Landlords will be banned from discriminating against potential low-income tenants who intend to pay rent using federally-funded housing vouchers, if an ordinance introduced to the Providence City Council March 21 passes.

Mayor Jorge Elorza and a majority of City Council members support the proposal, according to a city press release.

Although the Federal Fair Housing Act currently prohibits housing discrimination based on a myriad of factors such as race, gender and religion, Rhode Island landlords can still reject prospective tenants due to their source of income, according to the press release. The ordinance would prevent discrimination based on “lawful alternative source of income,” such as Section 8 housing vouchers, Social Security or child support.

This type of housing discrimination is a serious obstacle to those looking to obtain affordable housing, wrote Victor Morente, spokesperson for Elorza, in an email to The Herald. Many landlords adopt a “blanket policy” that denies families who participate in the housing voucher program an opportunity to rent, he added.

President of Providence Apartment Association Clinton Aneni said landlords are in support of eliminating housing discrimination, but he questioned some of the specific language used in the ordinance. “You can’t ... find out how (a potential tenant) generates their legal source of income,” he said. He added that he personally has not witnessed fellow landlords discriminating based on source of income.

The Providence Human Relations Commission will enforce the ordinance by taking housing complaints based on income discrimination. Currently, they are not able to do so. “We would expect source of income discrimination complaints to make up the majority of housing complaints if enabling legislation were to pass,” Morente wrote.

Only 34 percent of listings in Rhode Island are affordable for those using housing vouchers, said Lucas Fried ’21, who worked on the SouthCoast Fair Housing report cited in the city press release. When housing discrimination is taken into account, the number drops to 7 percent, he said.

Getting a housing voucher can take five to seven years and once received, holders are given 60 to 90 days to find housing, or they are forced to turn it in, according to Nathaniel Pettit ’20, who also worked on the report. Though the voucher is widely seen as the solution for those struggling to find housing, “there is usually yet another massive hurdle, which is finding a landlord who will accept it,” he said.

In Rhode Island, many voucher holders are families, single women and people of color, according to Pettit. “Allowing something like source of income discrimination certainly allows more orthodox forms of discrimination to continue,” he said.

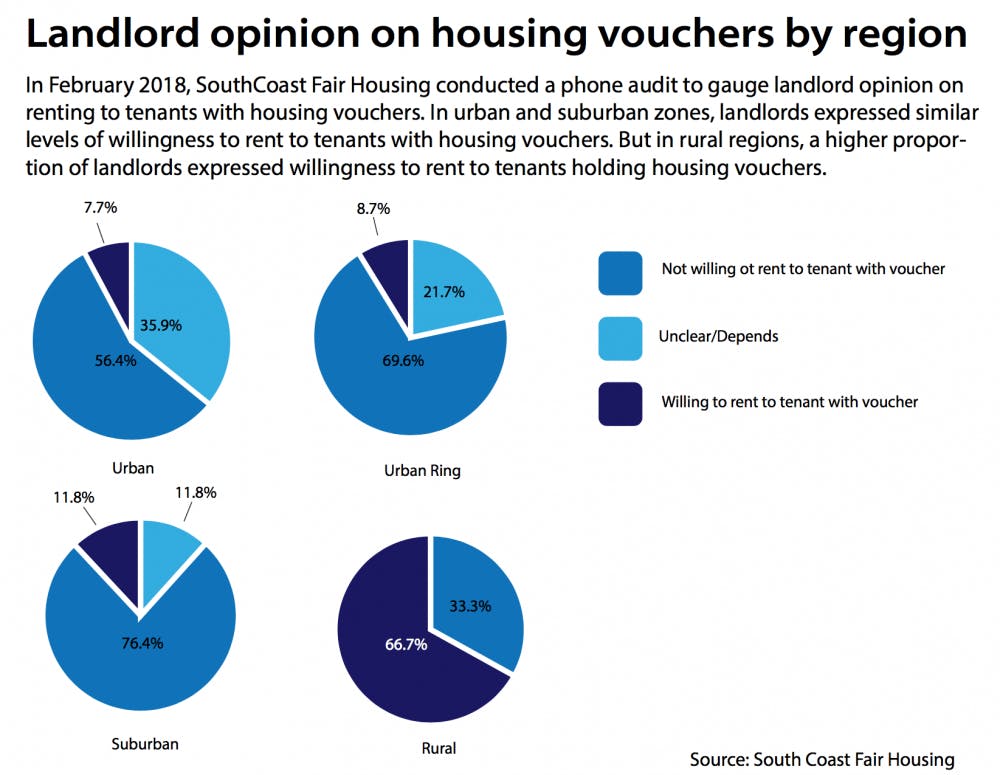

Although both Fried and Pettit stressed the importance of the city ordinance, Fried also added that “a lot of the refusals we saw were outside of Providence,” and that passing state legislation is the ultimate goal. The ordinance mirrors statewide legislation that passed in the Senate last year but did not pass in the House, according to WPRI. Similar legislation was introduced earlier this year, The Herald previously reported.

Pettit echoed this sentiment, adding that statewide geographic mobility was a cornerstone of the voucher program in order for families to take advantage of better schools or employment options in different areas. “The program was intended in large part to let people move to areas of opportunity,” he said. “By not addressing discrimination in more suburban, more white communities, we are undermining the original intent of the program.”