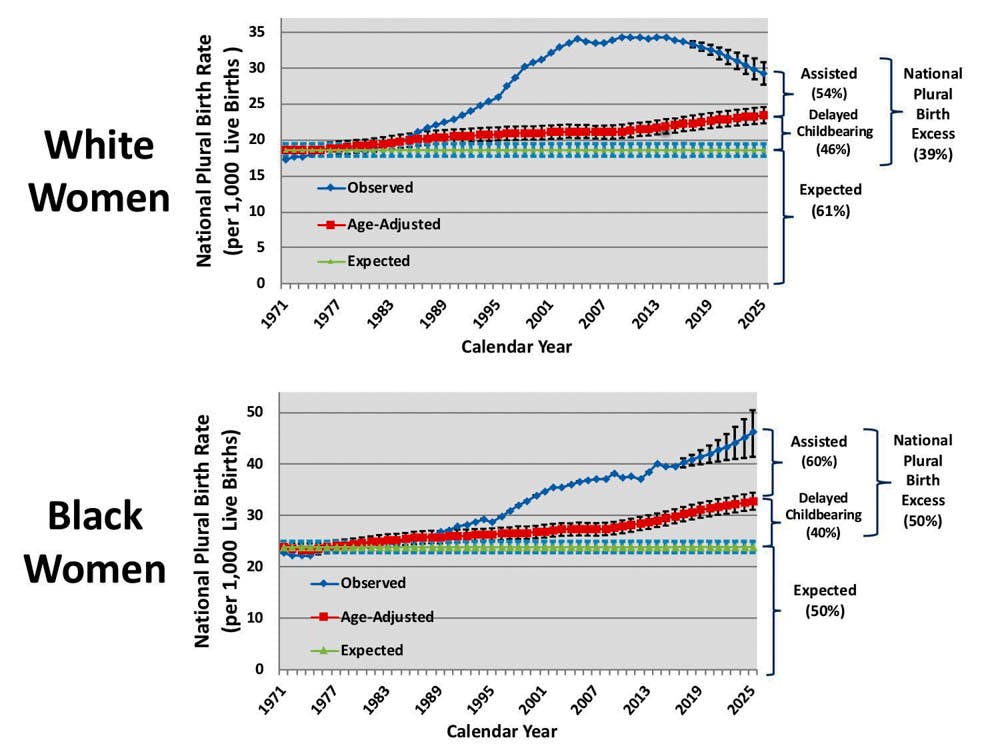

A new study by University professors shows older women are more likely to give birth to more than one baby at a time due to the aging reproductive system.

The researchers compared reproductively active white and black women ages 15 to 19 and reproductively active white and black women ages 35 to 39 and found that the older population experienced an increase of multiple births — having twins, triplets and so on, according to the study. While ten out of 1,000 women in the younger population had multiple births, 30 out of 1,000 women in the older population had multiple births, said Roee Gutman, associate professor of biostatistics.

“As women approach their mid-thirties and beyond, the incidence of (multiple births) increases threefold in the context of Caucasian women and fourfold in the context of African-American women,” said Eli Adashi, professor of medical science. “We know that in some communities in Africa that have been studied there seems to be a higher incidence of multiples which may well be genetically determined but has not been fully elucidated.”

Thirty-five to 39 years old “is about the time when the reproductive system in women is getting closer to the point where reproduction is no longer operational,” Adashi said. “There are probably subtle imperfections in the way that ovulation is controlled, so instead of ovulating a single egg, women in these age groups are increasingly ovulating more eggs,” he added.

“Since women’s fertility declines starting at a surprisingly early age, around 30, the shift towards delaying childbearing results in more challenges in conceiving, more use of assisted reproductive technologies and more multiple births,” wrote David Savitz, associate dean for research, professor of obstetrics and gynecology, professor of pediatrics and professor of epidemiology, in an email to The Herald.

“Today women, for good reasons, delay starting a family, and this phenomenon is bound to increase,” Adashi said. “The biggest problem with multiple pregnancy is premature labor. When you get to twins and triplets and beyond, the capacity to accommodate them throughout gestation is increasingly compromised. The babies rarely reach term simply because humans were not designed to carry multiples,” he added.

“Ninety-eight to 99 percent of all births in the United States are singletons,” Adashi said.

“I think we need to focus on reducing this possibility (of multiple births). This is a very unhealthy state for the fetus and pregnant women,” said Sangshin Park, assistant professor of pediatrics.

Prior to the study, medical researchers already knew that childbearing at later ages was linked to multiple births, but it was not recognized as a main factor, Adashi said.

In the past, the occurrence of multiple births was attributed to drugs that increase ovulation, Gutman said. Before ovulation-inducing drugs were approved, there was a parabolic relationship between age and producing twins. This shows that age has been a factor even without the in-vitro fertilization practices currently, he added.

“Our study shows these fertility-promoting therapies should not be the only one to shoulder the blame,” Adashi said.

There are other factors related to age that could cause multiple births to occur, including previous pregnancies and obesity, but these need further research, Gutman said.

“Many couples want to round out the family, having another girl or another boy,” Adashi said. “That decision could lead to much more than one bargained for.”

“Because the reasons for delaying childbearing are personal and take many factors into consideration, I don’t think this suggests women be discouraged about the consequences of delay but rather be informed to make the best judgment for themselves,” Savitz wrote.

“This is an interesting, unusual perspective on an unintended consequence of delayed childbearing,” Savitz added. “On a national level, this has implications for reproductive health services to meet the needs of older mothers and more multiple births.”