A study published last week identified a new possible explanation for the difference in neurological responses to early life stress between men and women.

The study, conducted on mice, showed that females exposed to early life stress saw a decline in cognitive ability when performing certain tasks and had lower cell density in the orbitofrontal cortex, the brain region responsible for decision-making. The male mice in the study, however, were not affected, despite being exposed to the same stress.

Though the study used mice, there is strong evidence to suggest that the findings can be applied to humans, said Kevin Bath, assistant professor of cognitive, linguistic and psychological sciences. “Women are two times as likely to develop depression or (post-traumatic stress disorder) from stressful or traumatic events in childhood. We’ve known this for a long time, but this is the first time we can show the mechanism behind differences between how men and women might respond to stress differently,” he said.

The study was conducted with two groups. In the control group, mice pups were raised under normal conditions, with the mother taking care of their young from birth. In the early life stress group, the pups and their mothers were given an area with limited nesting materials for one week four days after birth, “equivalent to one year of being in a high-stress environment,” Bath said. Afterwards, the mice in both groups were tested on their cognitive abilities using a variety of rule-learning tests.

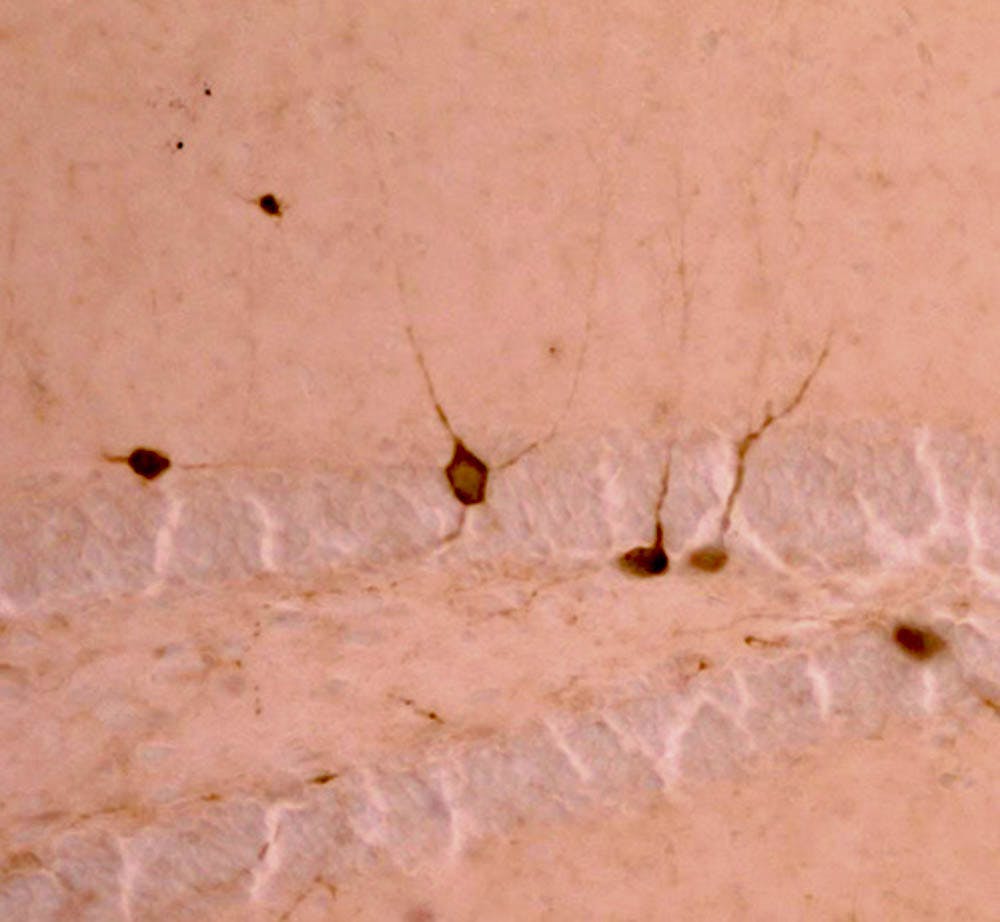

Researchers found that females exposed to early life stress were more likely than males to be impaired in rule-reversal learning. In this task, mice were conditioned to associate food with a particular scent, such as lavender, and would then have to associate it with a different scent, like lemon, said Haley Goodwill PhD'18, lead author of the study. Additionally, “this was compounded by the loss of parvalbumin interneuron cells,” a type of neuron in the orbitofrontal cortex that is important for cognition and flexibility, and sensitive to stress, she said.

In the second part of the study, researchers used optogenetics, a technique that uses light to manipulate cells, to turn off parvalbumin interneuron cells in the healthy mice, which caused them to have the same impairment as the early life stress female mice. “That indicated to us it could be these fine-tuning neurons that affect this (response to) stress,” she said.

“This is a very new model of stress, … (but) the results of depression (for mice) map very well onto the human literature,” said Gabriela Manzano Nieves GS, another researcher involved in the study. Though the particular model of early life stress in mice used in the study has only been in scientific literature for “about 10 years or less,” this new study leads researchers in a promising direction, she said.

The researchers said that future studies should investigate the mechanisms behind the sex differences in parvalbumin cell density that might be causing the female mice to be more susceptible to stress. There are many potential explanations for these differences in early-life development, such as chromosomal sex difference, sex hormone differences or higher maternal nurturing of males compared to females after stress, Bath said.

Francis Lee, chair of the department of psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical College, who is unaffiliated with the study, believes the research is a promising step toward advancing our understanding of the brain. “It’s conceptually novel. People don’t normally think of the orbitofrontal cortex when thinking about depression in the brain,” Lee said. “This finding could have great potential in informing neuroimaging studies with regards to depression.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article stated that stress responses in mice were found to vary between genders. In fact, stress responses in mice were found to vary between sexes. An earlier version of this article also identified Haley Goodwill as a graduate student. In fact, Goodwill received her PhD in 2018. The Herald regrets the errors.