worst corporate practices and the most misinformation about climate science,” Galgon added. To compromise with Dartmouth’s administration, the group judges companies based off the Union of Concerned Scientists’ climate accountability scorecard.

Roberts praised the protest at the Harvard-Yale game, saying that “University students have been the leaders of many protest movements, through history and around the world.” He added that “the moment is back, and it will keep coming back until we divest.”

Correction: Due to an editing error, a previous version of this article stated that President Paxson reiterated her support for the University's investments in fossil fuels. In fact, President Paxson reiterated her position that divestment from fossil fuel companies is ineffective for combating climate change. The Herald regrets the error.

Clarification: A previous version of this article did not explicitly state that President Paxson described the choice not to divest from coal in 2013 as driven by principles rather than financial considerations. The article now includes the following context: Paxson also emphasized that she chose not to release the amount the U. invested in coal in 2013 because she preferred to keep the focus "on principles rather than dollar amounts."