The Admission Office formed a working group focused on expanding access to the University for first-generation and low-income students, according to Dean of Admission Logan Powell. The working group emerged from discussions between the Admission Office, the Undergraduate Council of Students and student leaders of the #FullDisclosure campaign, which called on the University to reexamine its legacy admission policy, Powell said.

These discussions followed the campus-wide referendum on legacy preference last March, which asked students whether the University should “charge a joint committee of students, alums and administrators to reexamine the use of legacy in the admission process,” said Shawn Young ’19.5, a coordinator of the #FullDisclosure campaign at the University. The referendum passed with 81 percent of the vote, The Herald previously reported.

The working group, which was formed at the start of this semester, will not reexamine the use of legacy preference in the admission process, Powell said. “The working group is really entirely focused on first-gen and low-income recruitment, admission and yield,” he added.

Young still wants the University to scrutinize its legacy admission policy. “There (are) certainly concerns that we should have with it,” he said. But “we’ve never said that legacy students were unqualified to be here.”

No student is ever admitted simply because their parent attended the University, Powell said. Instead, legacy status is one of many “tie-breakers” that the Admission Office considers as a positive attribute of an applicant. Being a first-generation student is another “tie-breaker” that can help an applicant, he added.

Though the working group has no focus on legacy preference, Young believes the current working group’s broader goal of expanding access is productive. “The logical next step after the (#FullDisclosure) campaign was to talk about how we could work together to make a working group that doesn’t just look at the admission process, but overall how Brown can do better at increasing access for (first-generation and low-income) students,” he said.

Previously, Young emphasized that #FullDisclosure did not treat examing legacy admission and making the University more accessible to first-generation and low-income students as unrelated goals. “Powell makes it seem as if #FullDisclosure is solely about increasing access for first-generation and low-income students,” he wrote in an email to The Herald in March. “I’d like to make it perfectly clear that #FullDisclosure is about ensuring equal opportunity for everyone and making this University the best it can be.”

The representatives of UCS and #FullDisclosure who met with Powell last spring were interested in both reexamining legacy preference and expanding access for first-generation and low-income students, Powell said. But he concluded that the two issues are unrelated. “We can continue to recognize sons and daughters of Brown graduates, and at the same time we can continue to find ways to admit more first-gen students,” he said. “Really, they’re just not connected.”

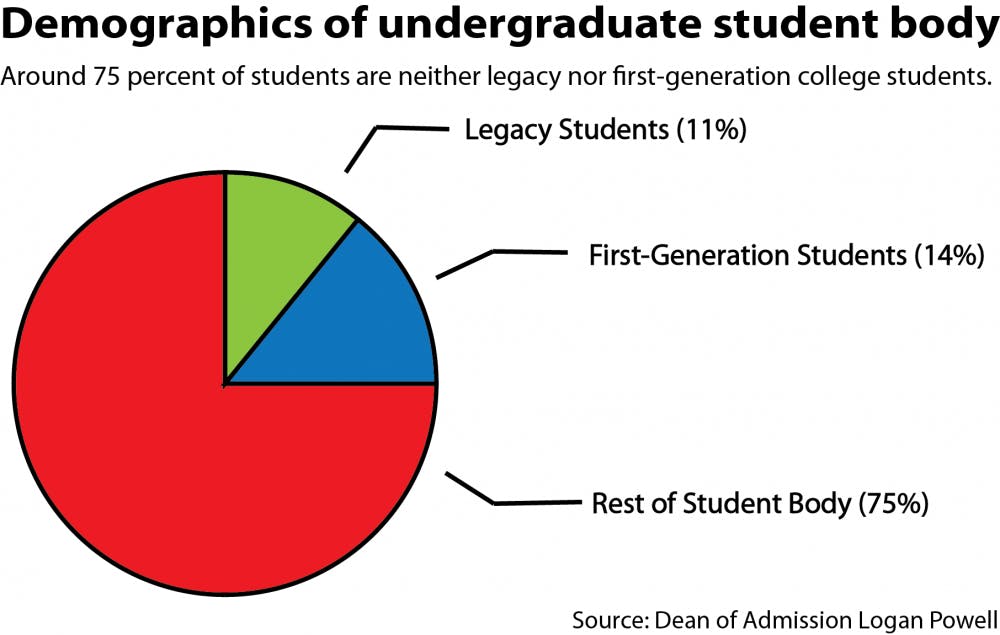

Legacy students make up about 11 percent of the student body while first-generation students comprise about 14 percent, Powell said. “The combination of those two groups is a quarter of the student population,” he added. Since about 75 percent of students are neither legacy nor first-generation, admitting legacy students does not force the University to admit fewer first-generation students, Powell said.

In a Nov. 8 column titled “Don’t let the discussion of legacy admission die,” Opinions Editor Connor Cardoso ’19 wrote that “unless Brown is exceptional in its approach toward legacy applicants, it is, at the end of the day, creating space for legacy students at the expense of low-income and first-generation students because there are only a finite number of spaces.”

“If we had no legacy policy whatsoever, it wouldn’t necessarily mean that there would be an increase in the first-gen students we attract,” Powell said. “We have to do something specifically around attracting first-gen students to attract first-gen students,” which is the focus of the working group.

Though Cardoso acknowledged the University’s commitment to increasing access in his column,“trying to disentangle the University’s legacy admission policy from the broader discussion of equal access in admissions is impossible, and the University working group should resist this urge,” Cardoso wrote. “Abolishing legacy admission is a necessary condition for cultivating genuine socioeconomic diversity in the student body.”

Members of the working group include two students, two professors and two representatives of the Admission Office, including Powell. The students on the working group were nominated by UCS President Shanzé Tahir ’19, Powell said. One member of the group, John Friedman, associate professor of economics and international and public affairs, has done research on social mobility and college access for low-income students, Powell added.

A paper Friedman published last year studied upward mobility for low-income students at every college in the United States, Friedman said. “What we found was that consistently across elite private institutions, there were just not that many kids from low-income families,” he said.

At the typical Ivy League school, there are more students from the top one percent of the income distribution — families that earn over $650,000 per year — than there are from the bottom 60 percent — families with annual income under $65,000, Friedman said. The University is roughly consistent with this socioeconomic distribution of students, he added.

In 2013, the latest year for which Friedman has data, about 4 percent of students at the University came from the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution, he said. Friedman suggested the University try to increase enrollment of low-income students to about 7 or 8 percent of the student body, mirroring the composition of students at the University of California at Berkeley, which enrolls 7.5 percent of students from the bottom 20 percent.

“It’s probably not feasible to get there immediately,” Friedman added. “I hope that (the working group) can find some ideas that will make a difference.”

The working group is trying to find out what schools like UC Berkeley do differently to attract, admit and enroll more low-income students, Friedman said. “We can try to understand what they’re doing and try to learn from it,” he added.

Legacy admission is an institutional priority that the Admission Office does not control, Powell said. He hopes the group can finalize its recommendations for changes and initiatives that the Admission Office can implement by the end of December.