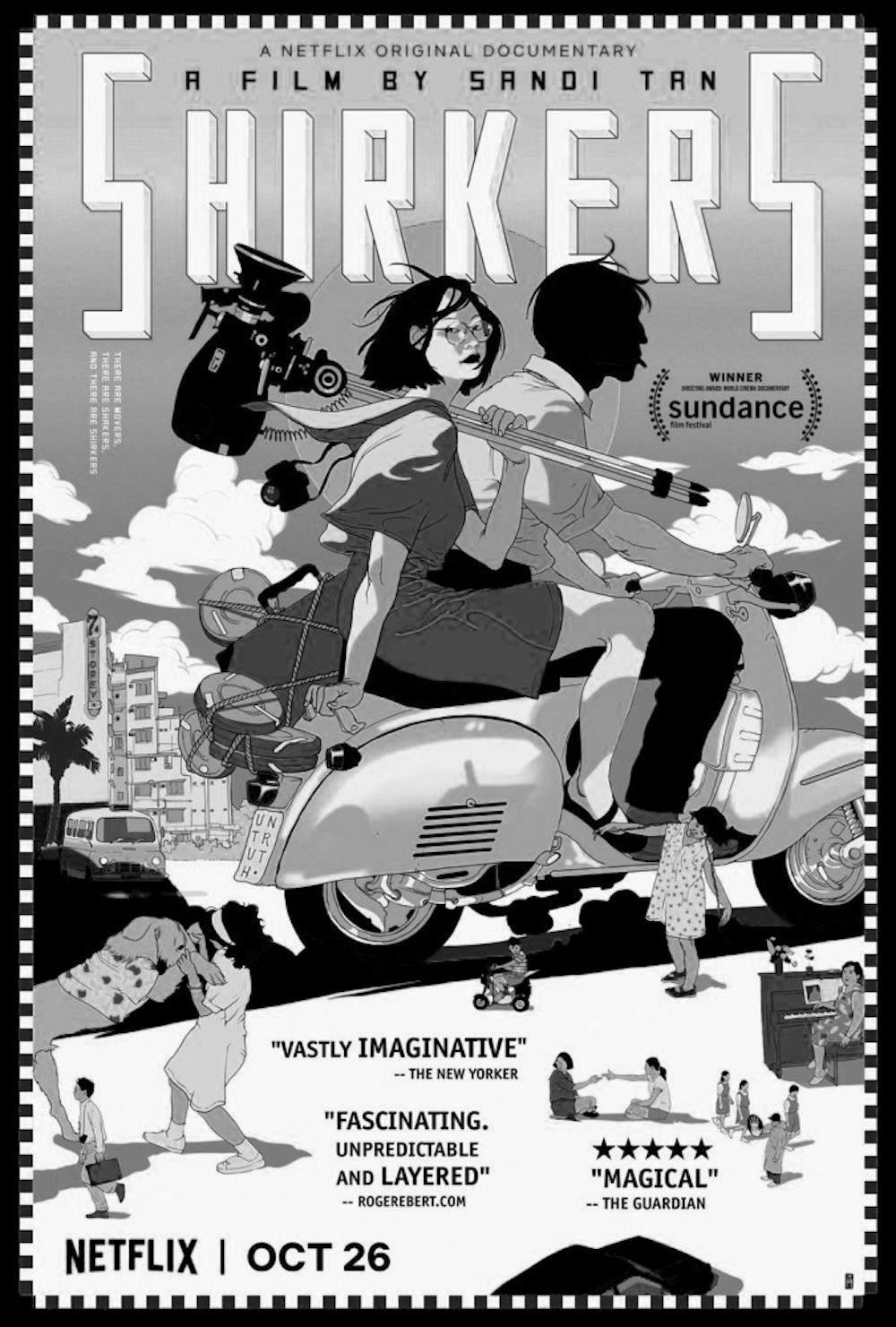

During the summer of 1992, Sandi Tan partnered with her friends Jasmine Ng and Sophia Siddique and her mentor Georges Cardona to shoot an independent road movie called “Shirkers” on the streets of Singapore. After returning to college, Tan discovered that Cardona had stolen all the footage, leaving her and her friends traumatized.

Twenty-three years later, Tan used the eventually recovered footage to develop her documentary film of the same name. The documentary focuses on the events surrounding Tan’s youth, the production of the original feature film “Shirkers,” the mysterious legacy of Georges Cardona and much more. It marks Tan’s road to recovery after decades of carrying the weight of the loss of the original footage.

Tan knew that her story would make for a more interesting film than just the original concept.

“It’s like an editorial feat to have combined all those years of footage,” said Alexandra Anthony, a senior critic at the Film/Animation/Video department at Rhode Island School of Design. The film exists as a “mosaic,” poetically showcasing Tan’s “interpersonal relationships with other collaborators (and) history of her own passion for film,” Anthony added. The film cut together footage from the original “Shirkers” movie, with other pieces of evidence documenting Tan’s experiences with Cardona and new footage of her interactions with Ng, Siddique and Cardona’s widow, who remains anonymous in the film.

Tan visited RISD on Monday to speak about “Shirkers” — which won the World Cinema Documentary Directing Award at the Sundance Film Festival in 2018.

“The reason I made (the original) film is because I grew up in a place which I saw was disappearing before my very eyes in 1992, and this film was an excuse to put everything I cared about and everyone I cared about and everyone I thought was kind of funny-looking and goofy-looking, and I captured them on film before they all vanished.”

Losing the original footage was “such a painful experience and also so shameful,” which became an unspoken secret among her and her friends, even though none of them could have foreseen that Cardona would have stolen the footage. She eventually moved on with her life, pretending it had never happened — until Sept. 11, 2011. That day, she received an email from Cardona’s widow, who had discovered the footage and offered to return it. Opening up that discussion was like “reviving this ghost or reanimating a corpse that you don’t want in your life anymore,” she said. Cardona had not only stored 70 cannisters of 16mm film, but also storyboards, log sheets, faxes to bus companies and even receipts to parking tickets, much to her surprise.

“When you put seven boxes stacked on top of each other, they’re vertical, they resemble a vertical coffin, like a sarcophagus or something. This thing began haunting my life for three years before I had the courage to open them up,” Tan said.

She feared that the footage would be “rotten” and “all the stories that I had played in my head were for nothing.”

In the end, she wanted the film to be a portrait of Georges and of friends. “He wants to be remembered; he wants to be mythic. I was very resistant to making this film because I didn’t want to make Georges mythic, I didn’t want to have him be remembered … I was fighting against that, but you can’t tell this story without telling Georges’s story.”

But despite their history,“to this day, he’s the best storyteller I’ve ever met,” she said.

“People were afraid for me,” Tan added. But she knew she had to follow the project through to completion — “This is a story only I can tell.”

Making the movie out of the 16mm film would also be extremely expensive. She eventually worked with colorists who had worked on Kirk Douglas movies, aspiring toward a ’50s and ’60s film palette, inspired by “what Wes Anderson might have been going for in his films.” After reviewing the film with a colorist, Tan realized the footage might have appeal for a “wider audience.”

She also felt responsible for “all these people who just gave it their best shot and had their futures kind of stolen away from them.” Tan and her friends had employed a dedicated cast of actors who had volunteered their time, on top of full-time jobs, to be in an independent film shot by college students.

“One of the joys of creating a film like this … is you get to create your soundscape.” Tan wanted the audience to be moved back and forth in time: “To do that, you have to capture the people emotionally.” She believed that collaborating with a sound designer was “working with an artist that you can really play with.” She also worked with an editor who had never worked on a full-length feature film and was therefore willing to experiment.

“The fact that she is so open to using people with less experience in the film industry, giving them both practice and exposure, is extremely inspiring to me,” said Tamia Jackson, a sophomore at RISD.

“Back in 1992, if we finished it and we showed it, they would have laughed us out of town. … We would have just felt like failures and never pursued it. Whereas the fact that it was never finished kept the dream alive for all of us.”