This article is the second in a 50th anniversary commemorative series on the 1968 black student walkout.

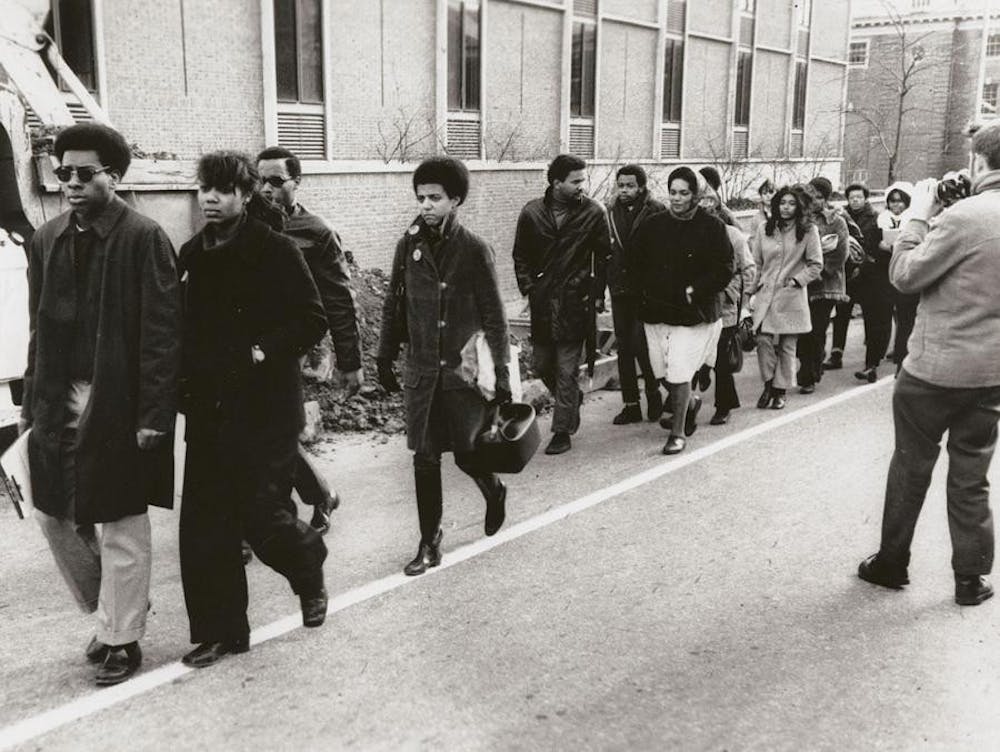

The women of Pembroke College who staged one of the largest student walkouts in University history in December 1968 chose to protest publicly only after exhausting all other options, said Ido Jamar ’69, a Pembroke graduate who helped organize the walkout 50 years ago.

“It wasn’t as though one day we woke up and said the University has to (follow our demands). We’d been working with the University to try to increase admission, but it had been piecemeal,” she said.

The women had been meeting and negotiating with University administrators since the previous spring to improve the admission and retention of black students. During their conversations, black students from Brown and Pembroke presented administrators with a list of demands that included measures such as hiring a black admissions officer, increasing the enrollment of black students to a minimum of 11 percent, waiving the application fee for black applicants and allocating more funding for scholarships.

But the University was reluctant to implement these changes, said Kenneth McDaniel ’69. “It got to the point where they weren’t moving; we’ve done this, we’ve proven this and they seem to be continuing to find excuses or reasons why they can’t do the next step,” he said. “We overcome that hurdle, then another hurdle gets thrown up.” The University cited a lack of qualified candidates, a low number of applicants and a limited amount of financial aid as barriers to increasing black student enrollment, he added.

“It was basic representation in the society. … We grew up in black communities, we (knew) that there were other students who (could) do the work and (could) do well here,” said Bernicestine McLeod Bailey ’68, a trustee emerita of the University. “However, no one (had) reached out to them, no one seemed to know about them.”

By spring 1968, students at Brown had been organizing recruitment efforts to increase black student admission, McDaniel said. “We’re all going out and recruiting, a number of us are writing letters, we’re having these African American weekends where potential candidates are coming up and rooming with folks,” he added.

When it became clear that the conversations would not result in policy changes in the near future, student activists considered actions they could take to force change. As students across the country organized marches and occupied buildings to protest institutionalized racism four years after the adoption of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the students at Brown and Pembroke determined that a walkout would best serve their goals, Jamar said.

“We chose to separate and disassociate ourselves from the campus until our concerns were addressed. That does not mean that our protest was any the less intense or effective from our point of view,” said Glenn Dixon ’70. “We wanted to choose the appropriate form of protest for the Brown campus and community that (could) involve the highest number of … students who had similar kinds of concerns.”

While the walkout was the result of a breakdown in negotiations between students and administrators, it also highlighted the alienation many alums interviewed by The Herald felt at Brown at the time.

Overcoming exclusion and isolation

At the time of the walkout, a total of 87 black students attended Brown and Pembroke. These students faced institutional and personal challenges that their white counterparts did not.

For instance, some black students were dissuaded from pursuing their academic interests when they arrived on campus. “Many of us were counseled out of the majors that we initially came in for. In retrospect, I think it was because they thought we couldn’t handle it,” Jamar said.

“I came in as a pure math major — I had won competitions in mathematics, I had almost a perfect score on the SAT in math, but I was counseled out of being a pure math major,” she added. “That was your first meeting at Brown; it was someone trying to say, ‘I don’t think you can handle pure math.’ … There’s nothing on paper that should have said that … and I really think I would have enjoyed pure math better than applied math.”

Along with confronting institutionalized racism, some black students faced ostracism and condescension from their white peers, Jamar said. “It was the assumption … that we were admitted with lesser qualifications. We constantly had to justify that we had a right to be here intellectually,” she said. “A lot of us were given roommates who were clearly uncomfortable having a black roommate. … Having to (be) close (to) … people who were uncomfortable with you was new to a lot of us.”

“There was no faculty of color, no administrators of color, it was a totally white environment,” McLeod Bailey said. “The only black women that we saw were the maids … that would clean our rooms.”

Living on College Hill was an isolating and foreign experience in itself. “The food has none of the taste that you’re familiar with. There’s none of the music that you would typically hear,” McDaniel said.

“There was a fair amount of talk among black students about where in the world you could go to get a haircut that looks like a haircut,” he added. “If you wanted to find anything that reminded you of yourself or where you were from, you’d have to find something out in the city.”

As black students struggled to feel accepted on a predominantly white campus, they also faced challenges in building a community of their own. Given the limited number of black students at the University, it was difficult “to establish some sense of community (with) shared values and upbringing and (a) shared cultural experience. There was a certain amount of alienation, being such a small portion of such a large community,” Dixon said. “We (wanted) to work toward finding cultural areas of mutual background and experience. … When we arrived at Brown, those opportunities were minimal, if in existence at all.”

This struggle to create a more robust sense of community “was in part what precipitated the walkout itself,” Dixon said. During discussions with the administration before the walkout, the students requested “an increase in African American students. … We sought similar goals for employment at the University at all levels. We also sought to have a space where we could all come together and meet, ” he added.

National racial unrest

Around the time that students planned the walkout, the United States was embroiled in racial unrest that manifested on college campuses, at athletic events and in political gatherings.

At Columbia, students protested the University’s ties to weapons research by taking over several buildings on campus and briefly holding a dean hostage by using furniture to prevent him from leaving his office. The students of Columbia’s Afro-American Society also occupied an administrative building for a week to oppose a planned gymnasium in Harlem’s Morningside Park. They saw the proposed building as a racist and segregated structure that encroached on the space of Harlem residents, according to the New York Times. Eventually, the protest was broken up by 1,000 police officers, leading to over 700 arrests of student protesters and over 100 injuries, according to the television network History.

In March 1968, over 2,000 students at Howard University occupied an administration building for three days to demand more influence in student discipline and curriculum.

In some cases, student protests ended in violence. At South Carolina State University, police injured 28 students and killed three others who were protesting a segregated bowling alley in Orangeburg, South Carolina in 1968.

Alongside widespread college campus protests, the 1960s saw the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, the height of the Vietnam War, the Chicago Police riot at the Democratic National Convention and the national anthem protest at the Mexico City Olympics.

With heightened racial tensions across the country serving as the backdrop, Brown and Pembroke students staged their walkout, cementing their place in the story of student activism against racial inequality in 1968.