“Until, Until, Until…” a performance directed, written and produced by Los Angeles-based artist Edgar Arceneaux was staged in Studio 1 at the Granoff Center for the Creative Arts on Thursday, Friday and Saturday nights last week. Presented by the Brown Arts Initiative, the multimedia play reimagines and re-enacts Broadway actor Ben Vereen’s 1981 performance at former president Ronald Reagan’s inaugural ball.

The event’s program explained that in the original performance, Vereen gave an homage to vaudevillian Bert Williams, one of America’s first mainstream black entertainers, by performing the 1912 hit song, “Waiting for Robert E. Lee,” in blackface as Williams had been required to do during his vaudeville productions. Vereen followed his first song with a performance of Williams’ song “Nobody,” which commented on the harmful history of racial stereotypes within performance as he emotionally wiped the makeup off of his face.

But in its televised program of the event, ABC chose not to air the last five minutes of Vereen’s performance — losing the political statement he had intended to make. Controversy ensued, as viewers had only seen Vereen, a black man, dance and sing in blackface in front of Reagan.

Traveling through time and space, Arceneaux’s piece invited audience members to consider not only this original commentary but also the effects of ABC’s omission on Vereen’s reputation.

The play began with a quote from Vereen, printed in large typeface on a semi-transparent curtain pulled across the stage. In part, it read: “I thought that it went well. Everyone was congratulating me when I left the stage. Two days later my conductor said to me, ‘brace yourself.’” The curtain opens to reveal actor Frank Lawson, playing Vereen, rehearsing his entrance to Reagan’s inaugural ball.

The hour-long performance continued with a series of other scenes, including one featuring actress Jes Dugger, who played Marie Osmond, the singer at the inaugural ball who followed Vereen’s act. Near the show’s conclusion, stage assistants stepped into the audience, beckoning them to enter the curtained, square stage area. Most of the audience followed the assistants into empty chairs along either side of the stage. Lawson applied the black-and-white makeup to himself and resumed the performance. After an imaginary bartender rejected his request to serve the audience drinks, Lawson’s subsequent dialogue conveyed his frustration at being denied service due to the color of his skin.

Lawson’s character then proceeded to sing Williams’ seminal song “Nobody.” During this performance, Lawson removed the black makeup from his face, signaling the portion of Vereen’s original performance that ABC denied viewers across the nation.

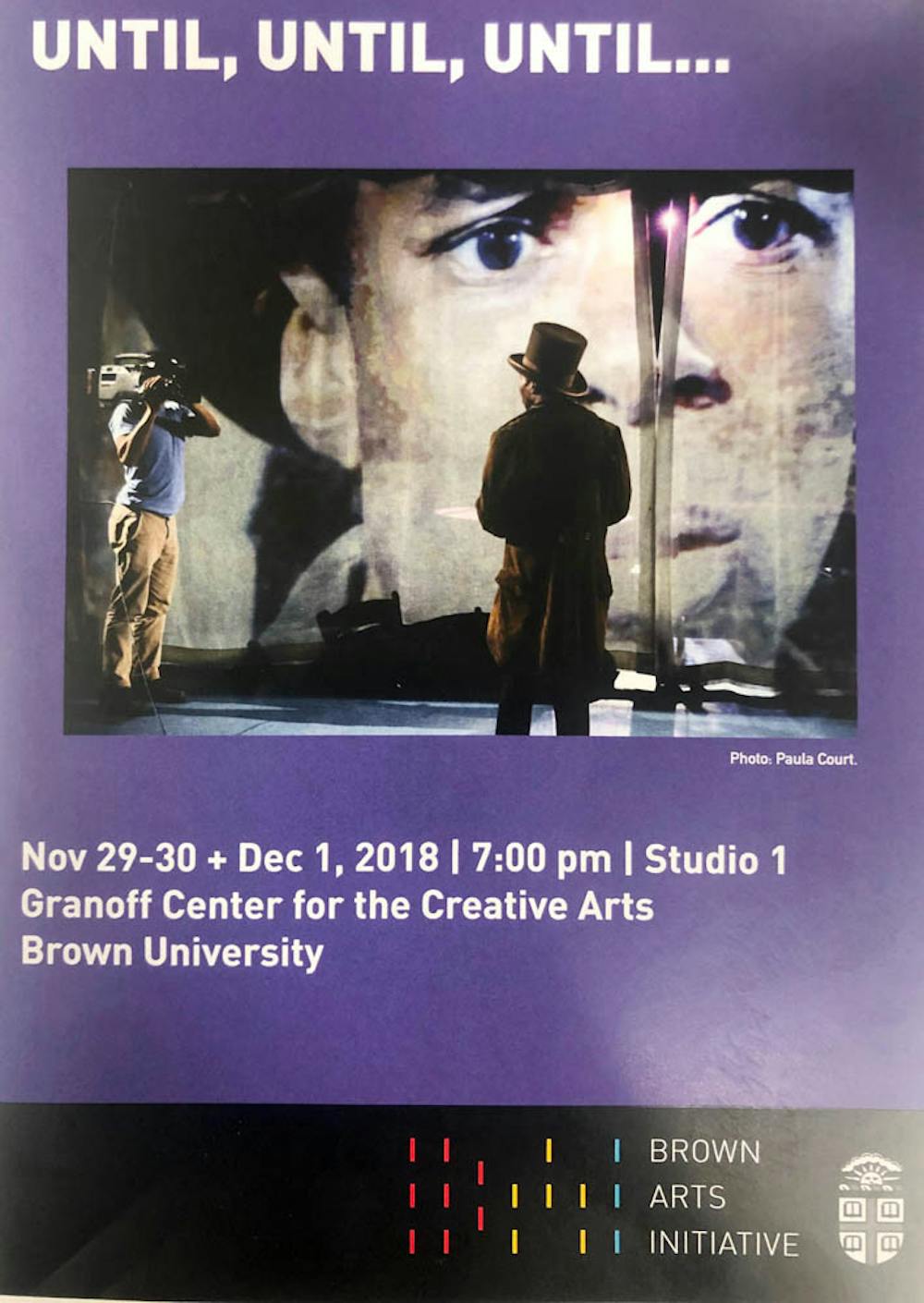

At the end of the song, Lawson thanked the audience and stood pensively for a few long moments before exiting the curtained stage area, leaving the audience waiting for a cue to signal the end of the performance. After some time, a camera operator panned across the faces of the audience, replacing the projected images of the 1981 inaugural ball attendees on the stage curtains during the final song.

Friday, the audience sat for nine silent minutes before one member finally left. His exit cued a shift in the music and lights, indicating that the performance had concluded. Thursday, it took only about two-and-a-half minutes for the first audience member to leave, Arceneaux said.

“Until, Until, Until…” featured varied multimedia technology including projected images and videos as well as music and special audio effects. These techniques “created this world in which we as audience members could sort of transgress multiple boundaries. … At one point, we were an external Brown audience watching the play, and then at another point, we were in a sense transported and had become the audience at Ronald Reagan’s inauguration,” said Butch Rovan, faculty director of the Brown Arts Initiative.

Arceneaux utilized the multimedia technology to invoke ideas of memory, trauma and reflection. “I decided to tell the story not from a historical perspective, but from the way that Ben Vereen remembers it — which is as a series of traumas,” he said. “So in that regard, I’m being faithful to the feelings of the memory, without trying to do what I think is essentially impossible — which is to tell it exactly as it happened.”

Arceneaux first saw Vereen’s 1981 performance on a VHS tape as part of a documentary on black artists in 2007. The documentary included Vereen’s entire performance, leaving Arceneaux unaware of the negative professional and psychological ramifications that the televised version had on Vereen’s life and work. That is, until he encountered Vereen himself at a birthday party.

“He was very welcoming,” Arceneaux said. “But when I mentioned his performance in 1981, he shuddered. I could tell that I’d struck a nerve. But I didn’t know why.” Based off the artist’s actual interactions with the performer, “Until, Until, Until…” includes a scene where Arceneaux, playing himself, sits with the actor playing Vereen in his living room, watching the original footage.

Ultimately, Arceneaux said he hoped his work could teach his audience “something about the world.” He watched the individuals in the audience struggling with the decision to leave, realizing that “at some point you then start asking yourself, well is this story over yet?” With that questioning comes a transformation: Audience members look around at the individuals that surrounded them and realize that their next move had become a group decision.

“It’s like this idea of going from ‘I’ to ‘we.’ People start to figure out how to negotiate that space. … It’s kind of like a little tiny microcosm of society that happens inside (the curtains),” Arceneaux said.

“The amazing thing about the piece is that it doesn’t offer closure. You leave, and it doesn’t end. As an audience member you’re left to just try to create your own closure — and maybe it doesn’t ever end for you,” Rovan said. “The issues that it raises are still things that we are grappling with today.”

Rovan stressed the ability of this experimental work to remain accessible to a wide audience. “This piece worked on so many different levels — it was visceral, it was cerebral, it was contemplative, it was very emotional,” he said.

Arceneaux hopes to continue performing the piece around the country. While it has toured nationally since its creation in 2015, Arceneaux said the 2016 election “changed my resolve to tour it and show it more, considering this very surreal political reality that we’re in where entertainment and politics have become so intertwined.” He added, “a story like this allows us to see the truth in a way that I think telling the story straight couldn’t do.”

He hopes that they can bring the performance to as many politically divided and red states as possible, where the piece might cause controversy but also might inspire people to reconsider their views. This latter possibility gives him hope that the performance “might shift their sense of justice,” he said.

Correction: In an earlier version of this article, the caption and subheading misspelled the name of artist Edgar Arceneaux. The Herald regrets the errors.