LGBTQ+ applicants may need to decide whether or not to come out to potential employers before having gauged the inclusivity of a particular workplace.

“I was advised not to disclose my identity,” wrote Jennifer Nykiel ’10 MD’14 in an email to the Herald. “I was told it would limit my options.”

Instead, she only applied to programs in liberal regions and “disclosed everything.”

“I wouldn’t want to work somewhere I had to be in the closet,” she wrote.

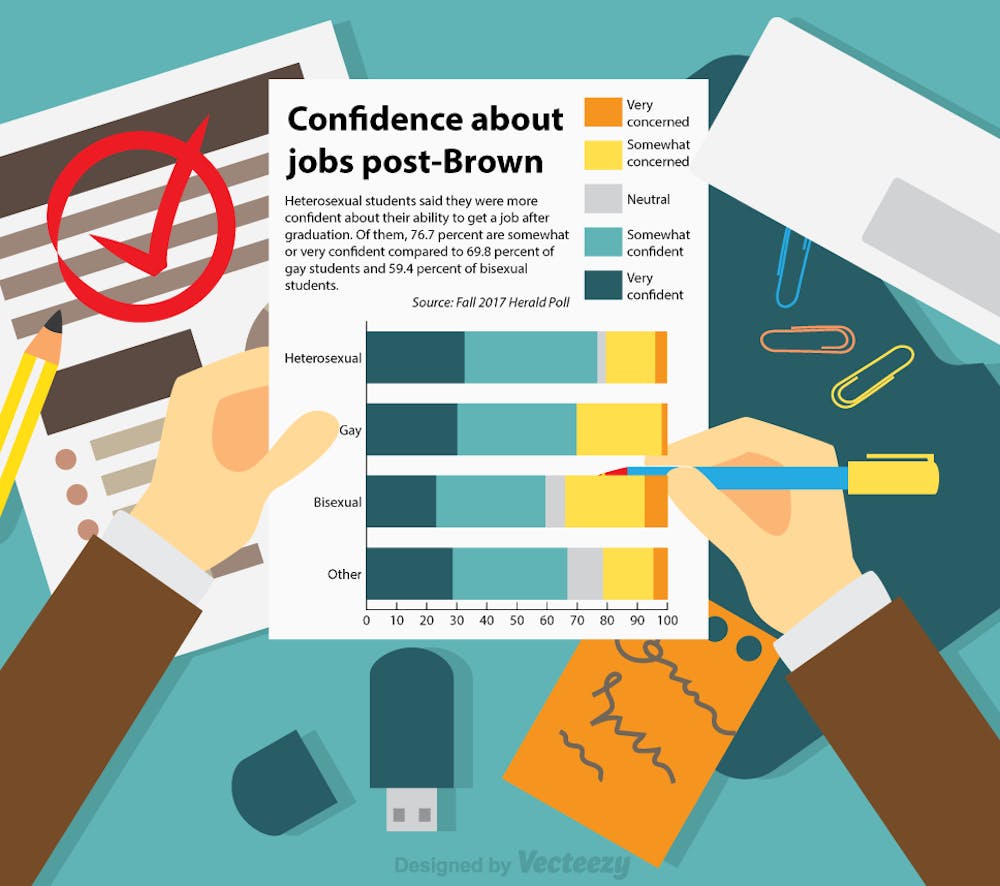

Students who identify as gay, bisexual or other report less confidence in their ability to secure a job in their chosen field than heterosexual students, according to the Fall 2017 Herald poll. Of heterosexual students, 76.6 percent indicated feeling somewhat or very confident in regards to job placement in their chosen field post-graduation, while only 65.3 percent of those gay, bisexual or other students shared this sentiment. One in five of those surveyed by the Herald identified as LGBTQ+.

LGBTQ+ alums cited challenges they faced in the workplace, including navigating the interview and hiring process, the average workday and particularly heteronormative industries.

Issues that LGBTQ+ people encounter may be complicated by the current political climate. Nationally, 28 states lack employment anti-discrimination laws regarding sexual orientation or gender identity. And recently, the Justice Department filed court papers arguing the Civil Rights Act does not protect employees from discrimination based on their sexual orientation.

While some employers have made symbolic nondiscriminatory policies to protect those with LGBTQ+ identities, they lack the formal power that a state or federal law would hold.

When it comes to applying, submitting a resume is a challenge itself. The decision to include certain clubs or organizations — such as the Queer Alliance — can out applicants. At his previous job, CareerLAB Director Matthew Donato was asked by a trans male student if he should list his most extensive community service experience: his work with Girl Scouts of the USA.

“I said … if you’re really worried about how an employer is going to react to that, that may not be the type of employer that you want,” Donato said. While that may not be the right answer for everyone, “it’s things like that, like ‘Do I disclose my participation in this club or this group on campus?’”

These concerns are not unfounded. Studies have found that the resume of a heterosexual person is more likely to advance to the next stage of the hiring process than the same resume of someone who disclosed they were gay through clubs they listed.

Gregory Cooper '01 included his work with Gay-Straight Alliance and the LGBTQ+ community to signal to future employers that he valued an inclusive workplace. Flavio Casoy ’03 MD’09 did the same, including his involvement in LGBTQ+ groups to ensure employers who reached out to him knew his sexual orientation.

Donato said asking about sexual identity in an interview is illegal and would not be tolerated by CareerLAB. “If a student finds out or tells us about an employer that’s discriminating against them or conducting illegal interview questions, … we are pretty aggressive about sidelining an employer,” Donato said. But he noted that he has not had to do that for discriminatory reasons since he started as director.

Still, some alums said they had to make decisions about whether to be overt about their sexuality when meeting an employer for the first time.

Before applying for residency, Casoy discussed with his fellow LGBTQ+ medical school peers whether to come out as gay during the interview.

“After a lot of deliberation, we decided it was best to be public and somehow let drop in the interview that you were gay or bi or lesbian or trans,” he said. That way, he would not risk ending up in a workplace that was overtly homophobic, he said.

Matthew Laderer ’03, who has been comfortably out at his current job as a project engineer for years now, said he aimed to appear more traditionally masculine in job interviews upon first entering the workfield.

“I can be very animated. I wear my emotions on my sleeve,” Laderer said. “I was not even really thinking about not being effeminate. I just wanted to come off as being professional.”

Some alums said they also tried to avoid applying to graduate programs that were widely known to be homophobic.

And once they’ve been hired, some LGBTQ+ people feel like they need to hide their sexual orientation in fear of discrimination or disapproval from coworkers, said Christy Mallory, a lawyer who studies issues that impact LGBTQ+ people at the Williams Institute.

Mallory’s own research, conducted from a national survey, found that a quarter of lesbian, gay or bisexual employees had experienced harassment at work. Several Brown alums said they, too, had been discriminated against in the workplace or in graduate school.

During his rotation under a pediatric endocrinologist, Casoy’s instructor found out he was gay and stopped assigning him patients.

“Both (my partner) and I experienced homophobia in medical school,” Casoy said. “I didn’t learn for a brief rotation because I didn’t see anyone.”

Many alums also mentioned varying levels of acceptance depending on the industry or workplace culture.

“The widespread homophobia that prevailed on Wall Street in the 1970s through 1990s has largely disappeared and been replaced by a progressive attitude that diversity is better for performance,” wrote Mike Balaban ’74 in an email to The Herald. He was in the closet for the duration of his career on Wall Street. “That doesn’t mean that individuals within those firms might not harbor homophobic attitudes, much like they might hide racist and sexist views, too,” he noted.

And certain industries — such as finance and tech — are known to be very male-dominated spaces, which often inhibits queer voices, said David Owen ’08.

An article by Fortune found that 80 percent of high ranking officials at Fortunate 500 Companies are men and that 72 percent of those men are white.

But he noted that these companies have also made efforts to create affinity groups to attract talent from a variety of underrepresented groups.

Owen has worked in small arts organizations and with the City of New York. Between the two, he noted that “government tends to be more conservative in terms of dress, manner (and) professionalism.” In addition, Owen marked the difference in atmospheres between a large organization and a small one, where LGBTQ+ individuals might be able to share more about themselves.

Those who don’t speak up may be assumed to be cisgender or straight, he said.

“For queer people, that can sometimes feel like erasure of identity,” Owen added.

Adam Brown ’06 works in the performing arts and said he has found those workplaces to be progressive and accepting. But he has performed as a paid member of a Catholic church choir, where he felt an intense amount of pressure to monitor the way he presents himself.

“I’m always second guessing how I’m behaving,” Brown said. “I also question the motives and intentions of people who are even saying something very nice to me, and whether that is … conditional. Is that something they’re only saying to me because they think I’m straight, or I haven’t told them I’m gay? Would they be saying the same thing to me if they knew?”

Currently, Brown provides career help to LGBTQ+ identifying students. The CareerLAB will host its second LGBTQ+ CareerCon Feb. 10, 2018, and the Renn Mentoring Program will induct its newest LGBTQ+ Brown faculty mentor and undergraduate mentee pairs this coming week. Donato hopes CareerLAB staff will undergo training to equip them with the best “language” when assisting LGBTQ+ students.

This article was updated Jan. 28 at 4:45 p.m. to include the date for the 2018 LGBTQ+ CareerCon.