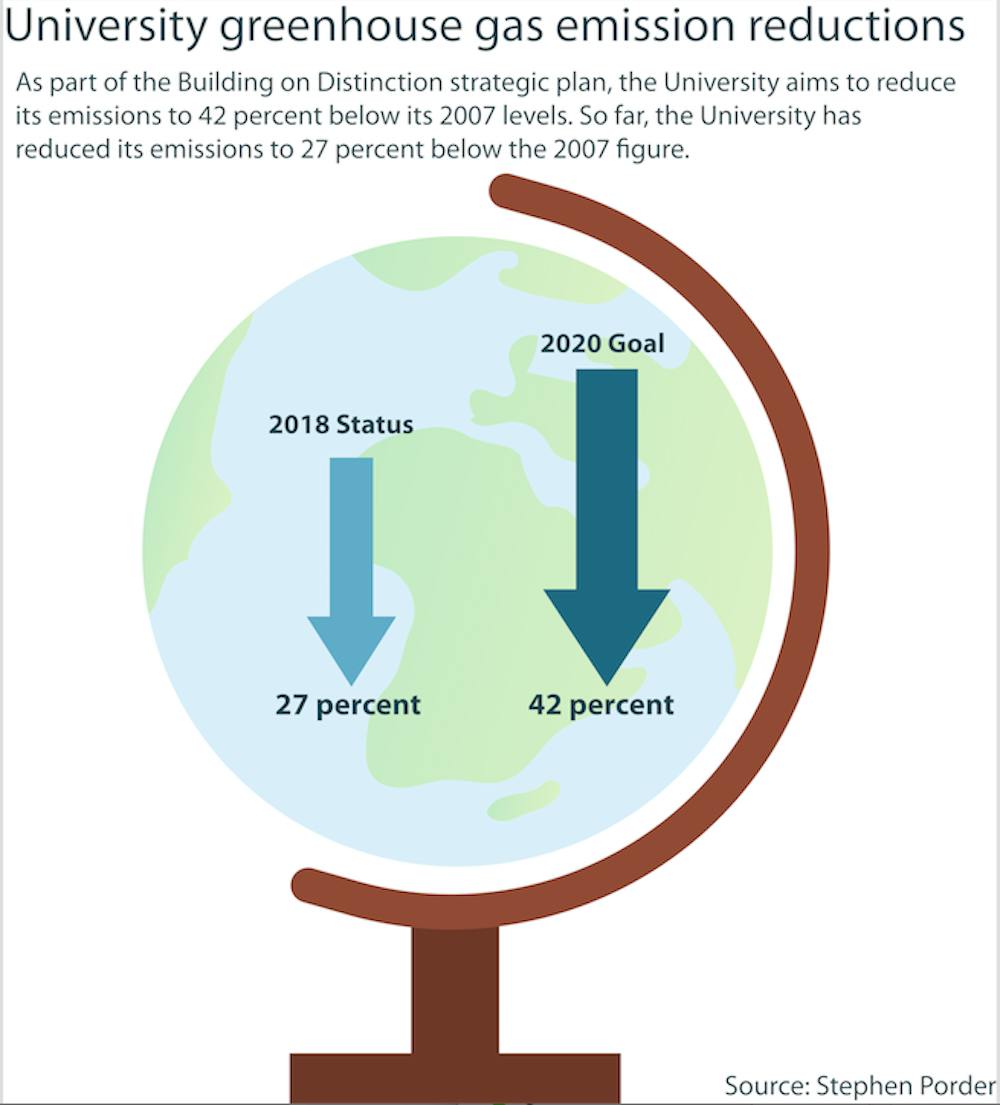

The University is on track to meet its goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions to 42 percent below 2007 levels by 2020, according to Stephen Porder, assistant provost for sustainability and associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology.

The University began its current mission to cut greenhouse gas emissions in 2008 under the leadership of former President Ruth Simmons. This year, President Christina Paxson P’19 seeks to make the University “a model of sustainability,” she wrote in a Sept. 3 University-wide email.

“Currently, the University has reduced its emission by about 27 percent below 2007 levels,” in line with the goals outlined in the 10-year strategic plan “Building on Distinction,” wrote Jess Berry, director of sustainable initiatives, in an email to The Herald.

“Globally, the activities over the past 100 years have put the Earth on a trajectory toward a tipping point that we are fast approaching,” making it essential to mitigate some of the effects of climate change, Berry wrote.

As part of the effort, Porder is determining how to reduce the University’s greenhouse gas emissions, which are classified under three scopes. Scope one emissions stem from on-campus combustion, such as the natural gas burned in the current central heating plant. Reducing these emissions will “require the electrification of campus heating, … which is currently provided by fossil fuel combustion,” Porder wrote in an email to The Herald. This process is “a major engineering, logistical and financial challenge, but one I am eager to address.”

Scope two emissions reflect combustion done for the University by outside organizations, like electricity production. To address these concerns, “we are moving towards purchasing renewably-generated electricity for Brown,” Porder wrote.

Scope three emissions are those that “occur as a result of Brown’s activity” but do not fall under the previous categories, including emissions from “faculty, staff and student travel” as well as “the production of goods that Brown purchases,” Porder added. This year, he will chair a committee that aims “to consider how to quantify and reduce Scope three emissions,” which were not considered in the University’s 2008 goals and are difficult to quantify.

Of the 27 percent reduced so far, “the largest reduction” results from the Thermal Efficiency Project, which focuses on the University’s switch “from heating oil to natural gas at the central heating plant,” Porder wrote. This Scope two project will convert the current campus central heating plant from a steam-powered system to a hot water-powered system, Berry wrote. The completion of this three-year project will result in “annual savings of over $1 million in fuel costs and a reduction in (greenhouse gas) emissions by 5,000 tons,” she added. So far, the University has completed “the initial planning, equipment ordering and contractor staging of the first year of work,” Berry wrote.

The total cost of the Thermal Efficiency Project is $24 million, according to a University press release. Beyond this expense, the University invests about $3 million annually “in projects to increase efficiency on campus, reduce utility cost and decrease our greenhouse gas emissions,” Berry wrote.

Cutting greenhouse gas emissions is not just a financial challenge, but a technical one as well. Students, staff, faculty and administration are in the process of developing a sustainability master plan, which will likely take a year to complete, said Leah VanWey, associate provost for academic space and professor of sociology and environment and society.

Along with trying to limit greenhouse gas emissions, the University strives to practice sustainability across campus by looking into its academic operations, including transportation, parking and water use, VanWey said.

VanWey wants sustainability to become a campus conversation. “I would like to see it infused as a core value throughout all of our activities” following the example of the Diversity and Inclusion Action Plan, VanWey said. While the steps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions are clear, integrating sustainable practices on campus is a more abstract mission, she added.

“We know we need to get to (net) zero emissions or we’ll have catastrophic climate change,” VanWey said.

VanWey and Porder have been leading the effort to define the University’s post-2020 plans, Berry said. While the conversations are just beginning, the future goals will be based on “what is feasible and possible given our facilities and mission,” VanWey said.

Climate change is widely considered the greatest danger to humanity today, Porder wrote. “In my opinion there has never been a greater challenge or a more urgent one.”