After watching the 2016 film “Hidden Figures,” which detailed the lives and work of three black women at NASA in the 1960s, many viewers were left inspired as the film shed greater light on the concealed contributions of women in STEM. But for Assistant Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Emilia Huerta-Sanchez and Rori Rohlfs, assistant professor of biology at San Francisco State University, the film sparked a research project.

Huerta-Sanchez and Rohlfs didn’t have prior knowledge of the women featured in the film, despite working in the same fields as them. This pushed them to consider how many other women they didn’t know of who had made significant contributions to those fields, Huerta-Sanchez said.

Huerta-Sanchez and Rohlfs worked to find female scientists in history who were denied authorship on research publications but deserved and would have earned that level of recognition by today’s standards.

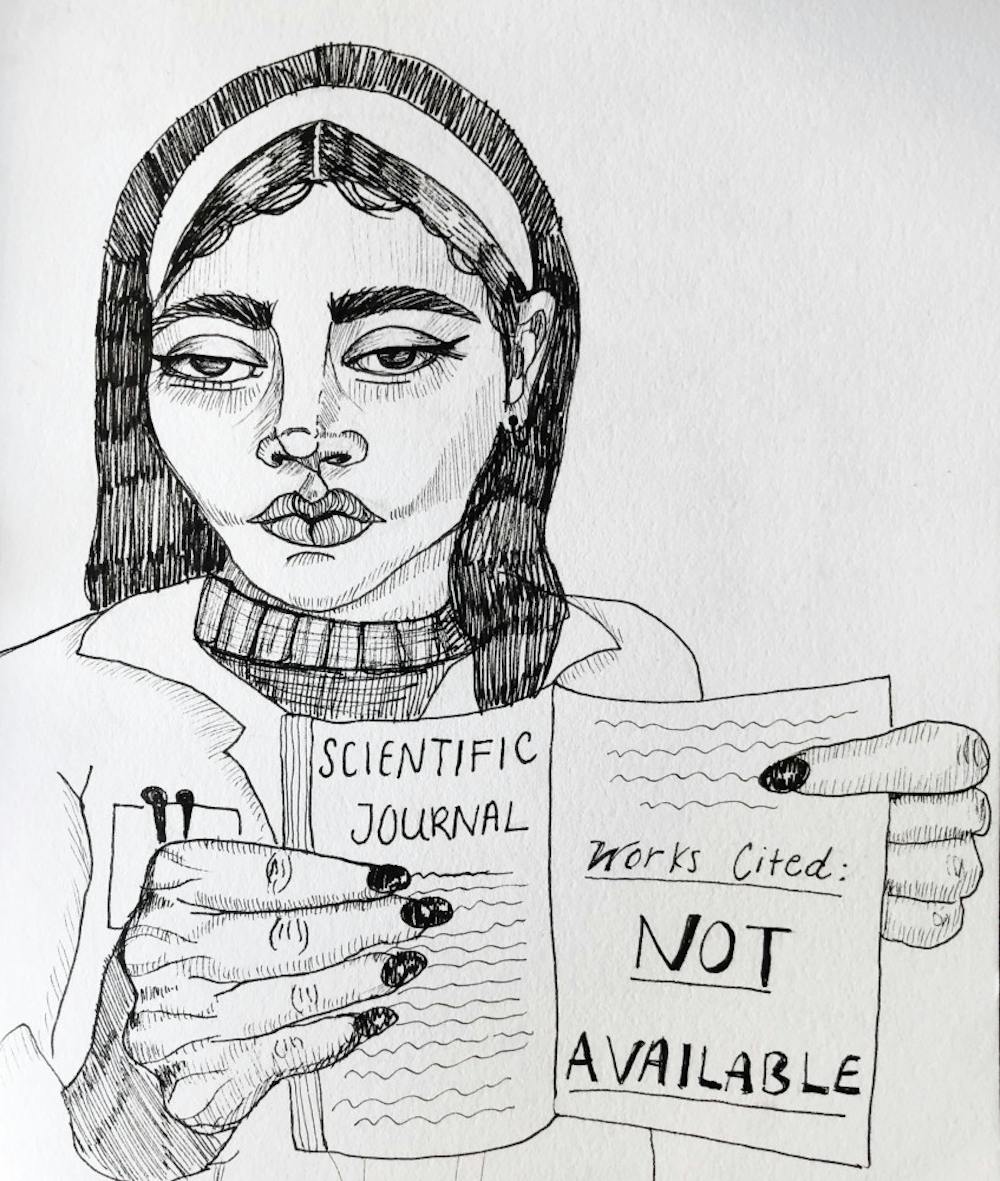

Before seeing the film, a paper caught Huerta-Sanchez’s eye because it barely acknowledged high school graduate Jennifer Smith for her graduate-level computation and programming work — tasks similar to the ones that earned Huerta-Sanchez authorship in publications. She had dismissed the example as just another historic case of unfair and unequal treatment of women. But the difference in attribution was significant because authorship in research is equivalent to “academic currency,” Huerta-Sanchez said.

Given their work in population genetics, Huerta-Sanchez and Rohlfs decided to peruse two-decades-worth of pages in the Theoretical Population Biology journal to find uncredited female scientists. The team picked the Theoretical Population Biology journal since it included studies that involved both theoretical and computational work, Huerta-Sanchez said. They looked at editions of the journal dating from its inception in 1970 to 1990, she added. “You just keep seeing things, and no one does anything about it,” she said. Samantha Dung, who worked on the project and is a recent graduate of San Francisco State University, said she was intrigued by the project and the opportunity to highlight the work of women in these fields.

The researchers then tried to obtain information about the authors and anyone given acknowledgements in the published research papers. They sometimes struggled to determine whether the contributors were men or women, since some citations included only initials.

Discovering more women who were involved in research through this study was “sad and validating at the same time,” Huerta-Sanchez said. “The field actually had more women than we thought,” she said, but it’s “depressing that … not knowing about them has created a false narrative that women don’t like STEM.” She was also “surprised that … there were a lot of women that were acknowledged, and there were some recurrent women as well” whose names could be found in other journals although none were given authorship. While she said that it is difficult to determine the extent to which these acknowledged women contributed, the work they performed often involved algorithms and complex thought, and repeated references suggested that they were skilled within their fields.

Dung was also surprised by the large amount of data that showed how “a lot of females, especially during the 1970s, actually did a lot of the … programming” but still were not given authorship.

Discussions with some of these women supported the significance of their contributions, Huerta-Sanchez said. The team spoke with Margaret Wu, who Huerta-Sanchez said was difficult to find and get in contact with because she was identified as M. Wu in the papers. After reaching out to authors on her studies, they found Wu in Australia.

When the researchers interviewed her, Wu did not seem upset about the lack of credit she had received, Huerta-Sanchez said. But learning the context of Wu’s work “gave (Huerta-Sanchez) the confidence to feel that those were significant contributions,” that warranted authorship. In her work, Wu executed tasks independently, though she was given instructions from her boss. Wu doesn’t necessarily represent all women in science of her time — she may have been more independent than others, Huerta-Sanchez added.

Huerta-Sanchez hopes that “we can begin to change the narrative that … there’s been a lack of women in science or that women don’t like science,” she said. Other goals include increasing awareness in young girls about women in STEM and challenging the historical disparity that resulted from “authorship norms of the time (that) hid their contributions.” She also believes the results are applicable to other fields. The team intends to identify women in biology next and is seeking funding so they can unveil the roles of more unidentified women.

Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology at Indiana University Eva Pietri was not involved in the study but has focused on stopping gender bias and increasing diversity within STEM-related disciplines. She said that “gender bias doesn’t always have to be this conscious, deliberate action meant to hurt women; it sometimes happens in very subtle forms.” Accordingly, the study “did a really nice job raising awareness of an issue that women were not getting those authorships, that they were just getting acknowledged,” she added.

Pietri hopes that highlighting these female researchers who were not adequately cited in the past will further other women’s interest in the field today and prevent history from repeating itself. “There’s this stereotype generally of certain STEM fields being … the person working alone,” Pietri said. “This paper does a really nice job dispelling that stereotype” because it shows that, even though the authors may have been men, they often worked alongside groups of women, she added.