The votes were in, and the result was outrage. The newly elected Republican administration left many students fearing the nation’s future. To Brown’s liberal student body, the new president looked like a step backwards, a danger to the country, a threat to their values.

Some took this as a call to action. In response to the seismic political shift, student activists mobilized.

This was the scene after 1980. And 2000. And 2016.

In the wake of President Trump’s election, student activists have been reacting to a barrage of controversies and political issues. Though some students feel they are navigating uncharted territory in American politics under the Trump administration, these turbulent waters come in waves. The Herald looked back through its archives to understand how students have reacted to shifting political climates since the 1980s.

Since the 1960s, Brown has been known as a hotbed of activism, but student mobilization has ebbed and flowed throughout the decades.

Read this story another way here

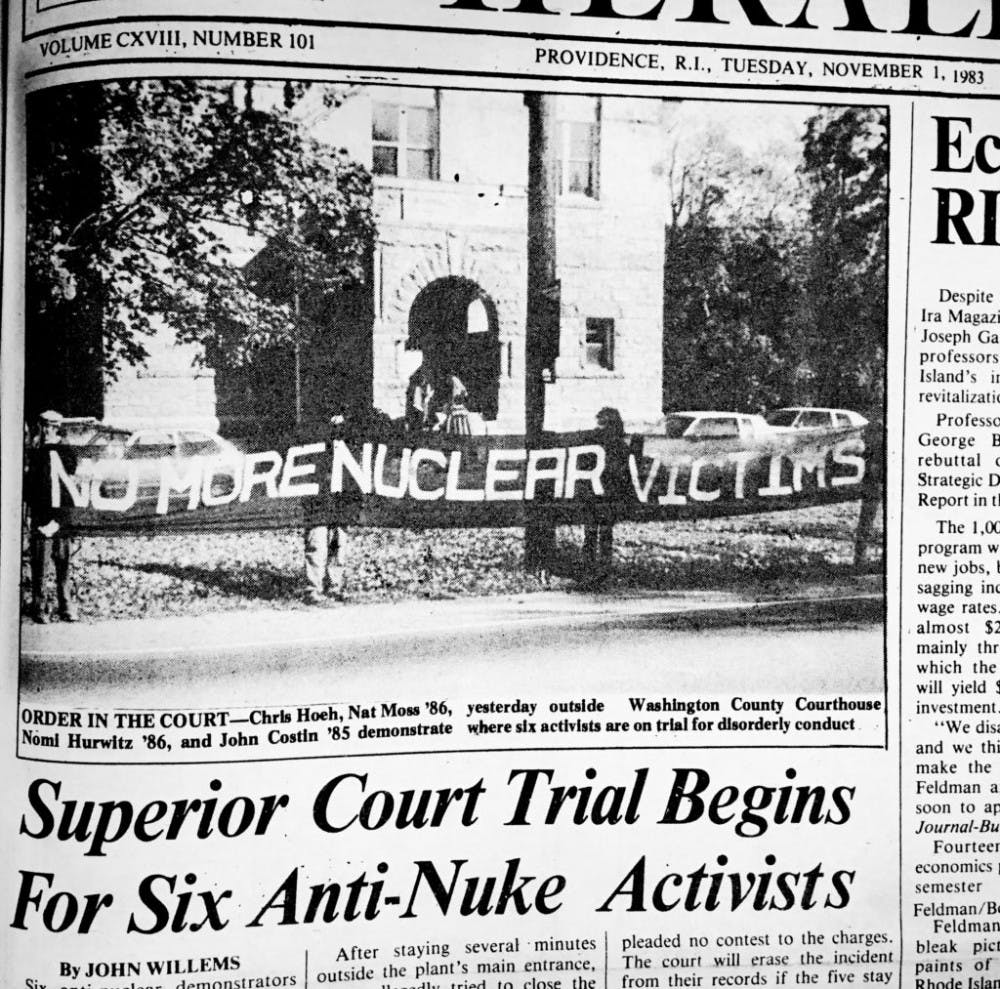

The 1980s saw a flood of political movements that reflected the tumult of the era. Groups like the Brown Free Southern Africa Coalition pushed the Corporation to divest from companies that did business with South Africa. Students Against Nuclear Suicide demonstrated against the proliferation of nuclear weapons. People Against the CIA worked to resist CIA recruitment on campus. Citizens in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador protested American interference in Central America.

Across this alphabet soup of activist movements, students staged a number of high-profile demonstrations, often making headlines in The Herald and, occasionally, the national news.

Looking back on their time as student activists, several alums noted that former President Ronald Reagan’s foreign policy — supporting anti-communist guerilla rebels in Central America, maintaining ties with South Africa’s amidst apartheid, accelerating the nuclear arms race — fueled the fire of their activism.

Reagan’s victory felt like “the end of the world,” said Jason Salzman ’86. “He was exactly the wrong person at the wrong time, especially if you thought the world was going to self-destruct at any moment.”

The resistance gathered. “Buildings were taken over, and people went on hunger strikes,” said Andrew Meyer ’89.

Students who came to Brown during the death throes of the Cold War felt especially threatened by national politics, and their movements developed a sense of urgency, Meyer said.

But by the ’90s, the political climate had calmed. Gregory Cooper ’01, a current high school government teacher, recalls that in the post-Cold War, pre-9/11 era, he felt less of the “sense of urgency with respect to our politics that I think people feel today.”

But the urgency that drove activists in the ’80s has seen a resurgence today, some activists say.

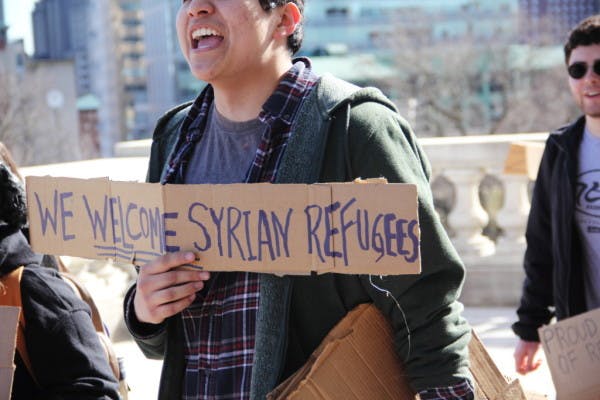

In the last year, students have staged protests against Trump’s threats to Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, his immigration ban, gun violence and Trump’s election itself. But Brown has not seen activism regarding national affairs as pervasive as the movements that swept College Hill in the 1980s.

“There are bigger fires to put out right now than the stuff internal to the campus,” said Emma Galvin ’18.5, an organizer for the Brown Student Labor Alliance. In the last year, Galvin has worked on campaigns for migrant justice, Temporary Protected Status and #DisruptJ20 — a movement to protest Trump’s inauguration.

“There’s been a large resurgence,” Krissia Rivera Perla ’15 MD’21 said, citing medical students’ work to support immigrants and the work of the Brown Immigrant Rights Coalition. “When injustice happens, students will rise up and lead.”

But Trump’s victory demoralized some activists, overwhelming them and dispersing their efforts, Galvin said. As a result, activism at Brown seems to have calmed compared to earlier years, she said.

The 1980s saw a surge in student activism, said Jeremy Varon ’89, a former student activist who now studies the history of social movements. Students then “weren’t so stunned and paralyzed and overwhelmed with rage and shock” as they seem to be in 2016, Varon said, so " it was easier to enter into activism."

[caption id="" align="alignleft" width="417"]

But “every generation thinks that they were more active than the newest generation,” said Scott Warren ’09, who was once arrested for protesting the Darfur genocide. Salzman echoed this sentiment. “The activism is always greener,” he said. During his activist years, Salzman recalls thinking, “Shit, if only we had been at Brown in the ’60s.”

Some alums called the mobilization of the ’80s a product of their ’70s upbringing — a decade rocked by anti-war uprisings and political scandals. “Our childhoods were Vietnam War, Watergate,” said Maria Testa ’86. “We basically hit campus with a degree of mistrust.”

Today, the activism of the 1960s is a much more distant memory. Current students came of age during a far more stable time — the era of former President Barack Obama — than the turbulent political climate that propelled students activists in the 1980s.

“The reality is that young people (today) are really active,” Warren said. “They just take action in different ways.”

Though national and international issues ignite many protests, life on College Hill has similarly been the focus of student activism throughout the years.

“Universities are best when the students are taking on the injustices in the University itself,” Varon added. “If you’re a student, starting in your own neighborhood makes sense.”

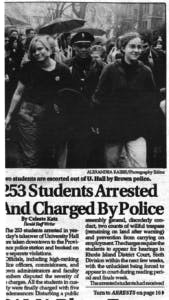

As Reagan’s term neared its end, controversy surrounding sexual assault erupted on campus. Rallies for divestment from South Africa gave way to marches against sexual assault and date rape. Many also fought for a need-blind admission policy, culminating in a takeover of University Hall in 1992 that ended with 253 student activists arrested.

While the activist atmosphere persisted, the focus on geopolitical issues that consumed the campus for much of Reagan’s presidency fell by the wayside.

“I needed something that I could get my head around or feel like I could do something about,” said Naomi Sachs ’92. “For me, global politics just seemed too big and too unwieldy.”

But even when protests are directed toward issues on campus, national and international political issues remain relevant to student activism.

In many cases, students have pushed the University to act in support of political or social causes. The most influential movements “were the ones in which students found ways to connect these larger political issues to the University community in some way,” Salzman said. In 1984, Salzman spearheaded a campaign to stock the University with suicide pills for optional use in the event of a nuclear war.

Other students in the ’80s who opposed American interference in Central America focused on preventing the CIA from recruiting students at Brown. “This was a local struggle on a single campus that, in our minds, was deeply connected to a larger post-Vietnam anti-intervention politics,” Varon said.

Ever since the 1980s movement to divest from companies doing business with South Africa, students have targeted Brown’s investments as a method of linking the University to issues abroad. During the Darfur genocide, students successfully pushed the University to divest from companies doing business in Sudan. Alongside schools nationwide, students encouraged the University to divest from coal companies in 2012 and 2013. More recently, students on campus and around the country have pushed for divestment from Israeli companies.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="650"]

“It was such a huge defeat,” Matzzie said. “For me, at least, it sparked the need for protests outside of the electoral system.”

It’s no coincidence that political activism among students has flared up during administrations that oppose students’ predominantly liberal interests. “Activism felt like the only way to get your voice heard,” Matzzie said. “We’re going to have to organize outside of the system to pressure the system.”

Yet, even under liberal administrations, students’ faith in the system has wavered. David Wade ’97, a student during former President Bill Clinton’s presidency, said students debated “about whether or not traditional politics was worthwhile and whether the two-party system was broken.”

The presidential election of 2000 — when former President George W. Bush won the electoral college but not the popular vote — particularly shook students’ confidence in the electoral system.

Today, faith in the political process seems to have reached a new low. Young people participate less in politics than previous generations, Warren said.

“I don’t trust political processes,” Galvin said. The view isn’t uncommon on campus. Fewer and fewer students seem to believe that government action leads to progressive change.

But not all activists have given up hope in working within the political process. Perla’s immigrant rights group organized a phone bank in December to advocate for the “DREAM Act and to advocate for keeping Temporary Protected Status.” She added that U.S. Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., has backed their work, too.

Some students question whether activism is any more effective at making change happen than working within the system. As a student, John Crouch ’91.5 worked with Brown’s chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union. Though he supported many of the causes promoted by activists, he objected to civil disobedience tactics used by more radical students such as staging die-ins, and chaining themselves to fences. Instead, he found that partnering with the administration produced more results.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="650"]

“To be taken seriously, you need to be at the table, but without the protests and the groundswell, I don’t think we would have gotten to the table,” said Testa. During her time at Brown, she met with Corporation members, urging them to divest from South Africa.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="650"]

“Often you have campaigns targeting the University just because that’s a way for students to use the power that they have,” explained Emily Kirkland '13, a former member of Brown Divest Coal.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="800"]

Whatever the motive, “I rarely got the sense that the administration was trying to intimidate people or disincentivize them from activism,” Meyer said. “It always seemed like they were just trying to get through the moment without anybody getting hurt.”

But the University does not always respond to student activism. In spite of the intense student activism pushing for divestment from South Africa in the 1980s, the Corporation refused. By the time apartheid finally fell, the University still maintained holdings in companies linked to South Africa.

Some students fatigued by activism — by fighting what may feel like losing battles — turn instead to more direct means of making change. “My personal tendency was to move away from activism and move toward actual advocacy, like working in a community,” said Nerissa Wu ’89.

In the face of an overwhelming wave of controversy surrounding sexual assault on campus, Sachs favored a similar approach. “Getting involved with the Sexual Assault Prevention Education program, that was a way to engage in a more positive productive way rather than just feel like I was just banging my head against the wall,” Sachs said.

To many outside of campus, frequent headlines publicizing Main Green rallies can make Brown’s entire student body seem mobilized. But most activists would agree that movements are led by a “small but vocal” group of students, as Galvin put it.

Across several movements, student activists weren’t just a minority — they were also a close-knit group of friends (Brown Divest Coal’s leadership comprised just 10 to 15 students around 2012, Kirkland said.) The challenge student activists face is mobilizing the rest of the student body.

Although Brown’s student body has never been universally liberal, alums generally agreed that most students sympathized with activist causes. But in spite of this broad support, some activist leaders saw many peers as apathetic.

“As an activist, the climate always seems less active than you want,” Salzman said.

Not all alums agreed. “I met very few truly apathetic people,” Daniel Sherrell ’14 said. Instead of apathy, a lack of awareness may have contributed to lulls in student activism. For Perla, in her undergraduate years under the Obama administration, people were generally “more complacent with the administration.”

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

“Most people, students included, go along to get along,” said David Goldsmith ’85. “Their courseloads are full, their exams are worrisome and their primary concerns are doing as well as they can for the thousands and thousands of dollars that they’re paying.”

And while students come out in droves for an afternoon rally, those protests are “a single facet of what it means to do social justice work,” Sherrell explained.

“People will be super down to put on the mask and march in University Hall, and I’m all for it,” Galvin said. “But I think that there also needs to be relationship-building.”

Many former activists compared the work of sustaining a movement to a full-time job, with some working 20 to 50 hours a week. “I don’t remember going to class a lot during these days,” Testa said. How she fit the Brown education in between protests and meetings with the Corporation, Testa can’t recall.

Activist movements thrive on publicity. That’s what demonstrations are for — they’re “meant for public consumption,” Todd Weir ’88 explained.

To attract attention, activists need to be media savvy. “You have to talk in sound bites,” Weir remembered a fellow activist telling him.

But Brown being Brown — an Ivy League institution — students don’t need to try too hard to draw media attention. “We could get eyes and ears on what we were doing, and we used it,” Testa said.

Later, Matzzie coordinated press contacts for another instance of radical activism — a 10-day fast for divestment from South Africa. She called media outlets, letting them know about the students who were refusing to eat after Brown refused to divest. “It was the only way to get your voice heard,” Matzzie said.

But students today face a vastly different media landscape. “There was no such thing as social media,” Matzzie noted. “There was no way to get your voice heard online. ... So pulling people together in a rally, signing petitions, having a hunger strike in Manning Chapel — which got national press — was the way.”

Student activists in the 1980s prided themselves on the creativity and intensity of their demonstrations. “It was all very theatrical,” said Todd Weir ’88, who joined more than 60 students in placing CIA recruiters under citizen’s arrest in 1984.

In another form of performance protest, students have occasionally held die-ins — rallies where scores of students would pretend to be dead on the green — to protest issues like nuclear warfare in the 1980s and the Darfur genocide in 2006.

For a more light-hearted demonstration, the Young Communist League once organized “Dance Dance Revolution,” which assembled over a thousand students for a conga line protest “against the Undergraduate Council of Students, President George W. Bush, his war against Iraq and world order in general,” The Herald reported in 2003.

Students throughout the years have gone so far as getting arrested for demonstrations at places like University Hall, the State House and the White House. “We wanted press attention,” said Warren, who was arrested for protesting the lack of U.S. involvement in the Darfur genocide. “We wanted to demonstrate the extent to which we thought this was urgent and that we would be willing to get arrested.”

[caption id="" align="alignleft" width="300"]

Still, protests remain a crucial part of present-day activist movements, such as Brown Divest Coal. By mobilizing students and reaching out to the press, the campaign to divest from fossil fuels amassed momentum, enough to get featured on NPR.

“Right after that story aired, (President Christina Paxson P’19) sat down with us personally and invited us to present to the Brown Corporation,” Kirkland said. “I learned through working on fossil fuel divestment that it’s not about making the case. It’s about building enough power that you don’t give the administration a choice.”

“The things that were loud and made trouble got covered,” said Wu.

But creative demonstrations and radical tactics aside, the core of organizing hasn’t changed for activist movements over the decades. “Organizing is fancy words for talking to people,” Galvin said.

To spread awareness of Brown Divest Coal, “we did dorm storms, asking people to sign a petition, held rallies, reached out to the press,” Kirkland said. For decades, students involved in activist movements have done these exact same things. And — as the appearance of Brown Divest Coal on NPR in 2013 goes to show — student activists don’t need shocking demonstrations to score national press.

Several former student activists acknowledged that they lost many of their battles. But they still saw their activism as successful in sparking conversation. “We were not successful in the short-term, immediate goal of getting Brown to divest,” said Paul Zimmerman ’88. “But I think in the benefit of hindsight, we were absolutely successful — the student movement, the general anti-apartheid movement — in changing public opinion.”

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="650"]

“They knew who they were admitting. They knew it was a bunch of curious, crazy, precocious rebels. At some level, they were welcoming all the grief that we gave them,” Varon said. “That’s the sense in which my activism feels like a legacy of Brown and not just a legacy of protesting Brown.”