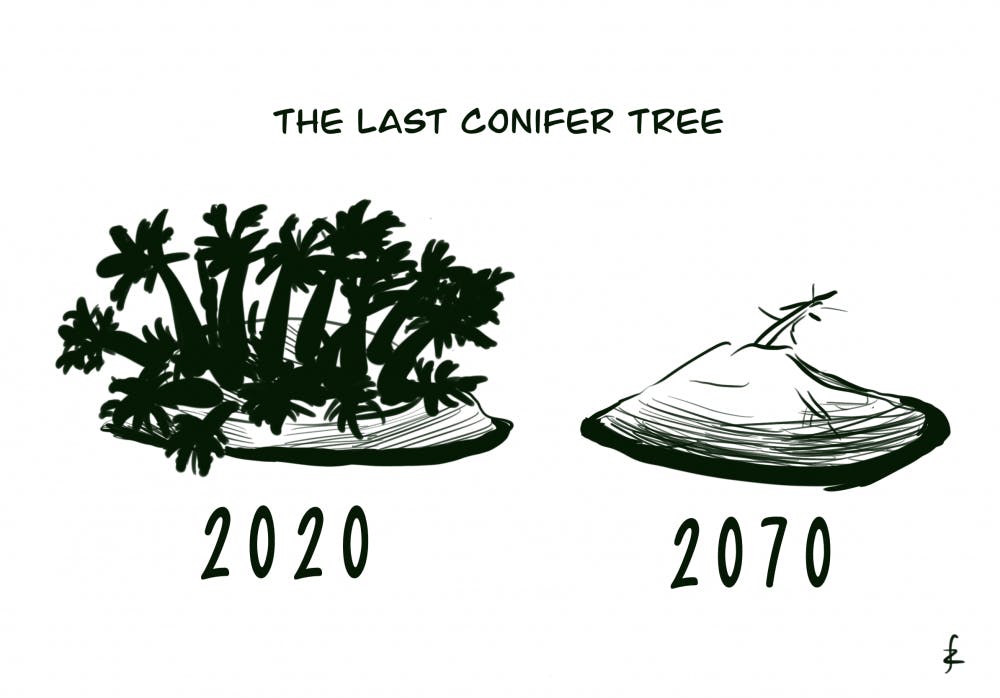

Some trees like the Norfolk pine and other island-native conifers may become extinct by 2070 due to the effects of climate change, according to University research published this summer.

Up to 25 percent of all conifers — a group of trees that includes firs, redwoods and pines — could become extinct on some specific islands.

The paper, published in Nature Climate Change, combined climate data from the conifers’ native islands with data from other places where the conifers were known to survive to estimate the broader range of climatic conditions the species can handle, said Kyle Rosenblad ’10, lead author of the study.

“We wanted to know two things,” said Donny Perret GS, a graduate student studying ecology and evolutionary biology and another of the paper’s authors. “One, how big is the ‘climatic buffer,’ or, rather, how many different sets of conditions can (these trees) cope with?” The study showed that, although conifers may naturally inhabit a very narrow climate, they are actually able to survive or sustain populations in much broader climatic ranges, he added.

The study found a relationship between the size of a species’ fundamental niche — the conditions under which a species may be able to survive — and the size of a species’ realized niche — the conditions that the species actually experiences currently — said Dov Sax, deputy director of IBES and professor of ecology and evolutionary biology.

“We showed that there does appear to be a really strong positive correlation between the two … and there is much more work to be done on the idea,” Rosenblad explained.

“The next question that follows is, will that help them in future climates?”

With these goals in mind, the study examined conifers native to specific small islands, as they are well-studied, of particular conservation interest and are commonly planted in diverse climates, Sax said. “We built models of what conditions these species … demonstrated an ability to tolerate, and (we) compared that against what conditions they are expected to experience in the future under a few different climate change scenarios,” Rosenblad said. “By and large, almost every single one of our study species was surviving and maintaining populations or at least just surviving, if not reproducing, in a much, much broader range of climate conditions than just what is found on the native island.”

Even though trees can survive under varying conditions, they will likely not be able to sustain the climate predictions for the year 2070, Rosenblad said.

The study also concluded that species native to smaller islands are at greater risk of extinction, Sax said.

“The smaller the island, the worse the outlook for these species,” Perret said.

Although the conifers have previously survived natural climate fluctuations, “the changes that we are expecting in the next 100 years or so will have consequences far more severe than they have been in past climatic shifts” with regard to the small-island species in the study, Perret said. “It drives home the point that this is unprecedented in the evolutionary lifespan of these species.”

“That’s the bad news,” Sax said. “The good news is that not all species are doomed. A lot of them are not and, among the ones in trouble, they vary. There are a range of approaches we can take. It’s not the end of the world for island conifers.”

While many of the species examined in the study may one day become extinct, there are certain actions that could preserve some of the at-risk species, Sax said.

“There’s this window for potential conservation management, where if a species is surviving okay, but the climate is making it too hard to reproduce and recruit new generations, there could be a role for some really targeted management interventions to help grow seedlings, make sure they reach maturity and plant them,” Rosenblad said. Nurturing seedlings could be one way to help conifer species reproduce in conditions where they otherwise may be unable. “It would be a different way of looking at what constitutes a ‘natural forest,’ but it is better than the alternative, which is losing the forest,” he said.

Moving forward, this study allows researchers and environmental scientists to better understand the risks facing these conifers and engineer targeted strategies to protect them and other island-native species, Rosenblad said.

“There is this sense that a species evolved in a place and it has a sort of increased value in that place,” Sax said. “We are tweaking the world in some profound ways. It would be nice to be able to preserve species within their native distribution whenever possible.”