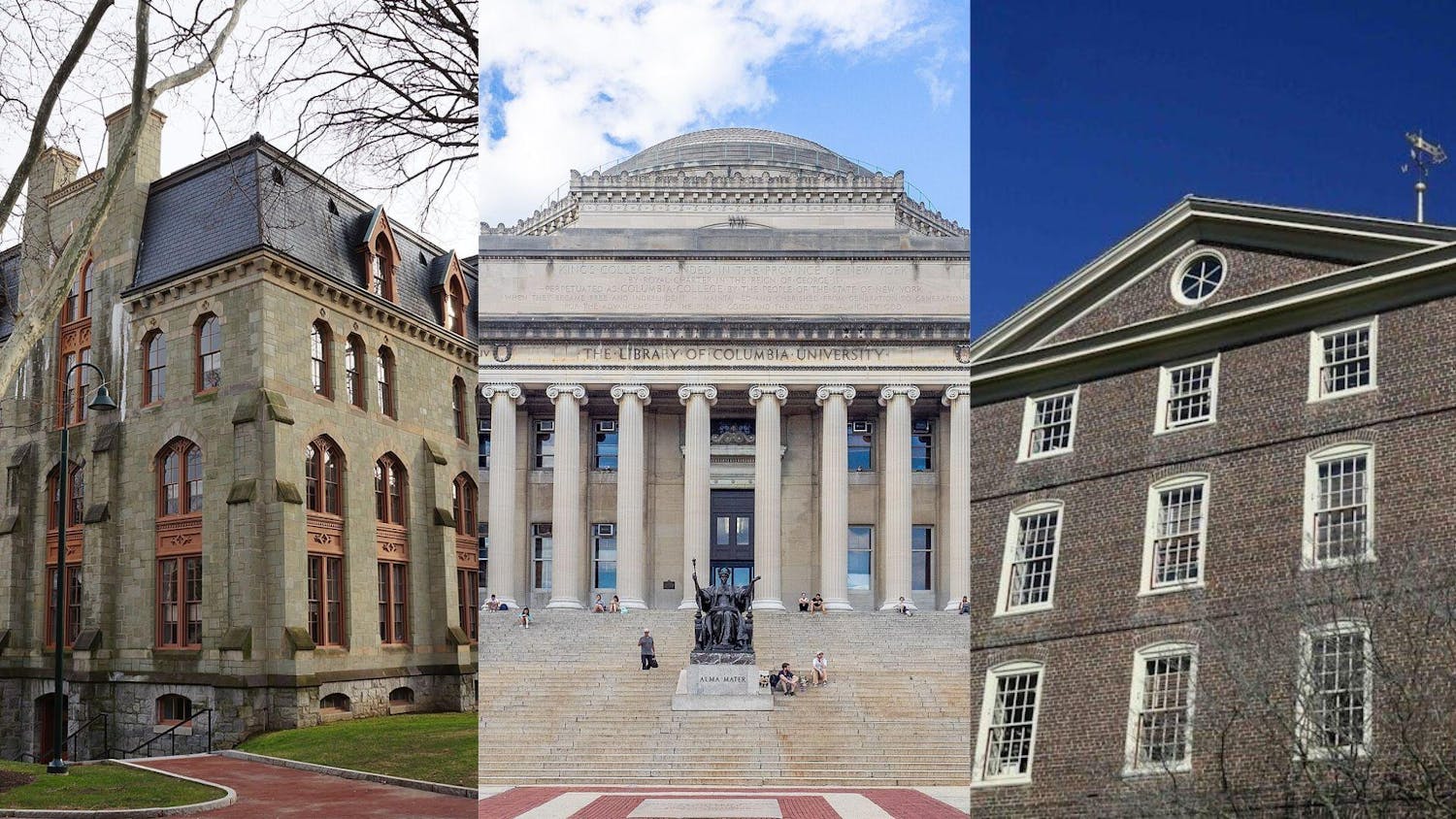

Brown was one of 16 highly selective schools to sign an amicus brief July 30 supporting Harvard’s consideration of race in admission decisions.

Harvard is currently being sued by the organization Students for Fair Admissions for allegedly discriminating against Asian American applicants. Much of the evidence they reference suggests white applicants benefit from this discrimination. In November 2014, Students for Fair Admissions filed a suit against Harvard in the District Court of Massachusetts alleging Harvard discriminates against Asian American applicants in violation of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prevents “any program or activity” that receives federal funds from discriminating on the basis of race or ethnicity. The suit’s verdict could be used to further challenge race-conscious admission nationwide, if brought before the Supreme Court.

"We at Brown will do everything in our power to advocate against changes to laws or policies that would undermine our ability to build a diverse community of outstanding students,” said President Christina Paxson as quoted in a Brown news release Aug. 1. “Through our race-conscious admission practices, Brown assembles the diverse range of perspectives and experiences essential for a learning and research community that prepares students to thrive in a complex and changing world,” she added.

The Harvard lawsuit

The plaintiffs make four contentions about Harvard’s admission process in their court filings: Harvard discriminates against Asian Americans the way it once discriminated against Jewish Americans; the university engages in racial balancing by pitting members of ethnic groups against each other; race is not just a “plus factor,” one of many factors considered in the application process, but rather a defining feature of applicant evaluation; and Harvard uses race when race-neutral alternatives could be used to achieve diversity.

The amicus brief that Brown joined was released six weeks after Students for Fair Admissions submitted more than 160,000 student records before the federal court in Boston. Two statistical analyses of these documents reached conflicting conclusions with regard to whether Harvard discriminates against Asian Americans. David Card, professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley, found no evidence of discrimination in his analysis for Harvard, while Peter Arcidiacono, professor of economics at Duke University, found that there was evidence of discrimination in his analysis for the plaintiffs.

Harvard criticized Arcidiacono’s analysis, claiming it skewed the results and excluded data, according to a news release. In a separate amicus brief, five economists, including Glenn Loury, professor of social sciences at Brown, endorsed Arcidiacono’s analysis. Loury could not be reached for comment.

The lawsuit against Harvard addresses two separate issues together: whether Asian American applicants are discriminated against to benefit their white peers and whether any consideration of race in admission decisions is legal and consistent with the Civil Rights Act. The amicus brief that Brown co-filed may influence and inform the court’s final decision; in previous court cases related to affirmative action, justices have cited amicus briefs in their decisions.

The specific charge of discrimination against Asian Americans adds a “unique twist” to this court case, according to University of California, Los Angeles, Professor of Education and Asian American Studies Mitchell Chang. But race-conscious admission has been challenged multiple times in court as a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Over the last decades, a few cases concerning public universities have resulted in landmark Supreme Court decisions. Each time, the Supreme Court re-evaluated and reaffirmed the legality of race-consciousness in admission, though in some instances by a narrow margin.

This is “as tough of a case as you can get,” said Indiana University Professor of Law Kevin Brown. Usually in affirmative action cases, “you’re thinking about blacks and Latinos, but this really does flip the script” by shifting the focus to Asian Americans, he added. In addressing affirmative action and discrimination against a racial minority together, this case reframes affirmative action by arguing that it hurts rather than helps a minority.

Discrimination against Asian Americans

The lawsuit considers admission practices implemented at Harvard to discriminate against Jewish American applicants beginning in the 1920s. It traces these practices to allege comparable present-day discrimination against Asian Americans. While Students for Fair Admissions focuses on holistic race-conscious admissions specifically at Harvard, they also reference admission data from other selective institutions. The case “could have been brought against any highly selective institution that uses holistic admissions practices," wrote Michele Moses, associate vice provost of faculty affairs at the University of Colorado, Boulder, in an email to The Herald.

Asian Americans made up 5.8 percent of the population in 2011, according to the US Census Bureau. Harvard enrolled nearly the same percentage of Asian Americans each year between 2003 and 2013, according to Students for Fair Admissions. Asian American enrollment fluctuated between 15 percent and 20 percent of the entering class during these years, according to the filings. Other Ivy League institutions appeared to enroll Asian American students in a similar range of percentages between 2007 and 2013, as though they were filling a fixed number of seats by race, according to the filings.

Racial quotas were deemed illegal by the Supreme Court in 1978 in the case of Regents of the University of California v. Bakke.The same ruling stated that race-conscious admission that does not rely on racial quotas does not violate Title VI of the Civil Rights Act.

In the amicus brief, Brown and the other institutions make no explicit mention of Asian American applicants. Nevertheless, the brief rejects the suggestion that the signatories employ a quota system or racial balancing in their established admission practices. “No seats in the class are reserved for applicants of any race or ethnic background, nor are applicants of any race or background limited to a certain number of places,” the brief states.

Students for Fair Admissions argue that Asian Americans are held to a higher academic standard than other applicants. Asian American applicants had to score about 140 points higher than similarly qualified white applicants on the SAT to be accepted at elite schools, according to a 2009 study by Princeton Professor Thomas J. Espenshade and co-author Alexandra Radford cited in their court filings. The court documents and statistical analysis for the plaintiffs suggest that in the case of Harvard, one reason for this kind of admission disparity is that Asian American applicants are, on average, rated lower than white applicants in a “subjective personal component,” said Ben Backes, senior researcher at the American Institutes for Research. Harvard contests this analysis.

“There’s been a sense in the Asian American community for a long time that the deck is stacked against them, and many are going to point to the evidence in this case and say, told you so, or we knew it all along,” Backes said. “For them it is very much a question of fairness.”

A case considering Asian American discrimination in holistic admission was “one that people who look at affirmative action knew was coming,” and was 10 to 15 years in the making, Brown said.

As early as 1990, the Office of Civil Rights for the Department of Education found that Asian Americans were being admitted at “a significantly lower rate” to Harvard despite being “similarly qualified” to white peers between 1979 and 1988, though the probe attributed the disparity to the use of legacy admission policies.

During this period, Brown reformed its own treatment of Asian Americans in admission, acknowledging that its admissions policies had treated Asian American applicants "unfairly,” according to a 1990 academic article on Asian American admissions by Dana Takagi, professor of sociology at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

In the last couple of years, Asian American groups have submitted multiple civil rights complaints about discrimination in admission to elite universities. In 2016, the Asian American Coalition for Education filed one such complaint against Brown, Dartmouth and Yale to the Civil Rights divisions of the U.S. Education and Justice Departments. “The 2016 AACE complaint was dismissed by the Department of Education and Office for Civil Rights shortly after it was filed,” wrote Director of News and Editorial Development Brian Clark in an email to The Herald.“We took no action because the complaint had no merit. Our admissions practices are inclusive of diverse populations and do not discriminate against any racial or ethnic group,” he added.

Contesting affirmative action policies

While the claim that Asian American applicants are discriminated against to the benefit of white applicants is not exactly new, the lawsuit also lays blame for this contention at the doorstep of race-conscious admission policies. Race-consciousness in admission “still doesn’t explain why white applicants are getting an advantage over Asian American applicants,” allegedly, Chang said.

In the brief, universities emphasized the importance of race-conscious admission in achieving and maintaining diversity to provide students with the a comprehensive educational experience. The brief specifically references Brown’s mission statement, along with Dartmouth’s, to link their objective of preparing students for life with creating a diverse campus.

The brief states that this diversity would not be possible if race-neutral measures were implemented. “Amici consider race and ethnicity as one factor among many in order to better understand each applicant and the contributions he or she might make to the university environment,” the brief reads.

The right to set their own admission practices, amici argue, is “protected by the First Amendment and entitled to deference from the courts.” Prohibiting universities from considering race in admission would constitute “an extraordinary infringement on universities’ academic freedom,” the brief adds.

Most recently, the Supreme Court clarified the standards for evaluating the constitutionality of race-conscious admission in the case Fisher v. University of Texas. The Court addressed Fisher twice: Fisher I in 2013 sent the case back to a lower court to consider with “strict scrutiny” whether race-conscious admission was applied with a limited scope. In Fisher II in 2016, the Court held in a 4-3 decision that the use of race in admission by the University of Texas was acceptably tailored, strengthening the Bakke precedent. Dissents in this last case contended that race-neutral classifications could, in fact, achieve diversity, and that the objective of enrolling a diverse student body was too tenuously defined to justify race-conscious admission.

In the Fisher II dissent, Justice Samuel Alito Jr. also wrote that “In particular, the Fifth Circuit’s willful blindness to Asian American students is absolutely shameless.”

The ongoing suit against Harvard is comparable to the Texas case because the plaintiffs use similar evidence, according to Backes. “It’s not like they have a slam-dunk case,” he said of Students for Fair Admissions. In addition, Fisher I and Fisher II were orchestrated by the same person and organization bringing the case against Harvard now.

A partisan divide?

Students for Fair Admissions has the mission of ending affirmative action and was established out of the Project on Fair Representation. The president of both organizations, Edward Blum, a Republican, has staunchly and conspicuously opposed race-based classifications both in voting laws and affirmative action.

Another professor characterized the partisan divides as more stark in this case than in others. “This suit is more about protecting spaces for white students than it is about concern for Asian American students,” Moses wrote. “The case absolutely reflects a right-wing agenda.”

“The mission of SFFA is to end racial classifications and preferences in university admissions. We have the broad support of large majority of Americans of all races and ethnicities,” wrote Blum in an email to The Herald, in response to Moses. He referred to a 2016 Gallup poll showing that 70 percent of Americans believe merit should be the only factor in college admission.

While challenges to affirmative action are typically characterized as conservative, the specific complaint of Asian American applicants may mean “conservatives and liberals will come down on both sides on this one,” Brown suggested.

This case “is changing the opinions of a lot of Asian Americans,” said Chang, who noted that Asian Americans usually favor affirmative action. According to the 2012 National Asian American Survey, for example, 76 percent of Asian Americans support affirmative action.

U.S. District Judge Allison Burroughs has scheduled a trial for October 15. The case is widely expected to be appealed to the Supreme Court regardless of the outcome.

ADVERTISEMENT