In the first scene of “A Quiet Place,” the new film from actor and director John Krasinski ’01, a family tiptoes around an abandoned general store to gather a few necessities. We hear the soft taps of their bare feet on the linoleum and the slight rattle of pills in a bottle as the mother carefully picks them up. No one speaks, and nothing goes boom. And yet the longer the quiet lingers, the more uneasy we become. It’s an effective opener, putting the audience on edge as they wait for a pin to drop. But it also puts into stark relief what is maybe an obvious realization: Most movies are awfully loud, aren’t they?

The decibel count eventually goes up in “A Quiet Place,” and the movie becomes significantly less interesting when it does. But for a few brief stretches, the film uses silence in a way that sets it apart from most movies of its ilk. The quieter something is, the closer we listen, and “A Quiet Place” occasionally takes this lesson to heart, using it to craft some delicious scares and to deploy tension with admirable finesse. Had Krasinski been more ruthless in sticking to his premise, the film might have been a real nerve-jangling knockout. But as it stands, “A Quiet Place” is decent, scary fun.

The story unfolds in a world ravaged by nonhuman predatory creatures. Gifted with extremely sensitive hearing, they hunt and kill anything within earshot with quick, violent efficiency. The stakes are viscerally established at the beginning of the film when a child, Beau, is snatched up mere seconds after his electric rocketship toy makes noise.

Beau’s death will haunt his parents, Lee (Krasinski) and Evelyn (Emily Blunt), and their other two children, Regan (Millicent Simmonds) and Marcus (Noah Jupe), for the rest of the film. The four of them live in a country farmhouse surrounded by rows of corn, where they’ve created a viable but always precarious lifestyle amongst the world’s new order of violence. Sand muffles the sound of footsteps on the paths around the property, paint circles mark the floorboards that creak the least, and leaves replace plates to prevent dinnertime clanking. And, of course, the family almost never speaks aloud to each other, instead communicating through American Sign Language.

But they persist. Perhaps the most obvious sign of their optimism is the fact that Evelyn is pregnant, although this comes across as a little more delusional than Krasinski may have intended. Babies are great, but not exactly silent, and the solution the film proposes to this is patently absurd. So is most of the stuff in this movie, as a matter of fact, but nobody likes a pragmatic scold, and I don’t intend to be one.

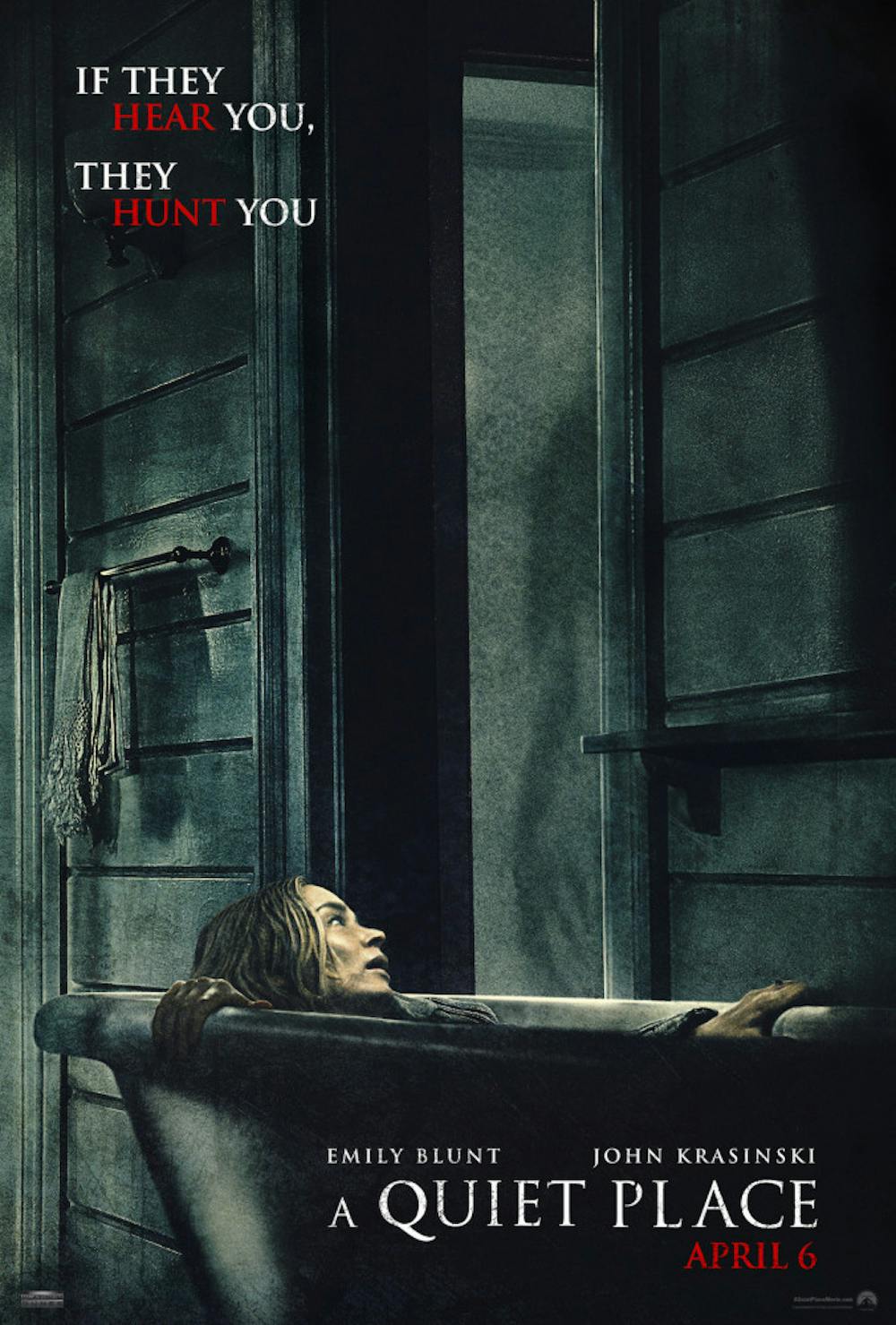

Nothing particularly scary happens for much of the film — we watch the family merely live their lives and act out some dull smudges of emotional drama. The cast, at least, is good, including Blunt — married to Krasinski in real life — and Simmonds, a deaf actress who, between this and last year’s “Wonderstruck,” is shaping up to be one of the most talented young actors in Hollywood. And everything is nicely accented by the fluid cinematography of Charlotte Bruus Christensen.

But at least one scene amidst the film’s more sedate first half really sticks with you: As Lee and Marcus walk back to the farm from a fishing expedition, they come across an old man standing by his wife’s bloody corpse. His face is troubled, his lips curled inward. Just as they start to run, the old man lets loose a mournful scream. In seconds, he is killed. In this world, to scream is to die; to express pain is to be ended by it.

The motif of the scream returns twice more throughout the film, and both moments are among the film’s best. But too much in between lacks urgency or invention. An expert set piece turns into a bloated latter half of a film, story beats are repeated and cheap jump scares crop up like cornstalks in the springtime. Meanwhile, excess noise starts to seep into the film’s meticulous soundscape, from Marco Beltrami’s score to the smorgasbord of overused sound effects. Krasinski spends a lot of his time shushing people in this movie; it’s a shame the same impulse didn’t make it into his direction.

As it nears its end, “A Quiet Place” grasps around for a conclusion for a while without ever really finding one, eventually coming to a defiant halt that only works if you don’t think about it for too long. And maybe you shouldn’t. All I know is when the last shot cut to black, the audience clapped and I took my hand away from eyes and said “what’d you think?” to the person next to me, it felt good to speak again.