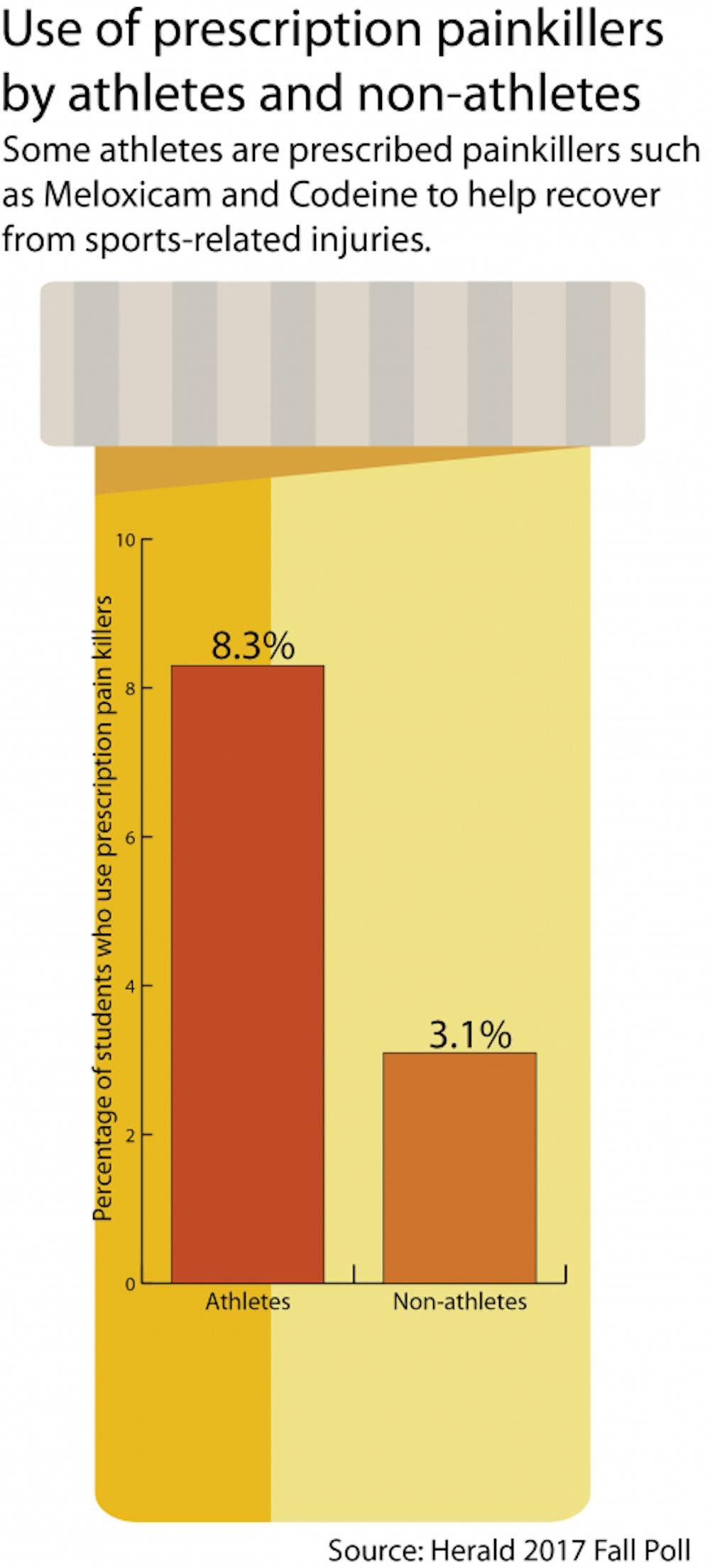

Varsity athletes use prescription painkillers nearly 3 times more than non-athletes, according to The Herald’s fall 2017 poll. While 3.1 percent of non-athletes reported using painkillers recreationally, 8.3 percent of polled athletes reported that they do.

Researchers said athletes — who may overuse painkillers to cope with pressure to perform at high levels — could be at greater risk for painkiller abuse than non-athletes due to their increased access to prescriptions.

Multiple varsity athletes responded via email that they were not aware of recreational use of these drugs among their teammates but mentioned that, in the case of injury, athletic trainers can provide such prescriptions.

Recently, the Trump administration declared the opioid crisis a national health emergency but did not allocate any funding to deal with the issue. Between 2005 and 2015, opioid-related deaths among Americans age 24 and under almost doubled, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Opioid-related emergency room visits by young people also nearly doubled over five years, according to the United States Department of Health and Human Services.

Though “painkiller” can be used to mean drugs such as Ibuprofen and Tylenol, these pain relievers function by reducing fever and inflammation. Painkillers, on the other hand, include powerful opioids such as Hydrocodone and Oxycodone. When used for non-medical purposes, painkillers can create a “high” similar to that of other opioids, such as heroin.

According to an NCAA study, student-athletes are prescribed narcotics for pain medications at higher rates than other students. And in a recent New York Times article, one researcher pointed out that athletes in high-contact sports, such as ice hockey or wrestling, are often prescribed these medications and can be especially vulnerable.

The men’s lacrosse, women’s ice hockey, wrestling and volleyball teams did not respond to requests for comment.

“From what I know about painkillers, they are mainly prescribed by either team or personal physicians in response to injuries,” wrote Richard “Dewey” Jarvis ’17.5, co-captain of the football team, in an email to The Herald. “But most of the painkillers that we are prescribed do not have narcotic effects.”

Generally, Brown coaches discourage the use of painkillers among their teams, even for medical purposes.

Sara Carver-Milne, head coach of the gymnastics team, said she encourages team members to listen to their bodies and openly discuss their health.

“We do not in any way recommend that they use painkillers,” she said. “We have them see our trainer before and after every practice to ensure that they’re taken care of and ensure that they’re taking the steps necessary to be healthy.”

Of the student-athletes contacted by The Herald, few mentioned specific painkillers, but some said they had been prescribed Meloxicam (commonly referred to as Mobic), a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, and Codeine, an opioid.

Erika Steeves ’19 and Megan Reilly ’18, co-captains of the women’s basketball team, wrote in an email to The Herald that they had been prescribed both these drugs to aid with injury recovery.

“While we didn’t necessarily use them, they’re still in our possession,” they wrote. “Once we don’t need them anymore, we have to give them to our trainer, but I don’t think the same can be said for every sport.”

Opioids or not, painkillers can still be dangerous for athletes in developing drug dependencies, a fact that athletes, coaches and professionals alike are aware of, at both the collegiate and professional level.

Philip Veliz, research assistant professor at the Institute for Research on Women & Gender at the University of Michigan, said athletes may use prescription painkillers to “mask pain in order for them to participate” in their sport.

“If they do have a really nagging injury and they don’t want to sit out, they may be using those (substances) so they can continue to participate,” he said. “They might have the mentality that they’re going to do whatever it takes in order to get back on the playing field and perform at an optimal level.”

After performing with the aid of these substances for an extended period of time, athletes might believe they must continue using these drugs to maintain the same level of performance.

For college athletes in particular, Veliz said, “your identity really hinges on this idea of being a confident athlete. If you can’t maintain that, you’re going to have this anxiety that you’re going to lose your friends or your close relationships.”

“Athletes may have more internalized pressure to … self-medicate in order to perform,” he added.

Bryan Denham, chair of the communication department within the College of Behavioral, Social and Health Science at Clemson University, said “sensation seekers” may be more prone to shift from using painkillers as performance enhancers to recreational pleasure.

“Sensation seekers tend to be a bit more willing to experiment with drugs,” he said. “They often are injured and need a pain reliever, but sometimes that sense of well-being is too much to resist, and they continue with using these drugs.”

Kenneth Leonard, director of the Research Institute on Addictions at The State University of New York at Buffalo, echoed Denham’s sentiment in an email to The Herald. “I would imagine that there are a fair number of athletes who are high risk-takers, and, perhaps, this risk-taking also involves substances.”

Sometimes the choice to misuse these substances is not even for thrill-seeking, but simply to feel better. Jeremiah Gardner, manager of the Hazelden Betty Ford Institute for Recovery Advocacy who is himself in long-time recovery, said that those who are inclined to use other substances recreationally might be more at risk for using painkillers that way if they’ve been exposed to them.

“If you’re a student who is inclined to drink or perhaps use marijuana, if you’ve used opioids for medical reasons and experienced the feeling that comes with that, it no longer is a stretch to think you might use those for recreational purposes,” he said.

The Herald’s poll found that 87 percent of athletes drink alcohol, whereas 80 percent of non-athletes do so. Rates of marijuana use were the same for each group — around half have used it in the last year.

Moreover, “as a group, they may have easier access, particularly if they have had their own prescription, or a teammate’s prescription,” Leonard wrote.

Over-prescribing can also enable abuse problems. “You don’t need to have a supply of 30 opioids or 30 pills to deal with an injury,” Veliz said. For example, if an athlete requires knee surgery, they need no more than two or three pills, adding that “the rest can be Tylenol.”